We have read with interest the article by Fernández-Vázquez et al.1 on the changes seen in cause of death among patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). We would like to commend the authors for their interesting and carefully conducted multicenter study. These authors compared 2 prospective registries of patients with HFrEF: MUSIC (inclusion period, 2003-2004) and REDINSCOR-I (inclusion period, 2007-2011). The 2 registries had a total of 2351 patients who completed a 4-year follow-up period. The study showed that drug therapy had a positive impact on lowering mortality, mainly due to a decrease in sudden cardiac death, confirming tendencies observed in previous studies.2 The percentage of noncardiovascular death was very low (6.6% at 4 years), accounting for around 20% of all deaths, with no significant differences seen between MUSIC (19%) and REDINSCOR-I (20%).

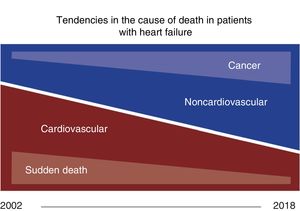

We recently published a study analyzing the cause of death (n=935) in 1876 patients with HF and ejection fraction<50% in the past 18 years.3 Our results can be summarized in 2 main tendencies (figure 1): a gradual reduction in cardiovascular death, mainly sudden cardia death, and a sizeable increase in noncardiovascular death, with cancer being the main cause (37%). As a whole, noncardiovascular deaths comprised 40.4% of deaths, but this percentage rose significantly and progressively from 17% (4/23) in 2002 to 65% (48/73) in 2018, a rise that was particularly evident in the last 3 years (2016-2018), when the figure was 53% (117/219).

Several reasons could explain the differences between our study and previous ones:

The populations studied were slightly different. Although there were no significant differences in age or comorbidities, REDINSCOR-I patients had slightly lower ejection fraction (28% vs 31%), somewhat higher NT-proBNP (1959 vs 1750 ng/L), and most importantly, worse functional class (57% in classes III-IV vs 26%) than seen in our population. Moreover, the patients in our cohort were more likely to have received angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (86% vs 90%, 85% vs 92%, and 64 vs 68%, respectively).

Furthermore, the study design was different: we did not analyze mortality at a specific follow-up time point to compare 2 inclusion periods (2003-2004 vs 2007-2011), but rather the causes of death per calendar year from 2002 to 2018. Additionally, a third reason could be the very long follow-up period of our study, allowing us to evaluate a higher number of fatal events and the cause of late death in patients who did not die in the early years of follow-up, which was cardiovascular in many cases.

Last, we consider the different periods used for the analysis to be relevant. Patients were included in MUSIC until 2004 and in REDINSCOR-I until 2011, with follow-up ending in 2008 and 2015, respectively. In our work, the analysis lasted until 2018 and, as mentioned before, the largest increase in noncardiovascular deaths occurred in the final 3 years, after the studies mentioned. This might have allowed us to more readily assess the consequences of demographic changes in recent years, including the rising prevalence of comorbidities and cancer in the clinical course of these patients (increasingly more common in those with HF), with the ensuing increase in noncardiovascular mortality. Moreover, in our study's final years of follow-up, patients were able to benefit from new treatments, such as ivabradine (2012) and sacubitril-valsartan (2016), which were only included in the European HF Guidelines after REDINSCOR-I was completed and which improve the prognosis of HFrEF.

Based on our experience, changes in the cause of death among contemporary patients with HFrEF could suggest the need for changes in the treatment of this condition (figure 2).4

Implications of changes in the cause of death (reproduced and modified with permission from Patel et al.4). HF, heart failure; HFrEF, HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.