The optimal timing of coronary angiography in patients admitted with non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS) as well as the need for pretreatment are controversial. The main objective of the IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry was to assess the proportion of patients undergoing an early invasive strategy (0-24hours) without dual antiplatelet therapy (no pretreatment strategy) in Spain.

MethodsThis observational, prospective, and multicenter study included consecutive patients with NSTEACS who underwent coronary angiography that identified a culprit lesion.

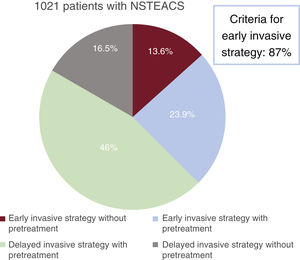

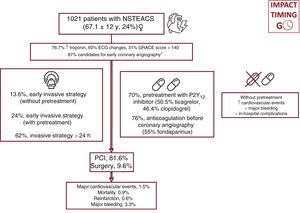

ResultsBetween April and May 2022, we included 1021 patients diagnosed with NSTEACS, with a mean age of 67±12 years (23.6% women). A total of 87% of the patients were deemed at high risk (elevated troponin; electrocardiogram changes; GRACE score>140) but only 37.8% underwent an early invasive strategy, and 30.3% did not receive pretreatment. Overall, 13.6% of the patients underwent an early invasive strategy without pretreatment, while the most frequent strategy was a deferred angiography under antiplatelet pretreatment (46%). During admission, 9 patients (0.9%) died, while major bleeding occurred in 34 (3.3%).

ConclusionsIn Spain, only 13.6% of patients with NSTEACS undergoing coronary angiography received an early invasive strategy without pretreatment. The incidence of cardiovascular and severe bleeding events during admission was low.

Keywords

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death in developed countries.1 Its incidence, especially that of non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS), has risen in recent years.2 The most common underlying pathophysiologic mechanism is atheromatous plaque rupture or erosion leading to platelet aggregation and subsequent intraluminal thrombus formation. Most patients receive specific antithrombotic therapy and an invasive strategy.1,2 In its 2020 guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of NSTEACS,1 the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) introduced several modifications to its recommendations on antithrombotic treatment and revascularization strategies, some of which have given rise to controversy.3 Of note, the ESC now recommends routine catheterization within 24 hours of admission for high-risk patients1 (level of evidence IA) and no longer recommends a 72-hour window for intermediate-risk patients.4 It also advises against routine antiplatelet pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor-ticagrelor, prasugrel, or clopidogrel-when early invasive intervention is planned.

Nonetheless, and despite the ESC recommendations, the main studies in the literature have not demonstrated the benefits of a routine early invasive strategy.5–11 In the case of pretreatment strategies, prasugrel12 and ticagrelor13 have not been found to reduce thrombotic events in NSTEACS, and prasugrel12 (but not ticagrelor13) may even increase the risk of major bleeding. The recent ISAR-REACT (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment) 5 trial demonstrated the superiority of no pretreatment with prasugrel over pretreatment with ticagrelor.14 It is important to note, however, that time to coronary angiography in the above-mentioned studies was just a few hours.12,14

The most recent reports on the management of NSTEACS in Spain were published before the latest clinical practice guidelines.15–17 The IMPACT-TIMING-GO (Impact of Time of Intervention in Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Non–ST-Segment Elevation. Management and Outcomes) registry was designed to assess current clinical practices in Spain regarding the timing of coronary angiography and the use of pretreatment in patients with NSTEACS.

MethodsStudy designThe IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry is a prospective, observational, multicenter registry of data collected by 23 Spanish hospitals (table 1 of the supplementary data). The registry is an initiative of the Young Cardiologists Group of the Spanish Cardiology Society. The study was designed in according with the STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines and is described elsewhere.18 The protocol was approved by the drug research ethics committees at all participating hospitals and complies with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

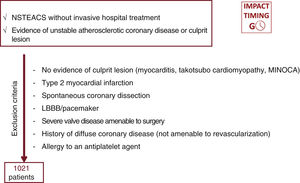

Study populationAll patients with NSTEACS (defined as NSTE myocardial infarction [NSTEMI] or unstable angina) in whom coronary angiography revealed unstable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or a culprit lesion were consecutively included, irrespective of the treatment modality used by the attending medical team (figure 1). Exclusion criteria were type 2 myocardial infarction, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, spontaneous coronary artery dissection, a history of nonrevascularizable coronary artery disease (CAD), and any cause of troponin elevation without evidence of CAD (myocarditis, coronary spasm, etc.).18 The following information was collected: main baseline characteristics, angiographic findings, medical treatments, time to coronary angiography, clinical course during hospitalization, and treatment at discharge. In all patients, intraprocedural antiplatelet therapy and materials and devices were chosen by the medical team in line with usual clinical practice.

Objectives and definitionsThe primary objective of this study was to determine the percentage of patients in the IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry who underwent coronary angiography within 24 hours of admission to hospital and who received dual antiplatelet pretreatment with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor in line with clinical practice guideline recommendations. The fourth universal definition was used for NSTEMI.19 NSTEACS was deemed to be high risk when at least 1 of the following criteria was met: myocardial infarction, new or dynamic electrocardiographic (ECG) changes to the T wave/ST-segment suggestive of ischemia, transient ST-segment elevation, and a Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score >140. Invasive approaches were classified as early when coronary angiography was performed within 24 hours of admission and delayed when performed later. Patients treated with a P2Y12 inhibitor in combination with aspirin before coronary angiography were assigned to the pretreatment group.

We defined a composite endpoint of in-hospital cardiovascular events that included all-cause mortality and reinfarction and a safety endpoint including incidence of major (type 3, 4, or 5) bleeding according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) scale.20 We also defined a composite endpoint of in-hospital complications that, in addition to the above-mentioned complications, included acute kidney failure (50% increase in creatinine levels from baseline or need for extrarenal clearance), atrial fibrillation or ventricular arrhythmias, acute confusional state, and mechanical complications of myocardial infarction.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are expressed as number (%) and quantitative variables as mean±standard deviation. Nonnormally distributed quantitative variables are expressed as median [interquartile range]. Normality of distribution was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Quantitative variables were compared using the t test, analysis of variance, the Mann-Whitney test, or the Kruskal-Wallis test, while categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher exact test. A 2-tailed P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp, USA).

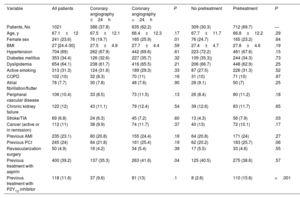

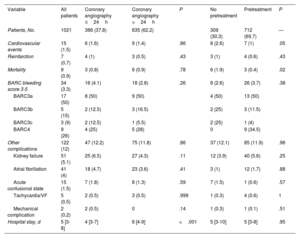

ResultsWe included 1021 patients (mean age, 67.1±12 years; 23.6% women) with NSTEACS who underwent coronary angiography between April 1 and May 31, 2022. Overall, 37.8% of patients underwent this procedure within 24 hours of admission and 30.3% did not receive dual antiplatelet pretreatment. An early invasive strategy without pretreatment was used in 13.6% of patients (figure 2 and figure 3). The most common approach was a delayed invasive strategy with pretreatment (46% of patients). The main baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in table 1. The only differences between the treatment groups (delayed vs early invasive strategy and pretreatment vs no pretreatment) were a higher proportion of women in the delayed strategy group (19.7% vs 25.9%, P=.01) and a higher prevalence of previous stroke in the pretreatment group (7.9% vs 4.3%, P=.03).

Baseline characteristics of study population overall and by treatment strategy

| Variable | All patients | Coronary angiography ≤24h | Coronary angiography >24h | P | No pretreatment | Pretreatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | 1021 | 386 (37.8) | 635 (62.2) | 309 (30.3) | 712 (69.7) | — | |

| Age, y | 67.1±12 | 67.5±12.1 | 66.4±12.3 | .17 | 67.7±11.7 | 66.8±12.2 | .29 |

| Female sex | 241 (23.6) | 76 (19.7) | 165 (25.9) | .01 | 76 (24.7) | 165 (23.2) | .64 |

| BMI | 27 [24.4-30] | 27.5±4.9 | 27.7±4.4 | .59 | 27.4±4.7 | 27.8±4.6 | .19 |

| Hypertension | 704 (69) | 262 (67.9) | 442 (69.6) | .61 | 223 (72.2) | 481 (67.6) | .15 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 353 (34.4) | 126 (32.6) | 227 (35.7) | .32 | 109 (35.3)) | 244 (34.3) | .73 |

| Dyslipidemia | 654 (64.1) | 238 (61.7) | 416 (65.5) | .21 | 206 (66.7) | 448 (62.9) | .25 |

| Active smoking | 313 (31.3) | 124 (31.6) | 189 (29.3) | .33 | 87 (27.5) | 226 (31.3) | .52 |

| COPD | 102 (10) | 32 (8.3) | 70 (11) | .16 | 31 (10) | 71 (10) | .97 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 78 (7.7) | 30 (7.8) | 48 (7.6) | .90 | 28 (9.1) | 50 (7) | .25 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 106 (10.4) | 33 (8.5) | 73 (11.5) | .13 | 26 (8.4) | 80 (11.2) | .18 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 122 (12) | 43 (11.1) | 79 (12.4) | .54 | 39 (12.6) | 83 (11.7) | .65 |

| Stroke/TIA | 69 (6.8) | 24 (6.3) | 45 (7.2) | .60 | 13 (4.3) | 56 (7.9) | .03 |

| Cancer (active or in remission) | 112 (11) | 38 (9.9) | 74 (11.7) | .37 | 40 (13) | 72 (10.1) | .17 |

| Previous AMI | 235 (23.1) | 80 (20.8) | 155 (24.4) | .18 | 64 (20.8) | 171 (24) | .27 |

| Previous PCI | 245 (24) | 84 (21.8) | 161 (25.4) | .19 | 62 (20.2) | 183 (25.7) | .06 |

| Revascularization surgery | 50 (4.9) | 16 (4.2) | 34 (5.4) | .39 | 17 (5.5) | 33 (4.6) | .55 |

| Previous treatment with aspirin | 400 (39.2) | 137 (35.3) | 263 (41.6) | .04 | 125 (40.5) | 275 (38.6) | .57 |

| Previous treatment with P2Y12 inhibitor | 118 (11.6) | 37 (9.6) | 81 (13) | .1 | 8 (2.6) | 110 (15.6) | <.001 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Values are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

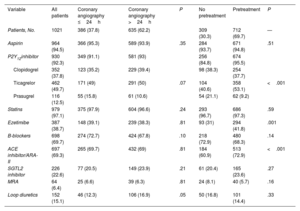

The main clinical variables and in-hospital treatments are summarized in table 2 and table 2 of the supplementary data. Overall, 87% of patients had a least 1 of the high-risk criteria for an early invasive strategy set out in the clinical practice guidelines.1 Ticagrelor (50.5%), followed by clopidogrel (46.4%), was the most common antiplatelet agent used in pretreated patients (69.7% of the population). Seventy-six percent of patients received anticoagulant therapy before coronary angiography. Fondaparinux (55%) was the main agent used. Patients who underwent early angiography were more likely to have elevated troponin (86.2% vs 71.5%, P<.001), ECG changes (57.9% vs 47%, P=.001), transient ST-segment elevation (15.7% vs 5.1%, P<.001), a GRACE score >140 (35.5% vs 28.1%, P=.01), and refractory chest pain (6.5% vs 0.6%, P<.001) (table 2). They were also more likely to be admitted to intensive care (62% vs 36.7%, P<.001) and less likely to receive pretreatment (63.5% vs 73.5%, P=.001). Patients who were not pretreated were less likely to have NSTEMI (70.5% vs 79.8%, P=.001), transient ST-segment elevation (6.2% vs 10.4%, P=.03), and chest pain at rest (64.9% vs 72.7%, P=.01). These patients were also less likely to be admitted to intensive care (9.4% vs 19.7%, P<.001) and to receive anticoagulation before coronary angiography (67.8% vs 79.8%, P<.001) and more likely to receive an early invasive strategy (45.6% vs 34.4%, P=.001). Finally, patients admitted to hospitals with a catheterization laboratory were more likely to receive an early invasive strategy without pretreatment.

Clinical, angiographic, and treatment characteristics of study population overall and by treatment subgroup

| Variable | All patients | Coronary angiography ≤24h | Coronary angiography >24h | P | No pretreatment | Pretreatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | 1021 | 386 (37.8) | 635 (62.2) | 309 (30.3) | 712 (69.7) | - | |

| SBP on admission, mmHg | 143±25 | 143±25 | 143±24 | .80 | 143±35 | 143±25 | .79 |

| DBP on admission, mmHg | 79.9±15 | 79.9±15 | 79.9±14 | .99 | 80±15 | 80±15 | .69 |

| HR on admission, bpm | 76±16 | 76±15 | 75±16 | .43 | 76±25 | 75±16 | .40 |

| Admission unit | |||||||

| ICU | 169 (16.6) | 65 (17.2) | 104 (16.3) | 29 (9.4) | 140 (19.7) | ||

| Cardiology ICU | 303 (29.8) | 172 (44.8) | 131 (20.4) | 93 (30.2) | 210 (29.6) | ||

| Cardiology ward | 444 (43.5) | 105 (27.1) | 339 (53.6) | <.001 | 155 (50) | 289 (40.6) | <.001 |

| Emergency department | 78 (7.7) | 33 (8.6) | 45 (7.1) | 22 (7.1) | 56 (7.9) | ||

| Hospital with catheterization laboratory | 769 (75.7) | 313 (81.9) | 456 (71.9) | <.001 | 248 (80.8) | 521 (73.5) | .01 |

| Candidates for coronary angiography within 24 h | 871 (86.8) | 353 (93.4) | 518 (82.9) | <.001 | 250 (82.2) | 621 (88.8) | .004 |

| Prior ischemia detection test | 82 (8.1) | 19 (5) | 63 (10) | .005 | 40 (13.1) | 42 (5.9) | <.001 |

| Killip class on admission | |||||||

| I | 914 (89.7) | 348 (90) | 566 (89.5) | 271 (88.3) | 643 (90.3) | ||

| II | 75 (7.5) | 29 (7.6) | 46 (7.5) | .89 | 25 (8.4) | 50 (7.1) | .64 |

| III-IV | 28 (2.7) | 9 (2.4) | 19 (3) | 10 (3.3) | 18 (2.6) | ||

| Chest pain at rest | 716 (70.1) | 286 (74.7) | 430 (67.7) | .02 | 200 (64.9) | 516 (72.7) | .01 |

| ECG changes | 519 (51.1) | 221 (57.9) | 298 (47) | .001 | 146 (47.4) | 373 (52.7) | .12 |

| Transient ST-segment elevation | 92 (9) | 60 (15.7) | 32 (5.1) | <.001 | 19 (6.2) | 73 (10.4) | .03 |

| NSTEMI | 783 (767) | 330 (86.2) | 453 (71.5) | <.001 | 217 (70.5) | 566 (79.8) | .001 |

| GRACE score >140 | 309 (30.9) | 135 (35.5) | 174 (28.1) | .01 | 89 (28.9) | 220 (31.7) | .39 |

| Refractory chest pain | 31 (3.1) | 25 (6.5) | 6 (0.9) | <.001 | 11 (3.6) | 20 (2.8) | .51 |

| LVEF on admission, % | 58 [50-60] | 57 [50-60] | 59 [51-60] | .06 | 58 [50-60] | 59 [51-60] | .97 |

| Time to coronary angiography | |||||||

| ≤24 h | 386 (37.9) | 386 (100) | 0 | — | 141 (45.6) | 245 (34.4) | .001 |

| >24 h | 635 (62.1) | 0 | 635 (100) | 168 (54.4) | 467 (65.5) | ||

| Pretreatment with P2Y12inhibitor | 709 (70) | 242 (63.5) | 467 (73.5) | .001 | 0 | 712 (100) | |

| Ticagrelor | 359 (50.5) | 126 (52) | 233 (50) | — | |||

| Clopidogrel | 329 (46.4) | 106 (43.8) | 223 (47.6) | ||||

| Prasugrel | 21 (3.1) | 10 (4.2) | 11 (2.4) | ||||

| Previous anticoagulation | 762 (76.2) | 277 (74.3) | 485 (77.2) | .28 | 206 (67.8) | 556 (79.8) | <.001 |

| Fondaparinux | 419 (55) | 161 (58.1) | 258 (53.2) | 125 (60.1) | 294 (52.9) | ||

| LMWH | 325 (42.5) | 108 (39) | 217 (44.7) | 74 (35.9) | 251 (45.1) | ||

| Unfractionated heparin | 18 (2.5) | 8 (2.9) | 10 (2.1) | 7 (4) | 11 (2) | ||

| Radial access | 963 (94.3) | 368 (95.3) | 595 (93.7) | .20 | 301 (97.4) | 662 (93) | .008 |

| Diseased vessels, No | |||||||

| 1 | 483 (47.6) | 185 (48.4) | 298 (47.2) | 131 (42.5) | 353 (49.7) | ||

| 2 | 313 (30.7) | 106 (27.6) | 207 (32.6) | 89 (28.9) | 224 (31.5) | ||

| 3 | 221 (21.7) | 92 (24) | 129 (20.3) | .17 | 88 (28.6) | 133 (18.7) | .002 |

| LCAD | 134 (13.3) | 81 (14) | 53 (12.9) | .63 | 45 (14.8) | 89 (12.7) | .38 |

| Baseline TIMI score <3 | 294 (29.5) | 133 (35) | 161 (26.1) | .003 | 85 (28.2) | 209 (30) | .58 |

| No-reflow phenomenon | 25 (3) | 14 (4.6) | 11 (2.1) | .05 | 11 (4.8) | 14 (2.4) | .06 |

| Treatment | |||||||

| PCI | 831 (81.6) | 311 (81) | 520 (81.9) | 229 (74.4) | 602 (84.7) | ||

| Surgery | 98 (9.6) | 46 (12) | 52 (8.2) | 50 (16.2) | 48 (6.8) | ||

| Medical | 88 (8.6) | 25 (6.3) | 63 (9.9) | .01 | 27 (8.8) | 61 (8.6) | <.001 |

| Time from coronary angiography to surgery, d | 8 (4.7-11) | 7 (3.5-11.5) | 8 (7-10) | .49 | 8 (4-11) | 8 (5-10) | .91 |

| Thrombus aspiration | 37 (4.5) | 22 (7.1) | 15 (2.9) | .005 | 9 (3.9) | 28 (4.7) | .63 |

| Anti-GPIIb/IIIa | 22 (2.7) | 10 (3.2) | 12 (2.3) | .43 | 6 (2.6) | 16 (2.7) | .96 |

| Cangrelor | 14 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 12 (2.3) | .07 | 12 (5.2) | 2 (0.3) | <.001 |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GP, glycoprotein; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HR, heart rate; ICU, intensive care unit; LCAD, left coronary artery disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LMWH, low-molecular–weight heparin; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Values are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

In total, 47.6% of patients had 1-vessel disease, 21.7% had 3-vessel disease, and 13.3% had left main CAD. Revascularization was by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in 81.6% of patients and by coronary surgery in 9.6%. Median time from coronary angiography to surgery was 8 [4.7-11] days. Patients in the early invasive strategy group were more likely to have a TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) score <3 in the culprit artery (35% vs 26.1%, P=.003) and to undergo thrombus aspiration (7.1% vs 2.9%, P=.005). Patients who were not pretreated were more likely to require cangrelor (5.2% vs .3%, P<.001), have 3-vessel disease (28.6 vs 18.7%, P<.001), and undergo coronary revascularization surgery (16.2% vs 6.8%, P<.001).

The main in-hospital complications and treatments at discharge are shown in table 3, table 4, and table 3 of the supplementary data. Median hospital stay was 5 [3-8] days. Stays were shorter in the early invasive strategy group: 4 [3-7] vs 6 [4-9] days (P<.001). Ticagrelor (49.7%), followed by clopidogrel (37.8%) and prasugrel (12.5%), was the most common P2Y12 inhibitor prescribed at discharge. The overall complication rate was 12%: 15 patients (1.5%) had a cardiovascular event, 9 (0.9%) died, 7 (0.7%) had a reinfarction, and 34 (3.3%) had major bleeding.

In-hospital complications for study population overall and by treatment strategy

| Variable | All patients | Coronary angiography ≤24h | Coronary angiography >24h | P | No pretreatment | Pretreatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | 1021 | 386 (37.8) | 635 (62.2) | 309 (30.3) | 712 (69.7) | — | |

| Cardiovascular events | 15 (1.5) | 6 (1.6) | 9 (1.4) | .86 | 8 (2.6) | 7 (1) | .05 |

| Reinfarction | 7 (0.7) | 4 (1) | 3 (0.5) | .43 | 3 (1) | 4 (0.6) | .43 |

| Mortality | 9 (0.9) | 3 (0.8) | 6 (0.9) | .78 | 6 (1.9) | 3 (0.4) | .02 |

| BARC bleeding score 3-5 | 34 (3.3) | 16 (4.1) | 18 (2.8) | .26 | 8 (2.6) | 26 (3.7) | .38 |

| BARC3a | 17 (50) | 8 (50) | 9 (50) | 4 (50) | 13 (50) | ||

| BARC3b | 5 (15) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (16.5) | 2 (25) | 3 (11.5) | ||

| BARC3c | 3 (9) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (5.5) | 2 (25) | 1 (4) | ||

| BARC4 | 9 (26) | 4 (25) | 5 (28) | 0 | 9 (34.5) | ||

| Other complications | 122 (12) | 47 (12.2) | 75 (11.8) | .86 | 37 (12.1) | 85 (11.9) | .96 |

| Kidney failure | 51 (5.1) | 25 (6.5) | 27 (4.3) | .11 | 12 (3.9) | 40 (5.6) | .25 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 41 (4) | 18 (4.7) | 23 (3.6) | .41 | 3 (1) | 12 (1.7) | .88 |

| Acute confusional state | 15 (1.5) | 7 (1.8) | 8 (1.3) | .59 | 7 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | .57 |

| Tachycardia/VF | 5 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.5) | .999 | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.6) | 1 |

| Mechanical complication | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 0 | .14 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | .51 |

| Hospital stay, d | 5 [3-8] | 4 [3-7] | 6 [4-9] | <.001 | 5 [3-10] | 5 [3-8] | .95 |

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; VF, ventricular fibrillation.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range].

Treatments at discharge for study population overall and by treatment strategy.

| Variable | All patients | Coronary angiography ≤24h | Coronary angiography >24h | P | No pretreatment | Pretreatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | 1021 | 386 (37.8) | 635 (62.2) | 309 (30.3) | 712 (69.7) | — | |

| Aspirin | 964 (94.5) | 366 (95.3) | 589 (93.9) | .35 | 284 (93.7) | 671 (94.8) | .51 |

| P2Y12inhibitor | 930 (92.3) | 349 (91.1) | 581 (93) | 256 (84.8) | 674 (95.5) | ||

| Clopidogrel | 352 (37.8) | 123 (35.2) | 229 (39.4) | 98 (38.3) | 254 (37.7) | ||

| Ticagrelor | 462 (49.7) | 171 (49) | 291 (50) | .07 | 104 (40.6) | 358 (53.1) | <.001 |

| Prasugrel | 116 (12.5) | 55 (15.8) | 61 (10.6) | 54 (21.1) | 62 (9.2) | ||

| Statins | 979 (97.1) | 375 (97.9) | 604 (96.6) | .24 | 293 (96.7) | 686 (97.3) | .59 |

| Ezetimibe | 387 (38.7) | 148 (39.1) | 239 (38.3) | .81 | 93 (31) | 294 (41.8) | .001 |

| B-blockers | 698 (69.7) | 274 (72.7) | 424 (67.8) | .10 | 218 (72.9) | 480 (68.3) | .14 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARA-II | 697 (69.3) | 265 (69.7) | 432 (69) | .81 | 184 (60.9) | 513 (72.9) | <.001 |

| SGTL2 inhibitor | 226 (22.6) | 77 (20.5) | 149 (23.9) | .21 | 61 (20.4) | 165 (23.6) | .27 |

| MRA | 64 (6.4) | 25 (6.6) | 39 (6.3) | .81 | 24 (8.1) | 40 (5.7) | .16 |

| Loop diuretics | 152 (15.1) | 46 (12.3) | 106 (16.9) | .05 | 50 (16.8) | 101 (14.4) | .33 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARA-II, angiotensin II receptor antagonist; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; SGTL2, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2.

Values are expressed as No. (%).

The first conclusion to emerge from the Spanish IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry is the low level of compliance with NSTEACS guideline1 recommendations on coronary angiography timing and antiplatelet pretreatment: just 37.8% of patients underwent routine invasive intervention within 24 hours of admission and less than one-third were not pretreated with a P2Y12 inhibitor. The reasons behind this low level of compliance do not appear to be linked to low ischemic risk, as almost 90% of patients met at least 1 of the high-risk features for an early routine invasive strategy. Our work provides novel insights into the management of NSTEACS in Spain as this is the first report to appear since the publication of the 2020 ESC guidelines. The second conclusion to emerge from the registry is that all the treatment strategies were associated with a low rate of in-hospital ischemic and hemorrhagic complications, suggesting that real-world clinical practice based on individual risk and local catheterization capabilities is both safe and effective.

Our findings provide an interesting snapshot of the profiles of patients with NSTEACS treated with different strategies in real-world clinical practice in Spain. First, patients who underwent early coronary angiography or received pretreatment had a higher ischemic risk profile (higher prevalence of infarction and ECG changes) on admission to hospital. Second, patients who were not pretreated had a higher prevalence of 3-vessel disease and were more likely to undergo surgical revascularization, while pretreated patients had a higher prevalence of 1-vessel disease and were more likely to undergo PCI. This apparent tailoring of treatment strategies is striking as it shows that clinicians take a more aggressive approach in terms of both timing and pretreatment in patients with a clinical suspicion of a thrombotic lesion that might require ad hoc PCI. It could be ventured that pretreatment influences subsequent choice of revascularization strategy, tipping the balance in favor of PCI, but this is a mere hypothesis based on the available data. Third, patients were treated differently according to admission unit and access to a catheterization laboratory. Although the underlying issues are complex, there would appear to be room for improvement in these aspects of NSTEACS management. Finally, almost 10% of patients underwent coronary revascularization surgery. This rate is higher than previous rates described in other registry-based studies in Spain15–17 and clinical trials investigating P2Y12 inhibitors.12,14 Median time from coronary angiography to surgery was 8 days. This is too long in our opinion as excessive delays can potentially affect clinical outcomes. Long-term follow-up will help determine the therapeutic implications of different revascularization strategies in real-world settings.

Studies specifically designed to assess the impact of an early routine approach in patients with NSTEACS have not shown any clear benefits in terms of cardiovascular events.5–11 The TIMACS (Timing of Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndromes)6 and VERDICT (Very Early Versus Deferred Invasive Evaluation Using Computerized Tomography)5 trials did point to a possible association with ischemic risk, since a benefit was observed in subgroup analyses of patients with a GRACE score >140. Similar findings were reported for the CARDIOCHUS-HUSJ registry.17 Real-world hospital data from our study suggest that an early routine approach to the treatment of NSTEACS does not affect outcomes, even in high-risk patients. The only benefit observed was a shorter hospital stay. The delayed strategy, in turn, was associated with a very low incidence of in-hospital cardiovascular events and had a good safety profile in terms of bleeding, especially when combined with dual antiplatelet therapy. The delayed strategy with pretreatment was the most widely used strategy.

Although P2Y12 inhibitor pretreatment has not been found to have a benefit in NSTEACS based on recent clinical trial findings,12–14 and may even increase the risk of major bleeding, as shown in the ACCOAST trial,12 it is still widely used in Spain. Irrespective of these considerations, current evidence on the benefits of not pretreating patients scheduled to undergo coronary angiography is based on clinical trials with very short times to coronary angiography (hours rather than days).10,12,14 Therefore, the implications of delaying coronary angiography or revascularization surgery by several days in patients receiving aspirin only are not known. Our findings show that these patients were less likely to be anticoagulated before angiography. In the absence of dual antiplatelet therapy, we believe that anticoagulation should be standard practice in the context of routine radial access. Finally, we observed a notably low rate of prasugrel use (12.5% at discharge), even in patients without pretreatment, and a notably high rate of clopidogrel use (46% in pretreatment regimens and 37% at discharge). Assuming that the findings of the ISAR-REACT-5 trial14 largely prompted the modifications to the ESC guideline recommendations, analyzing coronary angiography timing and pretreatment strategies independently of antiplatelet therapy may influence prognostic evaluations.

LimitationsThe main limitations of this study are those inherent to any registry-based study, including an evident risk of bias affecting any causal inferences that may be drawn. Our conclusions must, therefore, be viewed as potential sources of hypotheses. In addition, because participation in the IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry is voluntary and local protocols on coronary angiography timing and pretreatment may vary, our findings cannot be extrapolated to Spanish hospitals as a whole. Likewise, because the registry specifically includes patients with confirmed NSTEACS, the findings are not applicable to patients presenting to an emergency department with chest pain or patients found not to have a culprit lesion despite an initial diagnosis of NSTEACS (10%-30% of all clinical trial patients).6,13 Despite these limitations, we believe that this national, prospective, multicenter study provides interesting and novel insights into clinical characteristics, management approaches, treatments, and outcomes in a large cohort of unselected consecutive patients with NSTEACS in Spain.

CONCLUSIONSIn Spain, just 13.6% of patients with NSTEACS undergoing coronary angiography receive an early invasive strategy without pretreatment. The overall incidence of cardiovascular events and major bleeding during hospitalization is low.

- –

Routine early coronary angiography, performed within 24 hours of admission, is recommended for patients with high-risk NSTEACS (elevated troponin, ECG changes, GRACE score>140).

- –

Pretreatment with a second antiplatelet agent is not recommended when early coronary angiography is planned. Ticagrelor and prasugrel are preferred over clopidogrel in the absence of contraindications; treatment with prasugrel may confer a benefit.

- –

Levels of compliance with current recommendations on early invasive and pretreatment strategies and choice of antiplatelet therapy are not known.

- –

In Spain, just 13.6% of patients with NSTEACS undergoing coronary angiography receive an early invasive strategy without pretreatment; 37.8% of patients underwent coronary angiography within 24 hours of admission and 30.3% did not receive dual antiplatelet pretreatment.

- –

Ticagrelor is the second most commonly used antiplatelet agent (49.7%), followed by clopidogrel (37.8%) and prasugrel (12.5%).

- –

Irrespective of coronary angiography timing and use of pretreatment, in-hospital cardiovascular events and major bleeding episodes are uncommon in patients with NSTEACS.

The authors guarantee that the following researchers are responsible for the data published in this study:

F. Díez-Delhoyo, G. Marañón, Madrid; M.T. López Lluva, Hospital Universitario de León; P. Cepas-Guillén, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona; A. Jurado-Román, Hospital La Paz, Madrid; P. Bazal-Chacón, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra; M. Negreira-Caamaño, Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real; I. Olavarri-Miguel, Hospital de Valcedilla, Santander; A. Elorriaga, Hospital de Basurto, Bilbao; R. Rivera López, Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada; D. Escribano, Hospital de San Juan de Alicante; P. Salinas, Hospital Clínico, Madrid; J. Vaquero-Luna, Hospital Txagorritxu, Vitoria; A. Prieto-Lobato, Hospital Universitario de Albacete; L. Pérez-Cebey, Hospital Universitario de A Coruña; A. Carrasquer, Hospital Joan XXIII, Tarragona; I. Llaóo, Hospital de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat; F. J. Torres Mezcúa, Hospital Universitario de Alicante Doctor Balmis; T. Giralt-Borrell, Hospital del Mar, Barcelona; M. Abellas, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid; S. García-Blas, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Valencia; L. Matute-Blanco, Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida; C. Robles-Gamboa, Hospital Universitario de Toledo; and P. Díez-Villanueva, Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid, on behalf of the IMPACT-TIMING-GO researchers.

FUNDINGThis is an unfunded study headed by the Young Cardiologists Group with scientific support from the Spanish Cardiology Society.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSStudy design, data collection and review, statistical analysis, and writing of manuscript: P. Díez-Villanueva, F. Díez-Delhoyo, and M.T. López-LLuva. All authors participated in the collection of data and revised and approved the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone to declare.

We are grateful to the Spanish Cardiology for supporting the Young Cardiologists Group and for fostering research among the younger members of our profession.