This report describes the results of the analysis of pacemaker implant and replacement data submitted to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2014, with special reference to pacing mode selection.

MethodsThe report is based on the processing of information provided by the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card.

ResultsInformation was received from 117 hospitals, with a total of 12 358 cards, representing 34% of estimated activity. Use of conventional generators and resynchronization devices was 784 and 64.4 units per million population, respectively. The mean age of patients receiving an implant was 77.3 years. Men received 59% of implants and 56.4% of replacements. Most patients receiving generator implants and replacements were in the age range 80 to 89 years. Most endocardial leads used were bipolar, and 84.2% had an active fixation system. Pacing was in VVI/R mode despite being in sinus rhythm in 24.7% of patients with sick sinus syndrome and 24% of those with atrioventricular block.

ConclusionsThe use of pacemaker generators and resynchronization devices per million population continued to increase. Most implanted leads had active fixation and approximately 20% had magnetic resonance imaging protection. Age and sex directly influenced pacing mode selection, which could have been improved in more than 20% of cases.

Keywords

The first official report of the Spanish Pacemaker Registry (SPR) (Registro Español de Marcapasos) was published in 1997,1 although the first data were obtained using a survey in 1989.2 Since then, an annual report has been published, which aims to describe the cardiac pacemaker procedures performed in Spain.3–14 The present report refers to activity from the year 2014. It allows publication of the current clinical practice carried out in Spanish hospitals, the appropriateness of this activity in line with current clinical guidelines,15,16 the evolving trends in interventions in recent years, and comparison with the activity of other European countries.17–19 The web site of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Pacing allows publication of most of the annual information provided by the SPR for the period 1999 to 2011,20 although some information might be unavailable due to changes over time (expansions and/or updates).

METHODSThe SPR has 3 information sources: the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card (EPPIC), information provided by manufacturers, and census data supplied by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics.

European Pacemaker Patient Identification CardThe EPPIC for each patient, completed by the participating hospitals, includes an automatically-generated copy that is sent to the SPR. This allows the SPR to use the information it contains: sex, age, etiology, symptoms, electrocardiographic indications, pacing mode, type of generator and electrodes, and date of implantation of each component. The information can also be sent electronically from the hospital databases, provided they contain the data required on the EPPIC. The Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Pacing is currently developing a database for automatic information collection and processing, which will require compulsory completion for each patient to obtain an EPPIC. It is expected that by 2016, this will be the method of choice for sending data, as it is already available.

Information From the ManufacturersDespite current legislation on monitoring of possible alerts (Royal Decree 1616/2009, dated 26 October, which regulates active implantable medical devices), not 100% of EPPICs were sent. Therefore, the data on the number of implanted devices and the distribution by autonomous community was provided by the manufacturers. This information was also sent periodically to the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations (EUCOMED).

Report From the Spanish National Institute of StatisticsThe population figures for calculations related to devices, at both a national level and for the autonomous communities, were obtained from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics updated and published report for the year 2014.21

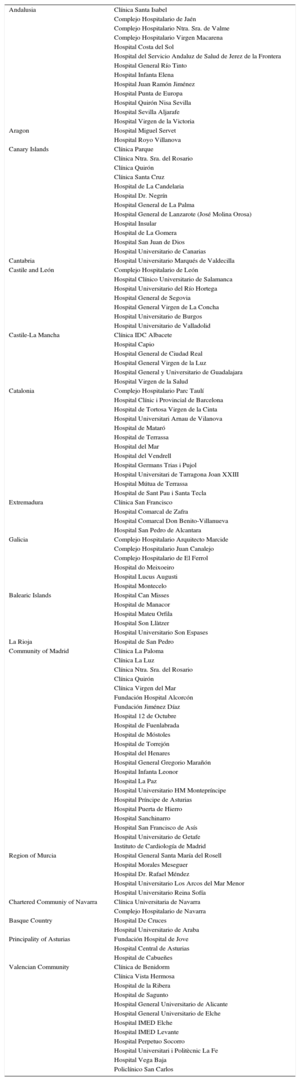

Sample AnalyzedThe data reported are based on information sent from the 117 participating hospitals in this report (Table) and represent 34% of generators used. This sample is considered representative of the cardiac pacing activity carried out in Spain.

The Public and Private Hospitals That Submitted Data to the 2014 Pacemaker Registry, Grouped by Autonomous Community

| Andalusia | Clínica Santa Isabel |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén | |

| Complejo Hospitalario Ntra. Sra. de Valme | |

| Complejo Hospitalario Virgen Macarena | |

| Hospital Costa del Sol | |

| Hospital del Servicio Andaluz de Salud de Jerez de la Frontera | |

| Hospital General Río Tinto | |

| Hospital Infanta Elena | |

| Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez | |

| Hospital Punta de Europa | |

| Hospital Quirón Nisa Sevilla | |

| Hospital Sevilla Aljarafe | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Victoria | |

| Aragon | Hospital Miguel Servet |

| Hospital Royo Villanova | |

| Canary Islands | Clínica Parque |

| Clínica Ntra. Sra. del Rosario | |

| Clínica Quirón | |

| Clínica Santa Cruz | |

| Hospital de La Candelaria | |

| Hospital Dr. Negrín | |

| Hospital General de La Palma | |

| Hospital General de Lanzarote (José Molina Orosa) | |

| Hospital Insular | |

| Hospital de La Gomera | |

| Hospital San Juan de Dios | |

| Hospital Universitario de Canarias | |

| Cantabria | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla |

| Castile and León | Complejo Hospitalario de León |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca | |

| Hospital Universitario del Río Hortega | |

| Hospital General de Segovia | |

| Hospital General Virgen de La Concha | |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos | |

| Hospital Universitario de Valladolid | |

| Castile-La Mancha | Clínica IDC Albacete |

| Hospital Capio | |

| Hospital General de Ciudad Real | |

| Hospital General Virgen de la Luz | |

| Hospital General y Universitario de Guadalajara | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Salud | |

| Catalonia | Complejo Hospitalario Parc Taulí |

| Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona | |

| Hospital de Tortosa Virgen de la Cinta | |

| Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova | |

| Hospital de Mataró | |

| Hospital de Terrassa | |

| Hospital del Mar | |

| Hospital del Vendrell | |

| Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol | |

| Hospital Universitari de Tarragona Joan XXIII | |

| Hospital Mútua de Terrassa | |

| Hospital de Sant Pau i Santa Tecla | |

| Extremadura | Clínica San Francisco |

| Hospital Comarcal de Zafra | |

| Hospital Comarcal Don Benito-Villanueva | |

| Hospital San Pedro de Alcantara | |

| Galicia | Complejo Hospitalario Arquitecto Marcide |

| Complejo Hospitalario Juan Canalejo | |

| Complejo Hospitalario de El Ferrol | |

| Hospital do Meixoeiro | |

| Hospital Lucus Augusti | |

| Hospital Montecelo | |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Can Misses |

| Hospital de Manacor | |

| Hospital Mateu Orfila | |

| Hospital Son Llàtzer | |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases | |

| La Rioja | Hospital de San Pedro |

| Community of Madrid | Clínica La Paloma |

| Clínica La Luz | |

| Clínica Ntra. Sra. del Rosario | |

| Clínica Quirón | |

| Clínica Virgen del Mar | |

| Fundación Hospital Alcorcón | |

| Fundación Jiménez Díaz | |

| Hospital 12 de Octubre | |

| Hospital de Fuenlabrada | |

| Hospital de Móstoles | |

| Hospital de Torrejón | |

| Hospital del Henares | |

| Hospital General Gregorio Marañón | |

| Hospital Infanta Leonor | |

| Hospital La Paz | |

| Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe | |

| Hospital Príncipe de Asturias | |

| Hospital Puerta de Hierro | |

| Hospital Sanchinarro | |

| Hospital San Francisco de Asís | |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | |

| Instituto de Cardiología de Madrid | |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital General Santa María del Rosell |

| Hospital Morales Meseguer | |

| Hospital Dr. Rafael Méndez | |

| Hospital Universitario Los Arcos del Mar Menor | |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía | |

| Chartered Communiy of Navarra | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra | |

| Basque Country | Hospital De Cruces |

| Hospital Universitario de Araba | |

| Principality of Asturias | Fundación Hospital de Jove |

| Hospital Central de Asturias | |

| Hospital de Cabueñes | |

| Valencian Community | Clínica de Benidorm |

| Clínica Vista Hermosa | |

| Hospital de la Ribera | |

| Hospital de Sagunto | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Alicante | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | |

| Hospital IMED Elche | |

| Hospital IMED Levante | |

| Hospital Perpetuo Socorro | |

| Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe | |

| Hospital Vega Baja | |

| Policlínico San Carlos |

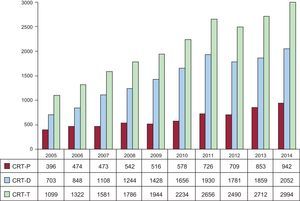

The number of generators registered by the National Pacemaker Bank was 12 358 units, corresponding to the 117 participating hospitals. According to the data provided by manufacturers, in 2014, 36 441 pacemakers were implanted, of which 960 were biventricular pacemakers for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) without defibrillation capacity, or low-energy devices (CRT-P). The total number of cardiac resynchronization devices implanted (CRT-T), including CRT with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (CRT-D), was 3029. The total number of devices reported by EUCOMED was slightly lower: 336 332, with 942 CRT-P pacemakers. Compared with 2013, the total number of implants increased by 1.1%.

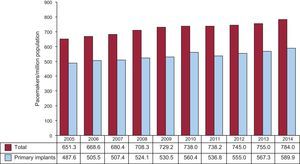

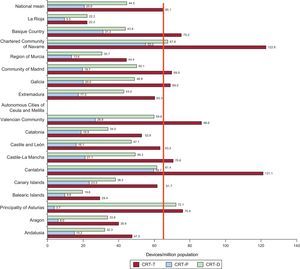

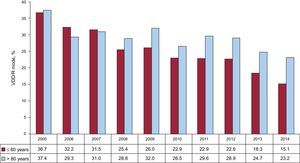

According to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (most recent census data), the population figure at 1 July 2014 was 46 512 199 (22 877 461 males and 23 634 738 females), a reduction of 215 691 people compared with January 2013. According to SPR data, 784 pacemaker generators were used per million population, of which 589.9 units/million corresponded to primary implants (Figure 1). According to EUCOMED, 781 units/million population were used, a figure below the average of the countries providing data to EUCOMED (944 units/million),18 but above other countries with higher per capita income such as the United Kingdom, Norway, and the Netherlands (700, 735, and 728 units/million, respectively).

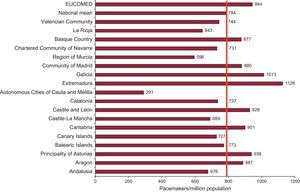

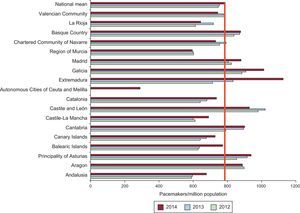

As in previous years, differences between autonomous communities persisted. The number of implants per million population was clearly highest in communities such as Extremadura and Galicia, with more than 1000 units implanted, followed by the Principality of Asturias, Castile and León, and Cantabria, with more than 900 units. This difference is attributable to a higher mean age in these communities (Figures 2 and 3).

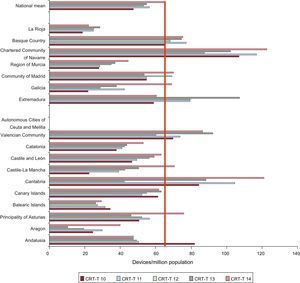

The rate of CRT pacemakers implanted, including low and high energy (CRT-P and CRT-D), was 65.2 devices per million population according to SPR data and was 64.4 units/million according to EUCOMED. This reflects an increase of 10.4% in the total number of CRT devices compared with 2013 data and a further increase in the trend seen in recent years (Figure 4). According to the SPR, 20.3 units/million population CRT-Ps were implanted, a figure well below the mean of the countries sending data to EUCOMED (41 unit/million), thus making Spain one of the European countries with the fewest implanted CRT units /million.17–19

There were also regional differences in CRT pacemaker implantation. The Chartered Community of Navarre and Cantabria implanted the highest number, with more than 120 devices per million population, followed by the Valencian Community, the Basque Country, and the Principality of Asturias. Despite the increase in the total number of pacing devices, Extremadura had fewer CRT-T implants (60.3 units/million population) than the previous year, due mainly to fewer high energy resynchronization implants, which were reduced to almost half. Figures 5 and 6 show the data on CRT-T figures by community, with and without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and the data for recent years.

The mean age of all patients undergoing intervention was 77.5 years (77.3 years for primary implants and somewhat older for replacements at 78.1 years). The mean age differed slightly depending on sex: 76.8 years for men and 78.4 years for women. The highest percentage of implants, the same as the year before, was in the age range 80 to 89 years (42.5%), followed by 70 to 79 years (33.2%), 60 to 69 years (11.9%), and 90 to 99 years (6.5%). Regarding replacements, there was also a higher percentage in the age range 80 to 89 years (44.2%), followed by the ranges 70 to 79 years (28.1%), 60 to 69 years (10.5%), and 90 to 99 years (10.1%). Patients older than 100 years received 0.1% of implants and 0.3% of replacements.

More implants were performed in men than in women (58.3% vs 41.7%), for both primary implants (59% vs 41%) and replacements (56.4% vs 43.6%).

Generator Implants and ReplacementsPrimary implants comprised 75.2% of all activity, at 589 units/million population, an increase of 22 units compared with 2013. Replacements comprised 24.8%, including electrode replacements, which comprised 1.1% of all activity, a figure somewhat lower than that of the previous year.14

The most common reason for generator replacement was battery depletion (90.2%), followed in order of frequency by elective replacement (3.3%), infection-erosion of the generator pocket (2.8%), electrode-related complications (0.8%), change of pacing system (0.6%), and premature battery depletion (0.5%) due to either high thresholds or shorter than expected battery duration. System infection was the reason for replacement in 1.7%, similar to the previous year.

Pacing LeadsPolarityBipolar electrodes comprised 99.7% of implanted electrodes, accounting for 99.8% of electrodes implanted in the atrium and for the same percentage of those implanted in the right ventricle. Most of the unipolar leads (58%) were intended for epicardial pacing of the left ventricle via the coronary sinus and, less frequently, epicardial pacing of the right ventricle (32%) and right atrium (10%) in cardiac surgery. Of the electrodes implanted in the coronary sinus, 65.9% were unipolar.

Lead Fixation SystemsThe trend seen in recent years3–14 continued, with increased use of active fixation electrodes (with a helix system that is embedded in the myocardium and confers stability), making up 84.2% of the total (Figure 7). Although more of these electrodes were implanted in the atrium than in the ventricle, in 2014 this difference was smaller than in previous years (87.6% in right atrium and 82.5% in right ventricle). The preference for this type of fixation was independent of age (85.5% in patients younger than 80 years and 81.9% in those older than 80 years).

Magnetic Resonance CompatibilityCompared with previous years, there was no change in the percentage use of MRI-conditional leads, specially designed for the prevention of possible disturbances during magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging could be performed in a controlled environment in 21.3% of all implanted leads (19.5% of atrial leads and 21.1% of right ventricular leads).

Electrode Replacement and RemovalRemoval of 161 electrodes was required (1.61% of all implanted leads). The main reason was infection or ulceration of electrodes (59.1%), followed by insulation defects (13.6%), elective lead replacement (9.1%), and conductor fracture (4.6%). The remainder (13.6%) were replaced for unspecified reasons.

New electrode implants comprised 1.3% of all activity. Most (1.1%) were performed in the context of generator replacement to improve hemodynamics or achieve a more physiological pacing mode (upgrade). Lead-only replacement was performed in 0.2% of cases.

Symptoms, Etiology, and Electrocardiographic Changes Prior to ImplantSymptomsAs in previous years,3–14 the most common symptom leading to device implant was syncope (42.2%), followed by dizziness (25.3%), dyspnea (15.6%), and bradycardia (10.8%). Less common clinical indications were tachycardia (1.2%), chest pain (1%), cerebral dysfunction (0.8%), and cardiac arrest due to bradyarrhythmia (0.2%). There were no symptoms in 2.7% of patients. In the remaining patients, clinical symptoms were not specified.

EtiologyIn 2014, the most common reasons for implant remained conduction system fibrosis (45.2%) and unknown etiology (39.1%), although probably both etiologies could be included in the same group, as the first is a diagnosis of exclusion. These were followed in order of frequency by ischemic causes (5.1%; after infarct, 0.2%), valvular (3.2%), iatrogenic-therapeutic (3.2%; after atrioventricular node ablation, 0.8%), cardiomyopathy (2.9%; hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 0.5%), and, to a lesser extent, congenital causes (0.7%), carotid sinus syndrome (0.4%), vasovagal syncope (0.4%), and transplant (0.1%).

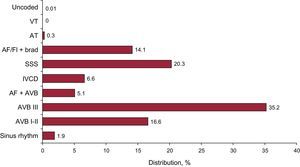

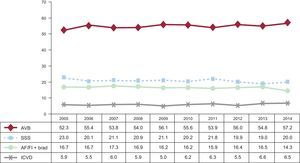

Electrocardiographic ChangesAtrioventricular block (AVB) remained the main electrocardiographic abnormality prior to implant (56.9%), including third degree AVB (35.2%), first and second degree AVB (16.6%), and atrial fibrillation (AF) with complete AVB (5.1%). The second most common electrocardiographic indication was sick sinus syndrome (SSS) in its various manifestations (20.3%), excluding slow AF (14.1%). The distribution of electrocardiographic abnormalities and changes over recent years are shown in Figures 8 and 9.

Electrocardiographic abnormalities prior to implantation. AF+AVB, atrial fibrillation with atrioventricular block; AF/Fl+brad, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter with bradycardia; AVB, atrioventricular block; AT, atrial tachycardia; IVCD, intraventricular conduction defect; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

As in previous years, there was a higher incidence in men than in women of intraventricular conduction defect, AVB, and AF/atrial flutter with AVB or bradycardia (male: female ratios, 2.5, 1.6, and 1.5, respectively). The incidence of SSS was similar in both sexes (male:female ratio, 0.9).

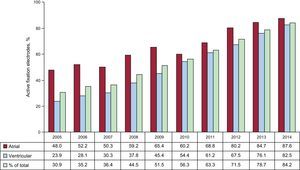

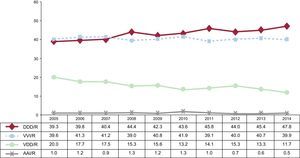

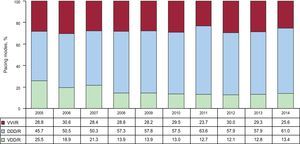

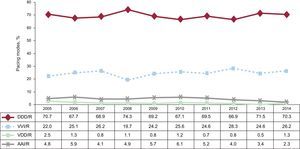

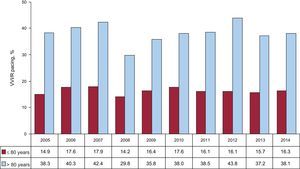

Pacing ModesSingle-chamber pacing comprised 40% of all implanted generators in 2014. This percentage atrial pacing (AAI/R), which, as in recent years, continued to decrease, comprising 0.5% (Figure 10). This decrease was particularly manifest in primary implants, in which this pacing mode has become practically anecdotal (0.3%), moving progressively toward generator replacements (1.1%). Meanwhile, single-chamber ventricular pacing (VVI/R) comprised 39.9% of all implanted generators (41% of primary implants and 36.6% of replacements), data comparable to those obtained in recent years (Figure 10). Regarding electrocardiographic diagnosis prior to implantation, patients with permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia comprised just 19.4% of implants (20% of primary implants and 17.3% of replacements). Therefore, it can be estimated that around 20% of patients receiving single-chamber ventricular pacing could have received a pacemaker capable of preserving atrioventricular synchrony.15,16 However, various factors can lead to the final decision on pacing mode and they are analyzed in the section below, dedicated to pacing mode selection.

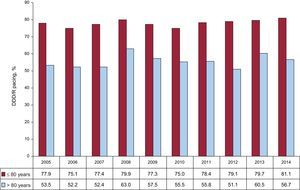

Dual-chamber sequential pacing, using either 1 or 2 leads, comprised 57.9% of all implanted generators. This figure was stable compared with previous years. Single-lead sequential pacing (VDD/R) was used even less than the previous year (11.7% of all units used), confirming the clear decreasing trend observed in recent years (Figure 10). As occurred with AAI/R mode, there was a trend toward less frequent use of single-lead sequential pacing. This was evident from the growing difference seen between the percentage of VDD/R mode primary implants and replacements (9.7% vs 18.1%). The most-used mode was sequential pacing with 2 leads (DDD/R), at 46.2% of all implanted generators (49% of primary implants and 44.2% of replacements) (Figure 10). In DDD/R devices, biosensors allowing pacing frequency variation were used practically as standard, in 97.6%.

Biventricular pacing for CRT continued its growing trend in both defibrillator-associated mode and pacemaker-associated mode. In 2014, 89 more CRT-P units were implanted than in the previous year, reflecting an increase of 10.4% (20 units/million population). Of the countries that reported data to EUCOMED, Spain performed the fewest CRT-D implants, and the third fewest CRT-P implants, ahead of only Greece and Poland.17,18

Pacing Mode SelectionAtrioventricular BlockTo assess the appropriate use of the most-recommended pacing modes,15,16 the study was limited to patients in sinus rhythm, excluding patients with permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia with AVB, code C8 of the EPPIC. Possible factors that could have influenced selection were analyzed, such as patient age and sex and degree of block.

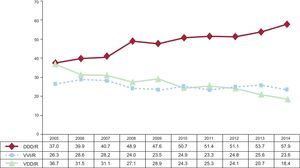

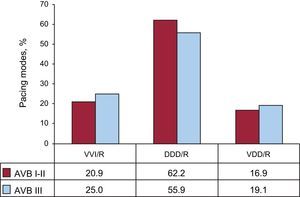

Pacing synchronous with the atrium (DDD/R and VDD/R modes) was mostly used (76.4%) and continued to show a clear upward trend, mainly due to the increase in DDD/R mode (57.9%) with an associated progressive reduction in the use of VDD/R mode (18.4%) and VVI/R mode (23.6%) (Figure 11).

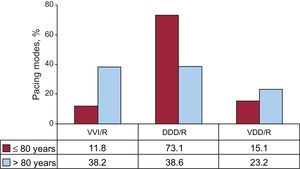

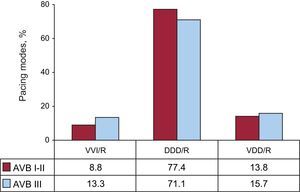

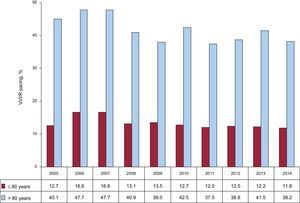

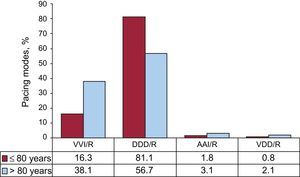

Pacing modes based on preserving atrioventricular synchrony were analyzed according to age, using 80 years as a cutoff point. The analysis showed that age greatly influenced the pacing mode chosen. In patients ≤ 80 years old, pacing with preserved atrioventricular synchrony was clearly the most frequently used (in 88.2% of cases), with DDD/R being the most widely-used mode (73.1%). Conversely, in patients older than 80 years, use of pacing with preserved atrioventricular synchrony decreased significantly to 61.8%, while VVI/R pacing comprised 38.2%. It was also noted that VDD/R mode was used more frequently (23.2%), to the detriment of DDD/R (38.6%), in patients older than 80 years with AVB than in patients aged ≤ 80 years. In those younger than 80 years with AVB, VDD/R mode was used in just 15.1% of cases (Figures 12 and 13).

Atrial-based pacing was analyzed according to the degree of AVB. The analysis showed more use in patients with first and second degree AVB (79.1%) than in those with third degree AVB (75%). These differences were due to an increased use of DDD/R mode in first and second degree AVB, a trend that has been observed in recent years (Figure 14).9–14 This difference between degrees of AV block was maintained independently of patient age (cutoff point 80 years), although it was more pronounced in older patients (Figures 15 and 16).

Pacing modes in atrioventricular block by degree of block I-II and III, 2014. AVB, atrioventricular block; DDD/R, sequential pacing with 2 leads; VDD/R, single-lead sequential pacing; VVI/R, single-chamber ventricular pacing. VDD/R, single-lead sequential pacing; VVI/R, single-chamber ventricular pacing.

As occurred in previous years, differences persisted in pacing mode selection according to sex11–14: DDD/R pacing was used more often in men than in women, whereas VDD/R pacing was used more in women than in men. In women ≤ 80 years, the percentage use of DDD/R mode was up to 5 points lower than in men (69.7% vs 75.1%), due to more frequent use in women than in men of both VDD/R mode (18.1% vs 15.1%) and VVI/R mode (12.2% vs 9.9%). Overall, sequential pacing was used 2.6% less in women aged ≤ 80 years and 4.6% less in the group of women older than 80 years than in the equivalent male groups.

When the diagnostic electrocardiogram showed AVB with preserved sinus rhythm, there remained a high percentage of patients receiving single-chamber ventricular VVI/R pacing. This pacing mode comprised 23.6% of the total (Figure 11). It is indicated particularly in older patients (Figures 12 and 17), and its use was somewhat higher in third degree block (Figure 14) and in women from both age groups.

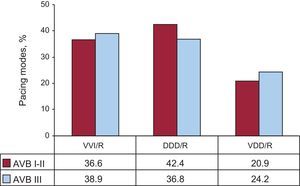

Intraventricular Conduction DefectsIn this group of patients, dual chamber pacing in DDD/R mode remained the most widely used mode (61% of implants), followed by pacing in VVI/R mode (25.6%) and VDD/R mode (13.4%) (Figure 18). In general, pacing that preserved atrioventricular synchrony was mostly used (74.4% of total implants). Compared with data from recent years,5–14 DDD/R pacemaker use increased slightly, balanced by a similar reduction in single-chamber VVI/R pacemaker use.

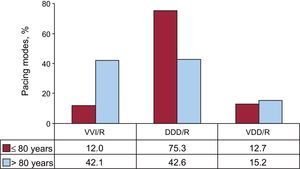

The pacing mode in this subgroup of patients was again determined by patient age, as occurred in patients with AVB. Pacing in VVI/R mode was much more common in patients older than 80 years (42.1% of implants) than in those ≤ 80 years. In those older than 80 years, the percentage VVI/R devices implanted equaled that of DDD/R devices (42.6%), In contrast, in patients aged ≤ 80 years, VVI/R mode was used in just 12% of cases, and DDD/R mode was the most widely-used (75.3%). However, and unlike what occurred in previous years, there were no differences in the use of VDD/R mode between older and younger patients (15.2% vs 12.7%) (Figure 19).

Devices with CRT-P for the treatment of ventricular dysfunction comprised 11.3% of all implanted units in this group of electrocardiographic abnormalities, reflecting an increase of 30% compared with those implanted the previous year. Again, CRT-P device implants were more common in patients aged ≤ 80 years (14.6% of implants) than in those older than 80 years (9.1%). In contrast to what occurred in the 2013 SPR, in the group of patients aged ≤ 80 years, there were no differences in the use of CRT-P in patients with an intraventricular conduction defect in terms of sex (15.6% of women and 16% of men). However, among patients older than 80 years, CRT-P was used more frequently in women (11.3%) than in men (8.3%).

Sick Sinus SyndromeThe appropriateness of pacing modes in line with current recommendations of clinical practice guidelines15,16 was assessed by dividing patients into 2 large groups. One group contained patients that were theoretically in permanent AF or flutter with associated bradycardia (code E6 of the EPPIC), and the other group contained patients that theoretically remained in sinus rhythm.

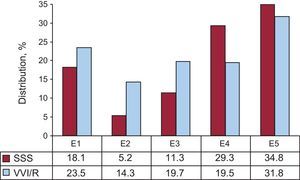

Sick Sinus Syndrome in Permanent Atrial Tachyarrhythmia. As would be expected in this situation, most implanted generators were VVI/R (95.1%). However, 4.7% received a DDD/R generator and 0.2% received a VDD/R device, which is hard to justify in SSS. Use of DDD/R mode could be explained by the presence of patients in whom restoration of sinus rhythm is expected.

Sick Sinus Syndrome in Sinus Rhythm. In the remaining electrocardiographic manifestations of SSS, the predominant rhythm was sinus rhythm, either stable or intermittent. Therefore, the most widely used pacing mode was DDD/R (70.3%) as recommended in current clinical practice guidelines, followed by VVI/R mode (26.2%), AAI/R mode (2.3%), and VDD/R mode (1.3%). As in recent years, the percentage of patients with pacing in AAI/R mode continued to decrease, probably following the recommendations of the latest clinical practice guidelines published in 20134–14 (Figure 20). Meanwhile, there remained a significant percentage of patients with SSS receiving single-chamber pacing, when, at least theoretically and without taking other factors into account, this is not the most appropriate pacing mode for SSS. Also, 1.3% of patients received a VDD/R device, which is hard to justify in this context, unless there were technical barriers to atrial lead implantation (Figure 20). The different electrocardiographic manifestations of SSS were analyzed, excluding the subgroups E7 and E8 of the EPPIC (interatrial block and chronotropic incompetence) due to their minimal representation. This analysis showed that over the years, a VVI/R pacing rate ranged from 14.3% to 31.8%, the higher percentage corresponding to bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (Figure 21). However, these data may have been magnified, as patients with permanent AF with fast-slow episodes were erroneously included in this group and not in group E6 mentioned above (Figure 22). Regarding the influence of age on pacing mode selection in SSS, as occurred with AVB, in patients aged ≤ 80 years, there was more frequent use of pacing modes that permit detection and pacing in the atrium, that is, AAI/R and DDD/R (1.8% and 81.1%, respectively) compared with just 16.3% for VVI/R mode. However, in the population group older than 80 years, VVI/R mode was used much more frequently (38.1% vs 56.7% DDD/R and 3.1% AAI/R) (Figure 22). These figures are consistent with those obtained in recent years. There remained a small percentage of VDD/R mode in both age groups (0.8% and 2.1%, respectively) (Figure 22). Age was shown to be a factor influencing mode selection throughout the years studied (Figures 23 and 24). Regarding analysis of the influence of patient sex on pacing mode selection, it was notable that in the older population group (> 80 years), VVI/R mode was used 2.9% more in men than in women. However, in patients aged ≤ 80 years, it was used 3.4% more in women than in men.

Distribution of the percentage of single-chamber ventricular pacing according to the electrocardiographic codes of the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card in sick sinus syndrome, 2014. E1, sick sinus syndrome not specified; E2, exit block; E3, sino-atrial arrest; E4, bradycardia; E5, bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; VVI/R, single-chamber ventricular pacing.

In 2014, total use of pacemaker generators in Spain showed a slight increase of 1.1% compared with the previous year, which was consistent with the trend observed in recent years. This trend is principally explained by the progressive population aging (mean age at primary implant, 77.3 years), while the total population in Spain progressively decreased. The total number of implants per million population was 784, representing an increase of 29 units/million compared with the previous year. If these figures are compared with data from the European Heart Rhythm Association white book,17 the number of implants per million population in Spain is in the third quartile, well above the mean implant rate of the 56 countries sending information to this registry (532 units/million in 2013). However, it must be taken into account that the European Heart Rhythm Association white book includes north African countries with lower per capita income and health care spending per million population than Spain. Comparison of our data with those of the 18 European countries that report their activity to EUCOMED revealed that the Spanish mean conventional pacemaker implant rate is well below the mean of the other European countries (944 units/million). Men continued to receive higher percentages of primary implants and replacements than women, which is fundamentally explained by the higher incidence of intraventricular conduction defects and AVB in men than in women. The highest frequency of implants remained in the age range 80-89 years.

Regarding CRT device implantation, the total number of implants of 7 units/million significantly increased in 2014 compared with 2013 (to 65.2 units/million). This increase was divided equally between CRT-P and CRT-D devices, as both showed an increase of 10.4%. Despite this increase, of all the countries that report data to EUCOMED, Spain remained the country with fewest CRT-D device implants and the third fewest CRT-P device implants. This situation has remained stable over recent years and did not seem to be influenced directly by the economic crisis that has affected Spain and other countries since 2007. Furthermore, it must be taken into account that current clinical guidelines recommend considering CRT-P for patients with heart failure, reduced ejection fraction, and indication for conventional cardiac pacing for whom a high percentage of ventricular pacing is anticipated, to reduce the risk of worsening heart failure,15 which should mean an even greater increase in CRT-P.

Another important aspect to highlight is the existence of significant differences in implant rates between autonomous communities. Among the main reasons that could explain these differences are the uneven distribution of arrhythmia units and heart failure units and the different mean population ages. However, in some specific cases these differences are hard to explain. For example, it was noted that in some communities such as Cantabria and the Chartered Community of Navarre, more than double the number of CRT units (CRT-P and CRT-D) per million population were implanted than in other communities such as Catalonia or Andalusia. There was also a notable increase in the general rate of pacemaker implants in Extremadura between 2013 and 2014, with a marked decrease in CRT, mainly due to fewer CRT-D implants.

Most of the electrodes used were bipolar (except in the case of left ventricular pacing via the coronary sinus) and the use of active fixation systems continued to increase (84.2%), both in the atrium and ventricle. This was probably due to the potential it offers to implant the electrode in alternative sites (with the aim of achieving more physiological pacing),22 the good electric performance of these electrodes, and the greater ease of future repositioning and removal if necessary. Regarding electrodes compatible with magnetic resonance imaging, their use did not increase compared with previous years, and the criteria for their implantation was unknown. It is possible that their use, along with generators compatible with magnetic resonance imaging, belonging to the high-end of the price range, makes the implant expensive, and therefore infrequently used. However, implantation of this type of electrode would be advisable, given the increased probability that patients with devices, of progressively older age and with associated morbidity, will require magnetic resonance imaging in the future.23 For this reason, nowadays most manufacturers routinely market their pacing leads with protection for magnetic resonance imaging without additional cost and therefore it is likely that their use will increase significantly in the coming years.

As in previous years, the most common electrocardiographic abnormality prior to implantation was AVB, principally due to third degree AVB. In AVB, pacing synchronous with the atrium continued to be the most common mode (76.3%), above all because of the increase in DDD/R mode (57.9%) and the progressive decrease of VDD/R and VVI/R pacing. Age is known to influence atrial-based pacing mode, which comprised 88.2% of pacemaker modes in patients younger than 80 years, while more than a third of patients older than 80 years received VVI/R pacing. Likewise, VDD/R mode pacing to maintain atrioventricular synchrony was used more often in those older than 80 years than in those younger than 80 years (23.2% vs 15.1%), and in replacements more than in primary implants (18.5% vs 9.7%).

In SSS, atrial-based pacing mode continued to be used most, with a predominance of DDD/R mode (70.3%), as recommended by current clinical practice guidelines. However, VVI/R mode continued to be used in 26.2% of all cases of SSS, particularly in patients older than 80 years (38.1%) and in the bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome type of SSS (37.6%). This could be because of the risk of going into permanent AF in the near future or because patients with permanent slow-fast AF were erroneously included in this group. Either way, the guidelines recommend pacing with DDD/R mode in SSS, given that it offers a reduction in the incidence of AF and stroke and a lower risk of developing pacemaker syndrome, which could worsen patients’ quality of life. Pacing in AAI/R mode continued to decrease in line with current clinical guidelines, based on the results of the DANPACE trial24 and the disadvantage of this pacing mode, considering that each year 0.6% to 1.9% of patients with SSS experience AVB. In atrial tachyarrhythmia with slow ventricular response, the most widely used mode was VVI/R (almost 95.1% of cases), with a small percentage of atrial-based pacing, probably in patients who were expected to achieve recovery of sinus rhythm.

In intraventricular conduction defects, DDD/R mode was most frequently used (61%), followed by VVI/R mode in a quarter of patients. Also in this indication group, there were differences according to age: in patients older than 80 years, almost the same proportion of patients were paced in DDD/R mode as in VVI/R mode; while in those younger than 80 years, there was a marked difference (DDD/R vs VVI/R, 75.3% vs 12%). The VDD/R mode was used less frequently and without differences based on age. Pacing with CRT-P comprised 11.4% of procedures with this electrocardiographic indication, and was somewhat lower in patients older than 80 years (9.1% vs 14.6%). There were no differences in CRT-P by sex among younger patients, and there was a slight predominance of women in older patients (11.3% vs 8.3%), possibly related to the results of the MADIT-CRT trial on the increased effectiveness of this therapy in women.25

CONCLUSIONSThe slow increase in the use of pacemakers and CRT devices continued, although Spain remained far below the European average. There were significant differences in the rate of implants among the autonomous communities, especially for CRT devices. There was generalized use of active fixation leads, and the rate of use of electrodes compatible with magnetic resonance imaging continued to increase, although it remained insufficient. Patient age and sex continued to influence correct pacing mode selection.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.