INTRODUCTION

Following the creation of the Banco Nacional de Datos de Marcapasos (National Pacemaker Data Bank, BNDM) in Spain,1 the first official report was published in the Revista Española de Cardiología in 19972 to report on trends observed since 1994. Since that time, information has been regularly published on the most relevant aspects of cardiac pacing in Spain.3-6 Detailed information has been freely available at the website of the Cardiac Pacing Section (www.marcapasossec.org) since 1999.

The present work reports the data for the year 2006 and discusses a number of developments that have taken place in recent years.

METHODS

The database was redesigned in Access some years ago and a new computer application was written to use the database. As a result, the trends observed in some areas vary over the years of follow-up.

The information processed consisted only of data listed in the various fields of the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card,2 sent to the registry by physicians who implant pacemakers at the various hospitals or by the companies as set forth in the current legislation.5,6 Hardcopy and digital information was accepted, including information presented in in-house database formats used by the sites, regardless of design, with the required protection measures. Specific measures are provided by the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Stimulation.

In 2006 information was received from the 105 hospitals and clinics listed at the end of this article according to autonomous community.

As on previous occasions, the total number of pacemakers purchased in 2006 was obtained from the different businesses operating in this sector in Spain. This information was also sent to Eucomed. Nevertheless, a comparison of the 2 sets of data always shows some variation that is hard to interpret (year-end close in different months of the calendar year, etc).

The data used to analyze the various aspects of the Spanish population for the year mentioned are taken from the report periodically issued and updated by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (National Institute of Statistics, INE) (available at: www.ine.es). The BNDM also provides general data to the European Pacemaker Registry, which has information on cardiac pacing in Spain, as well as comparative data from the various European countries since 1994.7

RESULTS

Number of Pacemakers Implanted Per Million Inhabitants. Analyzed Sample

In 2006 the population of Spain was 44.7 million inhabitants, with 49.4% males and 50.6% females (INE figures). According to data reported to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry, 29 670 pacemakers were used in 2006, of which 474 were cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices with no defibrillator. As in other years, some differences were seen with regard to the figures reported to Eucomed, which were 29 242 and 501 respectively. Based on these considerations, the number of pacemaker generators used per million inhabitants was between 668.6 and 654.1 according to the figures cited above we considered, and that of CRT devices, between 10.6 and 11.2.

In 2006, 10 401 pacemaker implant or generator replacement cards were received by the BNDM registry from 105 hospitals, a figure corresponding to 35% of all pacemakers, according to sales data provided to the BNDM by the different businesses operating in the sector. An additional 1245 units over 2005 were implanted, an increase of 13.6%.

Population Age and Sex

The mean age of patients who received a pacemaker for the first time (hereinafter, first implants) in 2006 was 75.8 years. A slight, gradual increase has been observed every year, possibly caused by a shift due to population ageing. The mean age of the male patients was 75.1 years, somewhat less than that of the female patients (76.7), a finding also observed in all other years analyzed.

The largest number of first implants was received by patients in their 70s (39.2%), followed by those in their 80s (35.2%). This shows that, in the majority of cases, the need for an implant was usually associated with a degenerative problem.

There was a higher incidence of implants in male patients, who accounted for 57.5% of the total, a trend seen in both first implants (58.1%) and replacements (55.1%), even though the female population is larger (INE statistics). This ratio held steady throughout the entire period for which data are available (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentages of men and women who received their first pacemaker, 1994-2006.

An analysis of implant distribution according to age group and sex showed that the higher incidence in male patients was virtually the same in all age groups, except for patients above age 90, consistent with the fact that the female population of this last group was twice that of men, due to greater longevity (Figure 2) (available at: http://www.ine.es/inebase/cgi/axi).

Figure 2. Implant distribution according to age group and sex. W indicates women (percentage of age group); T, percentage of total units implanted in 2006; M, men (percentage of age group).

A comparison of electrocardiographic indications showed that the incidence between men and women was almost the same in the sick sinus syndrome (SSS) group at a ratio of 1:1. However, a higher incidence was seen among male patients for all other indications, for instance, intraventricular conduction disturbances (IVCD) with a male to female ratio of 2:1, atrioventricular blocks (AVB), 1.4, and atrial fibrillation or flutter (AF/FL) accompanied by bradycardia or AVB, 1.4. These results are similar to those observed in the last 2 years studied.

Type of Activity. First Implant. Generator and/or Electrode Replacements

The patients who received a pacemaker system for the first time accounted for 75.6% whereas generator replacements were 24.4% of all procedures reported. This was the first year analyzed since 1999 in which the proportion of generator-related procedures decreased in comparison to first implants (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Trend observed in the ratio of first implants and replacements.

The reasons listed for generator explant or replacement were mainly battery depletion (90.9%), premature battery depletion (1.1%), and major or minor generator defects (0.2%). Details on the other reasons are shown in Figure 4, which also shows that infection or erosion accounted for 2.4% of all units removed.

Figure 4. Indications for generator replacements or explants, expressed as a percentage.

The replacement of insulated leads represented a small percentage of all activity recorded (whether for lead deterioration or defects) at 0.1%. The reasons most commonly implicated in removals of electrode leads were infection or ulceration (48.7%), elective replacements (10.8%), lead rupture (8.1%), and insulation failure (2.7%), among others.

The implantation of a new electrode lead associated with simultaneous generator replacement accounted for 1.5% of all procedures carried out, whether for a change or upgrade in the pacing mode, elective for deterioration of the electrical conditions of the lead, or for an injury caused by the lead during the actual replacement procedure.

Symptoms

The most significant clinical symptoms reported by patients (secondary to rhythm or conduction disturbances that led to the condition) were as follows, in order from more to less common: syncope (42.1%), dizziness (27.4%), dyspnea ,or signs of heart failure (12.3%), and bradycardia (11.4%). Implants in asymptomatic patients or prophylactic implants accounted for 2.5%, and resuscitated sudden death, 0.1%, of all indications.

Etiology

Hypothetical degeneration or fibrosis of the conduction system of the heart was the cause most commonly reported as the condition that required implantation (46.3%), followed by unknown etiology (33.1%). Atrioventricular node ablation accounted for 1.3%. The total for the therapeutic-iatrogenic group is 2.7%. Among the neuromediated syndromes, carotid sinus syndrome is the one that accounts for most indications (1.2% of the total), whereas malignant vasovagal syndrome was 0.2%.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy as an etiology was present in only 0.4% of indications; of these, 18% had no electrocardiographic abnormalities or manifestations indicative of implant (eg, were coded for normal sinus rhythm). Therefore, it is assumed that the indication of drug-resistant hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, still under debate, was the most probable reason for implantation. This was estimated at a total of 25 units in 2006, although some decrease over the previous year was observed.

Electrocardiographic Abnormalities

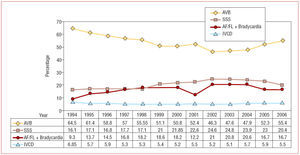

The electrocardiographic abnormalities or alterations in which implantation was indicated included atrioventricular conduction disturbances, which was the most common (55.4%), followed by SSS in all its manifestations (including AF/FL with bradycardia) (36.8%). Intraventricular conduction disturbances were 5.5%. Details for the subgroups are indicated in Figure 5, as well as the trends since 1994. This figure shows there has been some increase in AVB indications in the past year, although the indication for IVCDs has remained stable over all years analyzed (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Electrocardiographic indications for implantation in 2006 and total percentage of sick sinus syndrome (SSS) and atrioventricular block (AVB), associating patients with atrial fibrillation or flutter with slow ventricular response (AF/FL) and bradycardia, or block (card codes E6 and C8, respectively). AF indicates atrial fibrillation; IVCD, intraventricular conduction disturbances.

Figure 6. Trend data (%) for the main electrocardiographic abnormalities before implantation, 1994-2006. AVB indicates atrioventricular block; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; AF/FL, atrial fibrillation or flutter with slow ventricular response; IVCD, intraventricular conduction disturbances.

Implanted Lead Polarity and Fixation System

Bipolarity has gained ground in permanent cardiac pacing in recent years, and almost all leads implanted are bipolar (>99%). According to location, the atrial site accounted for 99.8% and ventricular, 99.5%.

Only a few unipolar leads were used as follows: 50% ventricular, implanted by endocavitary approach, 33.8% epicardial through the coronary sinus, 9.6% epicardial in cardiac surgery procedures, and 6.4% endocavitary in atrium.

The active-fixation system for the leads continued to gain acceptance in both chambers, with a gradual increase observed in use, and accounted for 35.2% of the total in 2006. These represented more than half (52.2%) of those used in the atrial position and 28.1% in the ventricular position (Figure 7). The increase may be due to various causes, such as the appropriate acute and chronic thresholds currently obtained from the new active-fixation electrodes, practically similar to those of passive fixation. Additionally, any explant needed is readily performed, since the entire body is isodiametric and has the advantage over passive type that it allows implantation at nonconventional places for pacing in alternative sites in both the atrium and the ventricle (such as low atrial septum, right ventricular outflow tract, His area, etc), an approach advocated by an increasing number of practitioners.

Figure 7. Active-fixation system for electrode leads. Trends for atrial and ventricular sites, for years with available data (2002-2006).

Pacing Modes

General

As a whole, single-chamber pacing (atrial or ventricular) accounted for a total of 42.5% and dual-chamber pacing (whether DDD/R or VDD/R), 57.4%. Atrial pacing alone was no more than 1.1% of all implants. These data show a 20.5% shift in the pacing mode recommended, according to the indications established in the various clinical guidelines,8-10 among all conditions and indications that led to implantation (the percentage of patients with persistent AF/FL, whether with associated AV block or bradycardia, was 20.8% and the total for isolated ventricular pacing, VVI/R, 41.3%). One of the factors that most influenced mode selection was age.

The association of some kind of sensor for proper frequency response was 78.2% of all generators used and showed a steady figure compared to the previous year.

According to the data reported to the registry, pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy was 1.6% of all first implants and 0.9% of all replacements; the latter corresponded to selective upgrades or taking advantage of battery depletion. These figures refer only to units implanted with no defibrillator, in which a significant increase was observed after stabilization in the previous year: 474 generators were used, according to BNDM information (some increase in 2006 in both number and percentage of total units), compared to 407 units reported in 2005. These correspond to sample percentages of 1.3% in 2004, 1.3% in 2005, and 1.5% in 2006, of all generators. CRT devices with a defibrillator experienced a higher increase with figures twice those observed 2 years ago, for a total of 848 in 2006, 703 in 2005, and 473 in 2004 (Eucomed data).

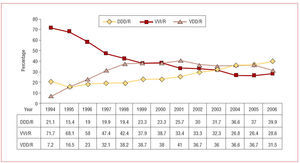

AVB Pacing

Pacing in AVB cases among patients who had sinus rhythm was 39.9% for DDD/R, followed by 31.4% for VDD/R. The total for dual-chamber pacing or pacing with atrial detection was 71.3%. The trend observed in the past 2 years showed similar percentages for VVD and DDD, but has shifted, now showing an increase in the DDD/R mode compared to a decrease in VDD/R.

A total of 28.6% did not use the mode that had been recommended,8-10 because atrial asynchrony was not maintained and VVI/R pacing was used. The percentage of single-chamber ventricular pacing showed a small upturn with regard to the trends in the previous years, which had shown a progressive decrease (Figure 8).

Figure 8.Trends for the various pacing modes used in atrioventricular block, excluding patients with persistent atrial fibrillation (card code C8), 1994-2006.

Age continued to be a clearly influential factor in pacing mode selection, with a substantial difference among the age groups for which trends have assessed since 2001. In 2006 the VVI/R mode was chosen more often in both of the age groups considered and VDD/R less often; DDD/R mode showed some increase in both groups (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9. Pacing modes in atrioventricular block according to age group (80 years or older and younger than 80), excluding patients with persistent atrial fibrillation or flutter, 2006.

Figure 10. Trends (expressed as a %) for VDD/R pacing in atrioventricular blocks, excluding patients with persistent atrial fibrillation or flutter, according to age group, for the past 6 years.

If we compare pacing among patients according to the grade of block, separating first-degree and second-degree AVBs from third-degree AVBs, we observe that this was generally done more in keeping with the recommended mode for the first group (VVI/R, 24.9% and 30.1%; DDD/R, 44.2% and 38.1%, and VDD/R, 30.7% and 31.7%) in both groups mentioned.

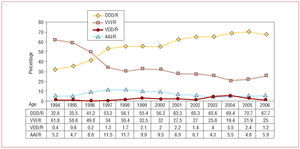

Pacing in Sick Sinus Syndrome

As on previous occasions, although the pacemaker patient identification card for patients with SSS were coded as E6 (atrial fibrillation or flutter with bradycardia), the information was processed after excluding this group, in order to avoid any potential interference in the suitability of pacing mode selection in this condition. This E6 subgroup corresponds to patients with persistent atrial arrhythmia, in which the mode used should, in our understanding, only be VVI/R. This did not happen in all cases, however: 6% had DDD/R pacing and a few had AAI/R (0.1%), assumed to be patients with paroxysmal or nonpersistent atrial arrhythmia or where the intention was to revert to sinus rhythm. These patients should perhaps be included in other SSS subgroups.

In SSS, the pacing mode was usually DDD/R (67.7%) or AAI/R (5.9%), for a total of 73.7% of all modes capable of atrial pacing and detection, the basis for pacing in SSS. The trends showed some decrease in DDD pacing (3%) that was not offset by the 1% increase in AAI/R when compared to the previous year. Some increase was also observed in single-chamber ventricular pacing, with a total of 25%. A few patients still have VDD/R pacing (1.2%), even though this has decreased. Neither of these pacing modes is actually indicated in SSS with sinus rhythm (and both are also potentially symptomatic due to possible retrograde conduction). The gradual improvement in pacing quality in SSS seen during the years of follow-up was not seen in 2006 (Figure 11).

Figure 11.Trends (expressed as a %) for pacing modes in sick sinus syndrome, excluding patients with persistent atrial tachyarrhythmia (card code E6), 1994-2006.

A comparison of the 2 age groups (using a cut-off point of 80 years) showed a substantial difference in the percentage of VVI/R pacing: 40.3% in patients 80 years of age or older and 17.5% in younger patients. This was due to less frequent use of dual-chamber pacing, DDD/R. The figures were practically the same for single-chamber atrial pacing and VDD/R in both groups (Figure 12). This similarity in the AAI/R mode and the differences in the use of DDD/R (Figure 13) were still present and showing a downward trend, but almost constant over the years for which the trends were analyzed (2001-2006).

Figure 12. Distribution for pacing modes in sick sinus syndrome, according to age group, 2006.

Figure 13. Trends (expressed as a %) of DDD/R pacing in sick sinus syndrome, according to age group, excluding patients with persistent atrial fibrillation or flutter, for the past 6 years.

Pacing in Intraventricular Conduction Disturbances

Pacing capable of maintaining atrial asynchrony is almost 70%, the majority DDD/R (50.5%), followed by VDD (18.9%). VVI/R pacing (30.5%) also experienced some increase over 2005 in this indication, thus confirming the upward trend for the second consecutive year (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Pacing modes in intraventricular conduction disturbances, for 2006 and with available trend data.

As in the electrocardiographic indications above, an analysis of modes for the 2 age groups showed that the choice of mode was a determining factor, with a proportion of 47.7% for VVI/R in patients 80 years or older versus 17.9% in younger patients.

The use of pacemakers for CRT in this IVCD group was 8%, also with a clear difference between age subgroups, accounting for only 1.5% of those 80 years of age or older and 13.1% of younger patients.

Data Quality

All data analyzed in the above sections have been taken from the cards received at the registry in 2006, 35% of all pacemakers implanted in Spain that year, or a 3% increase over the total for the previous year. Nevertheless, some of the following sections had not been properly completed or filled out on the cards received: age (8%), sex (11% in first implants, 12% in replacements), symptoms (22% in first implants, 42% in replacements), etiology (44% in first implants, 51% in replacements), and ECG indications (20% in first implants, 27% in replacements).

CONCLUSIONS

Over the years analyzed, men continued to account for a higher percentage of pacemaker implants, even though there were fewer men than women in the general population, and the difference continued to be similar with no clear trend toward greater balance. According to age group, only the group over age 90 had fewer men than women, due to the longevity of the latter. Furthermore, the age at first implant was slightly lower in men than women. In the various electrocardiographic indications, the number of men was also higher. The only exception was SSS, in which the incidence was practically the same in both sexes. The highest number of indications was seen among patients in their 70s, followed by those in their 80s.

Replacements represented a quarter of all generators implanted.

Bipolar leads accounted for the vast majority of all leads. The number of active-fixation system for leads continued to rise and now represented 35% of the total number. In the atrial position, the figure was 52%.

AVBs accounted for a higher number of indications than SSS.

In general, DDD/R pacing held steady in recent years at around 40% of the total.

In 2006 there was a noticeable increase in VVI/R pacing without a simultaneous increase in the situations that would theoretically indicate this kind of pacing (atrial tachyarrhythmia with block or bradycardia), coinciding with some decrease in the use of the VDD mode. However, although the use of the VDD mode in Spain has been decreasing since 2001, more than 5250 units were implanted in 2006. It was calculated that over 20% of all patients with VVI/R pacing for the various indications could use more appropriate pacing modes (DDD/R, VDD/R, AAI/R). AAI/R pacing continues to be underused.

Age has been shown to be a determining factor for the adaptation or selection of the pacing mode.

The percentage of pacemakers for CRT not associated with a defibrillator has risen to 1.6% of the total number of first implants, but to a lesser extent than units with a defibrillator.

The number of hospital sites that sent information and the number of pacemaker patient identification cards increased significantly and accounted for a higher percentage of the theoretical total number of cards. This was not true of the quality or completion of the data sent to the registry and there was a high percentage with incomplete data, particularly in the case of cards for replacements.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To Gonzalo Justes Toha, IT at the Spanish Society of Cardiology, for his invaluable assistance with the tools and applications required to use the registry.

To Pilar González Pérez, R.N., and Brígida Martínez Noriega, R.N., who bring extensive experience and dedication to the area of cardiac pacing, for their key role in maintaining the pacemaker registry, as this study would have been impossible without their help.

To all medical staff at the hospitals who participated directly or indirectly by filling out or sending pacemaker patient identification cards, and to the staff at the various pacemaker businesses, all of whom were sources of the information processed.

Hospitals From Which Data Were Received in 2006

Andalusia: Clínica de Fátima, Clínica Parque San Antonio, Complejo Hospitalario Virgen Macarena, Hospital Costa del Sol, Hospital de La Línea, Hospital Infanta Elena, Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Hospital Punta Europa, Hospital San Cecilio, Hospital Xanit, Servicio Andaluz de Salud de Cádiz

Aragon: Clínica Montpelier, Hospital General de Teruel Obispo Polanco, Hospital Miguel Servet, Hospital Militar de Zaragoza

Canary Islands: Clínica la Colina, Clínica Santa Cruz, Hospital de La Candelaria, Hospital Dr. Negrín, Hospital General de La Palma, Hospital General de Lanzarote, Hospital Insular, Hospital Universitario de Canarias

Castile-León: Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca, Hospital de León, Hospital del Bierzo, Hospital del Río Hortega, Hospital General de Segovia, Hospital General del Insalud de Soria, Hospital General Virgen de la Concha, Hospital General Yagüe, Hospital Universitario de Valladolid

Castile-La Mancha: Clínica Marazuela, Hospital Alarcos, Hospital General Virgen de La Luz, Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado, Hospital Virgen de la Salud

Catalonia: Centro Quirúrgico San Jorge, Clínica Tres Torres, Complejo Hospitalario Parc Taulí, Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona, Hospital de Bellvitge Prínceps d'Astúries, Hospital de Tortosa Virgen de la Cinta, Hospital del Mar, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona, Hospital de Terrassa, Hospital Sant Camilo, Hospital Sant Joan, Hospital Sant Pau i Santa Tecla

Ceuta: Hospital de la Cruz Roja, Ingesa

Extremadura: Hospital Comarcal de Zafra, Hospital San Pedro Alcántara, Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina

Galicia: Complejo Hospitalario Arquitecto Marcide, Complejo Hospitalario Juan Canalejo, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Complejo Hospitalario Xeral Lugo-Calde, Complejo Hospitalario Xeral-Cies, Hospital do Meixoeiro, Hospital de Montecelo

Balearic Islands: Complejo Asistencial Son Dureta, Hospital Son Llàtzer, Hospital Verge del Toro

Madrid: Clínica la Milagrosa, Clínica Nuestra Señora de América, Clínica Virgen del Mar, Fundación Hospital Alcorcón, Hospital 12 de Octubre, Hospital de Fuenlabrada, Hospital de Móstoles, Hospital la Paz, Hospital Príncipe de Asturias, Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Hospital Severo Ochoa, Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Hospital Universitario San Carlos

Murcia: Hospital General Santa María del Rosell, Hospital Morales Meseguer, Hospital Rafael Méndez

Navarra: Clínica San Miguel, Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Hospital de Navarra

Basque Country: Clínica Vicente de San Sebastián, Clínica Virgen Blanca de Bilbao, Clínica Virgen del Pilar, Hospital de Cruces, Hospital de Guipúzcoa Donostia, Hospital Santiago Apóstol, Hospital Txagorritxu, Policlínica de Guipúzcoa S.L.

Principado de Asturias: Fundación Hospital de Jove, Hospital Central de Asturias, Hospital de Cabueñes, Hospital Valle del Nalón

La Rioja: Hospital San Millán

Valencia: Clínica Benidorm, Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Hospital Universitario La Fe, Hospital de la Vega Baja

ABBREVIATIONS

AF/FL: atrial fibrillation or flutter

AVB: atrioventricular block

BNDM: Banco Nacional de Datos de Marcapasos (National Pacemaker Data Bank)

CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy

IVCD: intraventricular conduction disturbances

SSS: sick sinus syndrome

Correspondence: Dr. R. Coma Samartín

Arturo Soria, 184. 28043 Madrid. España.

E-mail: coma@vitanet.nu

Received October 1, 2007.

Accepted for publication October 1, 2007.