Over recent years, sacubitril/valsartan has become an increasingly common treatment for patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Its use is supported by its excellent outcomes in terms of reduced mortality, improved symptoms, and preventing readmission, which has revolutionized the treatment of these patients.1

Sacubitril is a prodrug whose mechanism of action is inhibition of neprilysin, an enzyme that metabolizes atrial and brain natriuretic peptides. This inhibition is produced by an active metabolite of sacubitril (sacubitrilat).

Neprilysin has been implicated in the degradation of beta-amyloid protein (involved in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases). This has led to some authors raising concern about its possible effects on the brain and the possible association between sacubitril and cognitive decline. Although some clinical trials are underway on this topic, taking sacubitril has not consistently been associated with adverse cognitive effects.2,3 Considering its involvement in brain function, it could be postulated as potentially being involved in the onset of psychiatric symptoms. However, there have been very few reports.4

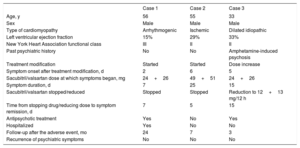

We present a series of 3 cases of psychiatric symptoms after starting or increasing the dose of sacubitril/valsartan. In the 3 cases there was a clear temporal association between starting or increasing the dose of the drug and symptom onset, and improvement after stopping it or lowering the dose. The characteristics of each patient and the chronology of the adverse effects are shown in table 1. Here we present the psychiatric symptoms of each case.

Baseline characteristics of patients and summary of the adverse events

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 56 | 55 | 33 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male |

| Type of cardiomyopathy | Arrhythmogenic | Ischemic | Dilated idiopathic |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 15% | 29% | 33% |

| New York Heart Association functional class | III | II | II |

| Past psychiatric history | No | No | Amphetamine-induced psychosis |

| Treatment modification | Started | Started | Dose increase |

| Symptom onset after treatment modification, d | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Sacubitril/valsartan dose at which symptoms began, mg | 24+26 | 49+51 | 24+26 |

| Symptom duration, d | 7 | 25 | 15 |

| Sacubitril/valsartan stopped/reduced | Stopped | Stopped | Reduction to 12+13 mg/12 h |

| Time from stopping drug/reducing dose to symptom remission, d | 7 | 5 | 15 |

| Antipsychotic treatment | Yes | No | Yes |

| Hospitalized | Yes | No | No |

| Follow-up after the adverse event, mo | 24 | 7 | 3 |

| Recurrence of psychiatric symptoms | No | No | No |

The first case was a 56-year-old man with no psychiatric history. Two days after starting sacubitril/valsartan treatment (dose, 24+26mg/12h), symptoms began, consistent with verbosity, dysphoria, and irritability, along with mixed delusional ideation (grandiose and mystic) with suspiciousness, self-reference, and generalized paranoia. He had psychomotor agitation and resistant insomnia. He had no hallucinatory symptoms. He required admission as a psychiatric inpatient, sacubitril/valsartan was stopped, and treatment with haloperidol was started. The symptoms resolved after 7 days, and he was discharged. He had partial amnesia for the episode. Treatment with haloperidol was continued and then switched to aripiprazole for 4 months. Eventually, he received a heart transplant, and the antipsychotic medication was stopped. He is currently followed-up by cardiology and psychiatry and has not had a recurrence of the psychiatric symptoms.

The second case was a 56-year-old man with no past psychiatric history. Six days after starting sacubitril/valsartan (dose, 49+51mg/12h), he developed symptoms of irritability toward his family members, motivated by delusional ideation of harm with severe behavioral effects (aggression toward family members and temporarily leaving home). These symptoms were associated with psychomotor agitation and persistent general insomnia. He had no hallucinatory symptoms. The symptoms lasted a total of 25 days, during which the patient did not seek medical attention. His family members reported these symptoms to his cardiologist, who decided to stop the drug. Five days after stopping, the symptoms gradually resolved, with partial amnesia for the episode. The patient received no antipsychotic treatment. Mental state assessment was performed 2 months after the drug was stopped, confirming complete symptom resolution. Currently he is stable and under follow-up by cardiology and psychiatry.

The third case was a 33-year-old man, with history of amphetamine-induced psychosis 10 years prior, requiring short-term treatment with amisulpride; at the time of symptom onset he was not using any substances. The patient had been on treatment with sacubitril/valsartan at a subtherapeutic dose of 12+13mg/12h (due to hypotension) for 4 months. The dose was increased to 24+26mg/12h and 5 days later the patient started having delusional ideation similar to his first episode, with agitation and insomnia. When this was reported to his cardiologist, it was decided to reduce the dose to 12+13mg/12h again (which has been continued at follow-up). The patient was assessed by the psychiatrist, who already knew him, and was started on antipsychotic treatment with amisulpride. This was followed by substantial symptom improvement.

In the 3 cases presented here, psychotic symptoms (mainly delusional) began shortly after exposure to or an increase in dose of a drug: sacubitril/valsartan. Consequently, these episodes would correspond to the diagnosis of “substance or medication induced psychotic disorder” (DSM 5 292.9; ICD 10 F19.959)5. The 3 cases involved serious adverse effects with significant clinical repercussions for the patients and their families.

Although there are limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn from these cases, we cannot ignore the timing of symptom onset in relation to starting or increasing the dose of the drug and their resolution after stopping or reducing the dose (in 1 of the cases, spontaneously, without antipsychotic treatment). This could mean that psychotic symptoms may be an uncommon adverse effect of sacubitril/valsartan. When we reviewed our patient population on treatment with sacubitril/valsartan, we found no more cases with such a direct association between taking the drug and psychiatric symptoms.

The mechanisms by which neprilysin inhibition may produce psychiatric symptoms, as well as their true incidence, remain unknown. The hypothetical accumulation of beta-amyloid protein appears unlikely, since these episodes had an acute onset and resolution. Given the lack of available evidence, further studies would be beneficial.