This article presents the 2023 activity report of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC).

MethodsAll interventional cardiology laboratories in Spain were invited to participate in an online survey. Data analysis was carried out by an external company and subsequently reviewed and presented by the members of the ACI-SEC board.

ResultsA total of 119 hospitals participated. The number of diagnostic studies decreased by 1.8%, while the number of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) showed a slight increase. There was a reduction in the number of stents used and an increase in the use of drug-coated balloons. The use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques remained stable. For the first time, data on PCI guided by intracoronary imaging was reported, showing a 10% usage rate in Spain. Techniques for plaque modification continued to grow. Primary PCI increased, becoming the predominant treatment for myocardial infarction (97%). Noncoronary structural procedures continued their upward trend. Notably, the number of left atrial appendage closures, patent foramen ovale closures, and tricuspid valve interventions grew in 2023. There was also a significant increase in interventions for acute pulmonary embolism.

ConclusionsThe 2023 Spanish cardiac catheterization and coronary intervention registry indicates a stabilization in coronary interventions, together with an increase in complexity. There was consistent growth in procedures for both valvular and nonvalvular structural heart diseases.

Keywords

The Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) has produced an annual report on interventional cardiology activities across Spain for more than 30 years.1–33

One of the main tasks of the ACI-SEC board of directors is to collect, filter, and disseminate the data submitted to the Spanish catheterization and interventional cardiology registry each year. While participation in the registry is voluntary, most public and private hospitals in Spain cooperate, as the annual reports are highly valued and eagerly anticipated. The reports provide an overview of the current state of interventional cardiology in Spain, facilitating regional comparisons and providing benchmark data for use by both hospitals and regions to identify key areas for improvement and resource optimization. One limitation is that the registry data are not audited. Nevertheless, with more than 3 decades of consistent data and widespread participation, the registry holds tremendous value. Each year, the variables to be submitted are updated to reflect changes and innovations in interventional cardiology.

In short, the Spanish catheterization and interventional cardiology registry is one of the most important initiatives of the ACI-SEC each year. It exemplifies the unity, collaborative spirit, and openness of interventional cardiology professionals throughout the country. The conclusions of the report are highly regarded by public administrators, private entities, the tech industry, and professionals involved in everyday clinical care. In this article, we present the 2023 (33rd) report on interventional cardiology activity in Spain, the results of which were presented at the ACI-SEC Congress held in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria on June 14, 2024.

METHODSThe Spanish ACI-SEC registry contains data on interventional cardiology activity undertaken by most of the country's public and private hospitals. Each hospital voluntarily submits information on its annual activities, resource use, and outcomes to an online database managed by an external company (pInvestiga). Each year, the variables are reviewed in depth and updated. None of the fields are mandatory, but special emphasis is placed on variables that are considered necessary or of particular value. The data are analyzed by pInvestiga with the assistance of an ACI-SEC board member. Any discrepancies or data flagged as questionable are refined and cross-checked. In such cases, the hospitals involved, and sometimes even the distribution companies, are contacted. Finally, the data are analyzed, compared with those of previous years, and disseminated in a publicly available annual report. To facilitate regional analyses and comparisons, data are indexed geographically according to the population of each autonomous community, as published on the National Institute of Statistics website.34 For the current report, the population of Spain was considered to be 48 085 361 inhabitants. Data are expressed as numbers and percentages. In the case of missing variables, percentages were calculated using only the number of centers that supplied data for the variables in question.

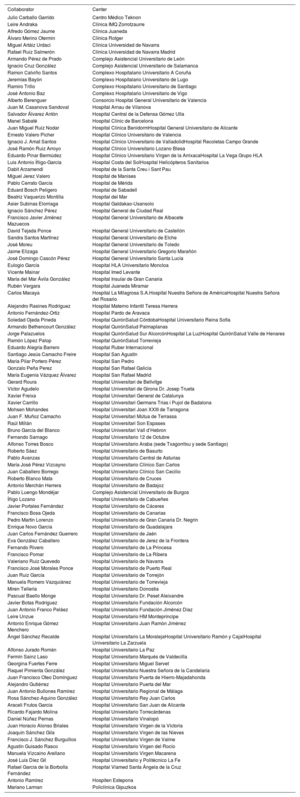

RESULTSInfrastructure and resourcesOf the 122 hospitals invited to participate in the registry in 2023, 199 (82 public and 37 private) submitted data. This represents a response rate of 97.5% and an increase of 2 public hospitals and 6 private hospitals compared with 2022. The completion rate was quite high, with 73 hospitals completing at least 50% of the variables and 72 completing at least 78% of the variables deemed necessary or particularly important.

As expected from the increase in hospitals, the number of catheterization laboratories also increased slightly, from 263 in 2022 to 267 in 2023. Of these, 154 were used exclusively for catheterization, 67 were shared, 30 were hybrid, and 16 were affiliated (overseen by another hospital with surgical backup). Of the 119 hospitals, 102 had on-call teams for round-the-clock care, and for the first time ever, hospitals were asked to report on after-hours on-call activities. They reported 30 795 infarction code activations, 19 734 (64%) of which resulted in percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). A considerable percentage of activations, however, resulted in other interventions, including diagnostic procedures without PCI for STEMI (9%) and diagnostic procedures or PCI for indications other than STEMI (24%). A number of new interventions were also reported, such as acute pulmonary embolism interventions (0.5%) and shock-assist device placement (2.5%).

The number of interventional cardiologists also rose in line with the increase in participating hospitals (542 vs 459 in 2022). The percentage of female interventional cardiologists remained practically unchanged, at 24.3%. There was an increase in the number of both registered nurses (793 vs 735) and diagnostic radiographers (110 vs 94).

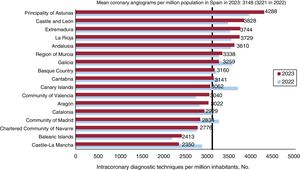

Diagnostic activityThe 2022 ACI-SEC report confirmed the return to pre-COVID-19 diagnostic activity levels. In 2023, however, there was a 1.8% reduction in the absolute number of diagnostic procedures (162 241), despite the increase in participating hospitals. The most common procedure was coronary angiography (93%), followed by right heart catheterization (4.4%) and endomyocardial biopsy (1%). The mean number of coronary angiograms per million population dropped from 3221 in 2022 to 3148 in 2023. The figures are shown by autonomous community in figure 1. The decrease in invasive diagnostic coronary procedures was accompanied by a 17.8% increase in coronary computed tomography angiograms (23 149 vs 19 657 in 2022).

Radial access continued to be the most popular access route for both diagnostic procedures (94.2%) and PCI (93.3%).

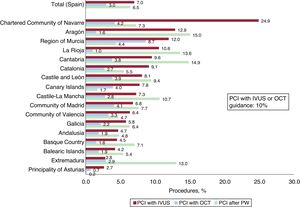

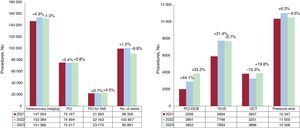

Intracoronary diagnostic techniquesThe progressive increase observed for intracoronary diagnostic techniques over the past 10 years seemed to level off in 2023 (figure 2), with a 4.5% reduction in pressure wire studies and, following a significant spike in 2022 (31.5%), a stabilization of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) increased by 19.8% following a 15.3% reduction in 2022 due to catheter supply chain disruptions for much of that year. Hospitals also submitted data on microcirculation and vasospasm studies for the second year running. The number of tests in both cases decreased, from 2384 to 1695 for microcirculation studies and from 2070 to 1541 for vasospasm studies.

The ratios of OCT/IVUS and pressure wire studies to PCIs are traditional indicators included in the ACI-SEC report. In 2023, the IVUS/OCT to PCI index increased to 15.3% (14.7% in 2022), while the pressure wire to PCI index decreased to 13.9% (14.7% in 2022). For the first time in the history of the registry, hospitals were asked to report on the actual use of these techniques during PCI. The information, supplied by 103 hospitals, showed that on average, 7% of PCIs in Spain are performed with IVUS guidance, 3% with OCT guidance, and 6.5% with pressure wire guidance. Intracoronary imaging was used in 10% of interventions. The regional distribution of the different techniques is shown in figure 3.

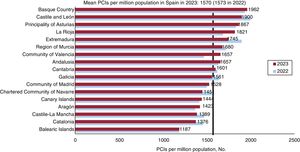

Percutaneous coronary interventionsThe number of PCIs performed in 2023 (75 517) was similar to postpandemic figures (74 894 in 2022 and 75 167 in 2021). Nonetheless, considering the slight increase in the general population, the number of PCIs per million population decreased slightly, continuing the trend observed in 2022 (1573 PCIs in 2023 vs 1570 in 2022 and 1586 in 2021). The distribution of PCIs by autonomous community, with Castile and León and the Basque Country maintaining the lead, is shown in figure 4. No significant differences were observed for anatomic locations, with a slight decrease in left main coronary artery interventions (7%) and a continuation of the slight upward trend in chronic total occlusion interventions (6.7% increase compared with 7.2% in 2022).

One of the most notable findings for 2023 was a reduction in stent placement, which was down from 100 857 procedures in 2022 (97 hospitals) to 90 881 in 2023 (91 hospitals). Most of the stents (98.7%) were drug-eluting devices. This notable reduction in stent placement, which can be partly explained by the fewer hospitals (including some high-volume centers) reporting this information, was accompanied by a significant increase in PCIs performed exclusively with drug-coated balloons (3852 in 2023 vs 2891 in 2022). This trend was already apparent in 2022, when PCIs with drug-coated balloons saw an increase of 885 procedures compared with 2021. Overall, the combined increase from 2021 to 2023 was 92%.

Most plaque modification procedures continued their upward trend, with a 23.8% rise in coronary intravascular lithotripsy procedures (from 1500 to 1857). The number of laser and rotational atherectomies was similar to that in 2022, as was the number of hospitals using these techniques. Most hospitals used speciality balloons (93%) and rotational atherectomies (88.8%); laser and orbital atherectomies were much less common (15% and 10.3%, respectively).

Assist devices were used in 1.9% of PCIs (2.1% in 2022); there was a slight decrease in the use of intra-aortic balloon pumps, confirming the trend of the previous 6 years. The upward trend previously observed for Impella devices (Abiomed, USA) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) continued. In the 6 years spanning 2018 to 2023, the use of intra-aortic balloon pumps fell from 1083 to 920, while that of Impella devices and ECMO increased from 149 to 352 and from 109 to 197, respectively.

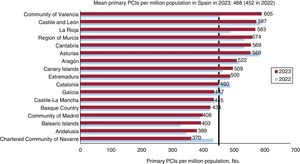

PCI for acute myocardial infarctionPCI for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) continued to gain traction in 2023 (up 4.5% from 2022 [23 170 vs 22 163]). Most of the procedures (97%) were primary interventions. Rescue and facilitated PCIs remained stable, with just 324 and 347 procedures each. Overall, the mean number of primary PCIs per million population increased from 442 in 2022 to 468 in 2023. The breakdown by autonomous community is shown in figure 5. The technical characteristics of the procedures were very similar to those reported in 2022, with radial access sites used in 92.9% of cases and thrombectomy in 33.2%; 7.2% of patients developed cardiogenic shock, and 3.4% required hemodynamic support. The use of cangrelor increased slightly, from 3.0% in 2022 to 3.7% in 2023. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors decreased slightly (from 17.8% to 16.8%).

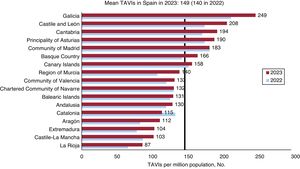

Structural interventionsAortic valve interventionsThe number of transcatheter aortic valve implantations (TAVIs) continued to rise in 2023, with hospitals reporting 7161 procedures compared with 6672 in 2022 (7.3% increase). The number of implantations per million population also rose, from 140 in 2022 to 149 in 2023. Galicia maintained a clear lead with 249 implants per million population. Significant increases compared with 2022 were observed in Castile and León, Cantabria, and Asturias (figure 6). A total of 245 valve-in-valve procedures (3.4% of all TAVIs) were reported (272 in 2022 and 197 in 2021). Other notable findings included 93 TAVIs for pure aortic regurgitation and 270 for bicuspid aortic valves. Almost one-third of the hospitals (31%) performed more than 100 TAVIs in 2023, 25% performed between 50 and 99, and 44% performed fewer than 50. There was a slight reduction in the proportion of patients at very high surgical risk (27.5% vs 35.8% in 2022) and those with a contraindication for surgery (27.5% vs 21.5%). The proportion of low-risk patients increased (15% vs 12.9%). Just 45% of TAVI patients in 2023 were older than 80 years, a significant drop compared with previous years (66.2% in 2021 and 65.5% in 2020; data unavailable for 2022). A percutaneous transfemoral access route was used in 96.2% of all TAVIs. Surgical transfemoral and axillary-subclavian routes were used in just 2.2% and 1.3% of cases, respectively. Alternative routes were uncommon (transaortic, 0.4%; transapical, 0.4%; percutaneous axillary-subclavian, 0.3%; and transcaval, 0.1%). The following valves were used: a) Edwards (Edwards Lifesciences, USA) (33.7% of procedures); b) Evolut (Medtronic, USA) (31.3%); c) Accurate Neo (Boston Scientific, USA) (15.3%); d) Navitor (Abbott Medical, USA) (11.9%); e) Allegra (Biosensors, Singapore) (3%); f) MyVal (Meril, India) (4.6%); and g) Hydra (Vascular Innovations Co. Ltd., Nonthaburi, Thailand) (0.2%).

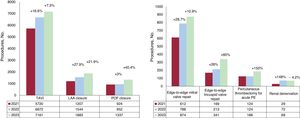

Mitral and tricuspid valve interventionsMitral valvuloplasty showed a slight increase in 2023, with 156 procedures compared with 143 in 2022. This number, however, remains substantially lower than that observed 5 years ago (> 200 procedures a year).

Edge-to-edge mitral repairs continued their upward trend, with a 10.9% increase (874 procedures vs 788 in 2022). The MitraClip device (Abbott Medical, USA) was used in 87% of edge-to-edge mitral repairs, while the Pascal device (Edwards Lifesciences, USA) was used in 13%. Just under half of the hospitals (47%) performed fewer than 10 annual repairs, 24% performed 10 to 19, 12% performed 20 to 29, and 17% performed more than 30. The regions with the highest volumes per million population were Asturias with 54 repairs, and Castile and León and Galicia with 29 each. Edge-to-edge mitral repairs were used to treat functional mitral regurgitation in 56% of cases, organic regurgitation in 27%, and functional and organic regurgitation in 17%. The hospitals also reported 28 percutaneous mitral valve repairs, half of which were valve-in-valve procedures.

Tricuspid valve repairs increased significantly from 231 in 2022 to 341 in 2023. Percutaneous edge-to-edge repairs accounted for 60% of the procedures (205 vs 109 in 2022); these were followed by bicaval valve implantations (22%) and annuloplasties with the Cardioband system (Edwards Lifesciences, USA) (7%).

Paravalvular leak closureThe year 2023 saw a decrease in both aortic (64 vs 70 in 2022) and mitral paravalvular leak closures (94 vs 110 in 2022).

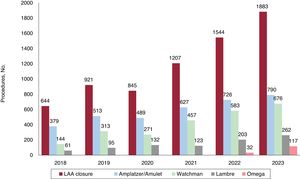

Nonvalvular structural interventionsOnce again, left atrial appendage closures were among the procedures that exhibited the greatest growth (figure 7), with 1883 procedures reported (22.9% increase [1544 in 2022]). Notable devices were Amulet (Abbott Vascular, USA), used in 790 procedures, Watchman FLX (Boston Scientific, USA) (676), Lambre (Lifetech Scientific, USA) (262), and Omega (Vascular Innovations, Thailand) (117).

There was a notable increase in nonvalvular structural interventions used to treat acute pulmonary embolism, with 186 cases (80 with specific devices) reported in 2023 (124 in 2022). The upward trend in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension interventions continued (144 vs 136 in 2022). Following a notable increase in 2022, renal denervations leveled off at 69 procedures (72 in 2022). Finally, there was an increase in the use of coronary sinus reducers (34 vs 12 in 2022).

Adult congenital heart disease interventionsSince 2022, information on congenital heart disease interventions has been compiled in a separate document produced in conjunction with the Working Group on Hemodynamics of the Spanish Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Congenital Heart Diseases.35 Of note in 2023, there was a 40.4% increase in patent foramen ovale repairs, with 1337 procedures reported compared with 953 in 2022. Most of the 2023 procedures were performed using double-disc devices (1298, 97%); just 39 were performed with suture-based devices. Finally, there were 402 atrial septal defect repairs (351 in 2022) and 82 coarctation repairs (73 in 2022).

DiscussionThe 2023 activity report of the ACI-SEC Spanish catheterization and interventional cardiology registry revealed several noteworthy findings. First, there was a slight decrease in invasive diagnostic procedures and an increase in noninvasive diagnostic procedures (coronary computed tomography angiography). Second, the use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques leveled off after several years of growth. Third, the number of PCIs remained largely unchanged, although this procedure is increasingly used to treat AMI, with primary PCI firmly established as the main strategy in Spain. Fourth, stent placement decreased alongside a continued rise in the use of drug-coated balloons. Fifth, there was a consistent increase in plaque modification techniques, despite the plateauing observed for PCIs. Finally, structural interventions continued to grow in all areas, particularly for tricuspid valve repairs, left atrial appendage closures, patent foramen ovale closures, and acute pulmonary embolism interventions (figure 8 and figure 9).

Consistent with the trends observed in previous years, interventional cardiology took on a new shape in 2023, showing significant growth in structural interventions and signs of plateauing in coronary artery disease interventions. Factors that may have contributed to the slowdown in the latter case include the emergence of noninvasive diagnostic techniques and the publication of studies questioning the true benefits of revascularization in patients with chronic coronary syndrome or ventricular dysfunction.36,37 Several findings, including the slight decrease in diagnostic procedures and the general leveling off of PCIs (albeit with increases noted for patients with acute coronary syndrome), may reflect a more selective use of invasive treatments for patients with stable, chronic coronary artery disease.

The growing use of plaque modification techniques reflects an increase in complex cases and the growing importance attached to adequate lesion preparation by interventional cardiologists. The low use of intracoronary imaging techniques to guide PCIs (10%), however, is striking, particularly considering the growing body of scientific evidence supporting these techniques.38–41 The considerable differences in uptake between regions are also noteworthy (figure 3). Although 2023 has frequently been referred to as “the year of intracoronary imaging,” this trend is not yet reflected in the Spanish catheterization and interventional cardiology registry. In the coming years, however, we can probably expect greater use of intracoronary diagnostic procedures as a means of optimizing diagnostic and coronary intervention outcomes.

One of the most notable findings of the 2023 report is the reduction in stent usage despite a similar number of PCIs. We believe there are 2 main reasons for this: first, the decrease in the number of hospitals reporting data on stent usage and second, the undeniable upswing in the use of drug-coated balloons. The number of PCIs performed exclusively with drug-coated balloons has doubled in 2 years. The growing interest in these devices, aligned with the “leave nothing behind” strategy, reflects a shift towards an increasing use of implant-free approaches in indications beyond in-stent restenosis, small vessels, and side branches.

Myocardial infarction interventions are clearly on the rise in Spain, with year-on-year increases in practically all the country's autonomous communities and a clear predominance of primary PCI for reperfusion, with fibrinolysis playing a very secondary role. Notably, a significant proportion of infarction code alerts corresponded to indications other than myocardial infarction, and the registry also showed an increasing use of invasive techniques to manage acute pulmonary embolism and mechanical assist devices for patients in cardiogenic shock. These findings may be valuable for planning and optimizing resources required for the various STEMI code programs in Spain, which vary significantly from region to region.42

Structural interventions continued to grow steadily and relentlessly across techniques, with particularly notable increases in left atrial appendage and patent foramen ovale closures and tricuspid valve repairs. The long-term prognostic benefits of percutaneous edge-to-edge mitral repair, highlighted in 2023,43 probably partly explain the growing popularity of this technique. Similarly, the growing use of TAVI in ever younger patients likely reflects evidence supporting its benefits in low-risk patients.44 The registry findings show that the proportion of patients aged >80 years undergoing TAVI fell from 65% in 2021 to 45% in 2023. Overall, the 2023 ACI-SEC report shows that a significant proportion of interventional cardiology activity has shifted towards addressing noncoronary structural heart disease, a field that appears to be expanding annually to cover more indications and patients who could benefit from these interventions.

The final finding of note in the 203 ACI-SEC report is the increase in acute pulmonary embolism interventions, almost half of which involved the use of dedicated devices. Although evidence in this field is still limited, there is clear interest and growth, likely linked to the high incidence and significant morbidity and mortality associated with pulmonary embolism.45

LimitationsThe main limitation of the registry is that participation is voluntary and the data are not audited.

CONCLUSIONSThe 33rd report on the ACI-SEC Spanish cardiac catheterization and coronary intervention registry reflects a stable landscape for coronary interventions in Spain, characterized by a trend toward reduced stent placement, increased use of drug-coated balloons, and sustained growth in plaque modification techniques. Finally, structural interventions continued their unstoppable growth across nearly all techniques.

FUNDINGThis study received no funding.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll the authors contributed to writing and critically reviewing this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTD. Arzamendi has performed consultancy work and is a proctor for Abbott and Edwards. J. Martín-Moreiras is a proctor for Boston Scientific and World Medica. T. Bastante and A.B. Cid Álvarez have no conflicts of interest.

| Collaborator | Center |

|---|---|

| Julio Carballo Garrido | Centro Médico Teknon |

| Leire Andraka | Clínica IMQ Zorrotzaurre |

| Alfredo Gómez Jaume | Clínica Juaneda |

| Álvaro Merino Otermin | Clínica Rotger |

| Miguel Artáiz Urdaci | Clínica Universidad de Navarra |

| Rafael Ruiz Salmerón | Clínica Universidad de Navarra Madrid |

| Armando Pérez de Prado | Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León |

| Ignacio Cruz González | Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca |

| Ramon Calviño Santos | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña |

| Jeremías Bayón | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Lugo |

| Ramiro Trillo | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago |

| José Antonio Baz | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo |

| Alberto Berenguer | Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia |

| Juan M. Casanova Sandoval | Hospital Arnau de Vilanova |

| Salvador Álvarez Antón | Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla |

| Manel Sabaté | Hospital Clínic de Barcelona |

| Juan Miguel Ruiz Nodar | Hospital Clínica BenidormHospital General Universitario de Alicante |

| Ernesto Valero Picher | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia |

| Ignacio J. Amat Santos | Hospital Clínico Universitario de ValladolidHospital Recoletas Campo Grande |

| José Ramón Ruiz Arroyo | Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa |

| Eduardo Pinar Bermúdez | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la ArrixacaHospital La Vega Grupo HLA |

| Luis Antonio Íñigo-García | Hospital Costa del SolHospital Helicópteros Sanitarios |

| Dabit Arzamendi | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau |

| Miguel Jerez Valero | Hospital de Manises |

| Pablo Cerrato García | Hospital de Mérida |

| Eduard Bosch Peligero | Hospital de Sabadell |

| Beatriz Vaquerizo Montilla | Hospital del Mar |

| Asier Subinas Elorriaga | Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo |

| Ignacio Sánchez Pérez | Hospital General de Ciudad Real |

| Francisco Javier Jiménez Mazuecos | Hospital General Universitario de Albacete |

| David Tejada Ponce | Hospital General Universitario de Castellón |

| Sandra Santos Martínez | Hospital General Universitario de Elche |

| José Moreu | Hospital General Universitario de Toledo |

| Jaime Elízaga | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón |

| José Domingo Cascón Pérez | Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía |

| Eulogio García | Hospital HLA Universitario Moncloa |

| Vicente Mainar | Hospital Imed Levante |

| María del Mar Ávila González | Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria |

| Rubén Vergara | Hospital Juaneda Miramar |

| Carlos Macaya | Hospital La Milagrosa S.A.Hospital Nuestra Señora de AméricaHospital Nuestra Señora del Rosario |

| Alejandro Rasines Rodríguez | Hospital Materno Infantil Teresa Herrera |

| Antonio Fernández-Ortiz | Hospital Pardo de Aravaca |

| Soledad Ojeda Pineda | Hospital QuirónSalud CórdobaHospital Universitario Reina Sofía |

| Armando Bethencourt González | Hospital QuirónSalud Palmaplanas |

| Jorge Palazuelos | Hospital QuirónSalud Sur AlcorcónHospital La LuzHospital QuirónSalud Valle de Henares |

| Ramón López Palop | Hospital QuirónSalud Torrevieja |

| Eduardo Alegría Barrero | Hospital Ruber Internacional |

| Santiago Jesús Camacho Freire | Hospital San Agustín |

| María Pilar Portero Pérez | Hospital San Pedro |

| Gonzalo Peña Perez | Hospital San Rafael Galicia |

| María Eugenia Vázquez Álvarez | Hospital San Rafael Madrid |

| Gerard Roura | Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge |

| Víctor Agudelo | Hospital Universitari de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta |

| Xavier Freixa | Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya |

| Xavier Carrillo | Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol de Badalona |

| Mohsen Mohandes | Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona |

| Juan F. Muñoz Camacho | Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa |

| Raúl Millán | Hospital Universitari Son Espases |

| Bruno García del Blanco | Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron |

| Fernando Sarnago | Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre |

| Alfonso Torres Bosco | Hospital Universitario Araba (sede Txagorritxu y sede Santiago) |

| Roberto Sáez | Hospital Universitario de Basurto |

| Pablo Avanzas | Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias |

| María José Pérez Vizcayno | Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos |

| Juan Caballero Borrego | Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio |

| Roberto Blanco Mata | Hospital Universitario de Cruces |

| Antonio Merchán Herrera | Hospital Universitario de Badajoz |

| Pablo Luengo Mondéjar | Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Burgos |

| Íñigo Lozano | Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes |

| Javier Portales Fernández | Hospital Universitario de Cáceres |

| Francisco Bosa Ojeda | Hospital Universitario de Canarias |

| Pedro Martín Lorenzo | Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín |

| Enrique Novo García | Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara |

| Juan Carlos Fernández Guerrero | Hospital Universitario de Jaén |

| Eva González Caballero | Hospital Universitario de Jerez de la Frontera |

| Fernando Rivero | Hospital Universitario de La Princesa |

| Francisco Pomar | Hospital Universitario de La Ribera |

| Valeriano Ruiz Quevedo | Hospital Universitario de Navarra |

| Francisco José Morales Ponce | Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real |

| Juan Ruiz García | Hospital Universitario de Torrejón |

| Manuela Romero Vazquiánez | Hospital Universitario de Torrevieja |

| Miren Tellería | Hospital Universitario Donostia |

| Pascual Baello Monge | Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset Aleixandre |

| Javier Botas Rodríguez | Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón |

| Juan Antonio Franco Peláez | Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz |

| Leire Unzue | Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe |

| Antonio Enrique Gómez Menchero | Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez |

| Ángel Sánchez Recalde | Hospital Universitario La MoralejaHospital Universitario Ramón y CajalHospital Universitario La Zarzuela |

| Alfonso Jurado Román | Hospital Universitario La Paz |

| Fermín Sainz Laso | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla |

| Georgina Fuertes Ferre | Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet |

| Raquel Pimienta González | Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria |

| Juan Francisco Oteo Domínguez | Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda |

| Alejandro Gutiérrez | Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar |

| Juan Antonio Bullones Ramírez | Hospital Universitario Regional de Málaga |

| Rosa Sánchez-Aquino González | Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos |

| Araceli Frutos Garcia | Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante |

| Ricardo Fajardo Molina | Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas |

| Daniel Núñez Pernas | Hospital Universitario Vinalopó |

| Juan Horacio Alonso Briales | Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria |

| Joaquín Sánchez Gila | Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves |

| Francisco J. Sánchez Burguillos | Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme |

| Agustín Guisado Rasco | Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío |

| Manuela Vizcaino Arellano | Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena |

| José Luis Díez Gil | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe |

| Rafael García de la Borbolla Fernández | Hospital Viamed Santa Ángela de la Cruz |

| Antonio Ramírez | Hospiten Estepona |

| Mariano Larman | Policlínica Gipuzkoa |