Acute myocarditis is an inflammatory process of the myocardium that most frequently affects children and young adults. Its forms of presentation include heart failure, arrhythmia, syncope, and sudden death.1 One of the most commonly involved viruses is Parvovirus B19,2 which has a special tropism for endothelial cells and has been associated with episodes of chest pain and isolated diastolic dysfunction.2–4Noninfectious causes include giant cell myocarditis and eosinophilic myocarditis. The definitive diagnosis is histological, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is very useful as a noninvasive diagnostic method.5

We report 3 patients with precordial pain, electrocardiographic changes and elevation of markers of myocardial damage. The differential diagnosis included acute myocarditis and myocardial ischemia. The analytic study ruled out other causes of chest pain, such as familial hypercholesterolemia. The diagnosis was made with MRI.

The first patient was a 10-year-old girl diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia with reactive eosinophilia. Her blood tests showed leucocytosis with eosinophilia. During the course of the disease, she showed a reduction in level of consciousness, and brain MRI showed lesions compatible with vascular disease. A few days later, she experienced precordial pain, electrocardiographic changes with ST depression in LI, LII, V1-V4 and T-wave inversion in all leads, and an increase in cardiac enzyme levels (maximum values: troponin T, 6.7 μg/L; creatine kinase-MB fraction, 38 μg/L). An echocardiogram showed normal coronary artery anatomy and increased left ventricular thickness (septum 10 mm [Z-score=2.56] and posterior wall 10 mm [Z-score=2.26]) with normal systolic function. The MRI scan showed inflammatory infiltrates in the free wall of the left ventricle and the interventricular septum. The clinical picture was considered to be that of eosinophilic myocarditis. Both the neurological and the cardiac pictures resolved by treating her underlying disease.

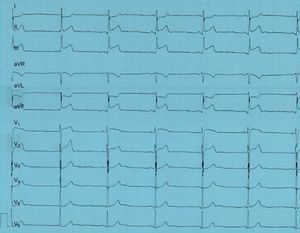

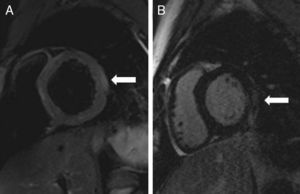

The second patient was a 14-year-old boy who presented to the emergency department was intense precordial pain, which was oppressive, unrelated to exercise and unaffected by postural changes. At admission, the patient had a fever of 38°C. The electrocardiogram showed ST elevation in the lower leads (LII, LIII and aVF) and V1 and V2 (Fig. 1). Troponin T was 2.8 μg/L and creatine kinase-MB fraction was 79 μg/L. The remaining blood test results were normal. An echocardiogram showed normal anatomy of the coronary arteries, a moderately dilated left ventricle (end-diastolic diameter: 61 mm [Z-score=2.48]), an ejection fraction of 45% and moderate mitral failure. An MRI scan showed an ejection fraction of 50% with a normal end-diastolic volume. A delayed enhancement study showed a pattern of patchy subepicardial enhancement in the lateral wall. An area of increased signal intensity was visible in the T2-weighted MRI image, which was suggestive of edema (Fig. 2).

The patient's course was favorable; his systolic function returned to normal with a decrease in markers of damage. The suspected diagnosis was acute myocarditis. At admission, the results of polymerase chain reaction of blood and nasopharyngeal aspirate were negative for viruses; therefore the causal agent was not identified.

The third patient was a 10-year-old girl who presented to the emergency department after experiencing 4 episodes of oppressive chest pain, radiating to her arm. Each episode lasted approximately 1 h. An echocardiogram showed moderate ST-elevation of 1 mm in LII, LIII and aVF, with troponin T at 9.12 μg/L and creatine kinase-MB fraction at 272 μg/L. An echocardiogram showed normal coronary artery anatomy, a hypertrophic left ventricle (septum 10 mm [Z-score=2.77]; posterior wall 9 mm [Z-score=2.13]), which was not dilated, with an ejection fraction of 65%. T2-weighted MRI scan showed subepicardial areas of increased signal intensity in the free wall of the left ventricle. The delayed enhancement sequences showed generalized, subepicardial enhancement of the left ventricle, compatible with acute myocarditis. Polymerase chain reaction testing of blood and nasopharyngeal aspirate was negative for viruses. The patient's course was favorable.

Precordial pain is a presentation of acute myocarditis and, although uncommon in children, should be included in the differential diagnosis.

The usefulness of MRI in these patients has been previously reported.6 The clinical course is usually favorable and the most commonly described causative agent is Parvovirus B19. In the cases reported here, the diagnostic utility of MRI should be emphasised as it allowed catheterization to be avoided in our patients. It should be performed as an emergency procedure and, if inconclusive, a coronary angiography should be conducted to rule out coronary disease.