Little is known about the usefulness of heart rate (HR) response to exercise for risk stratification in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Therefore, this study aimed to assess the association between HR response to exercise and the risk of total episodes of worsening heart failure (WHF) in symptomatic stable patients with HFpEF.

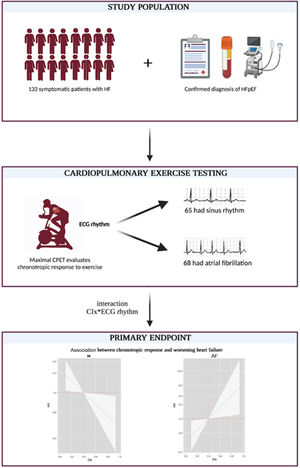

MethodsThis single-center study included 133 patients with HFpEF (NYHA II-III) who performed maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing. HR response to exercise was evaluated using the chronotropic index (CIx) formula. A negative binomial regression method was used.

ResultsThe mean age of the sample was 73.2± 10.5 years; 56.4% were female, and 51.1% were in atrial fibrillation. The median for CIx was 0.4 [0.3-0.55]. At a median follow-up of 2.4 [1.6-5.3] years, a total of 146 WHF events in 58 patients and 41 (30.8%) deaths were registered. In the whole sample, CIx was not associated with adverse outcomes (death, P=.319, and WHF events, P=.573). However, we found a differential effect across electrocardiographic rhythms for WHF events (P for interaction=.002). CIx was inversely and linearly associated with the risk of WHF events in patients with sinus rhythm and was positively and linearly associated with those with atrial fibrillation.

ConclusionsIn patients with HFpEF, CIx was differentially associated with the risk of total WHF events across rhythm status. Lower CIx emerged as a risk factor for predicting higher risk in patients with sinus rhythm. In contrast, higher CIx identified a higher risk in those with atrial fibrillation.

Keywords

Chronotropic incompetence (CI), defined as a diminished heart rate (HR) response to exercise, is associated with worse functional capacity and quality of life in heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).1,2 Likewise, increased resting HR has also been related to lower functional capacity and is a well-known precipitating factor for decompensations.3

Several studies have revealed that the presence of CI in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is associated with increased all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization.4–7 However, the evidence endorsing the role of chronotropic response is scarcer in HFpEF. Accordingly, we aimed to assess the association between chronotropic response in stable symptomatic patients with HFpEF and worsening heart failure (WHF) and whether this association is modified by the presence of atrial fibrillation (AF).

METHODSStudy designThis study prospectively included 133 consecutive outpatients with HFpEF and stable NYHA functional class II-III (figure 1). The study was conducted in a single third-level center in Spain. All patients provided informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the research ethics committee following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and national regulations.

Candidates were selected from the outpatient specialized HF unit. All patients met the following inclusion criteria: a) a previous history of symptomatic HF (New York Heart Association functional class ≥ II); b) normal left ventricular ejection fraction (ejection fraction> 0.50 by the Simpson method and end-diastolic diameter <60 mm); c) structural heart disease (left ventricular hypertrophy/left atrial enlargement) and/or diastolic dysfunction estimated by 2-dimensional echocardiography; and d) clinical stability, without hospital admissions in the past 3 months. Patients were excluded if they could not perform a valid baseline exercise test, had genetic or restrictive cardiomyopathies, had high suspicion of hypertrophic or amyloid cardiomyopathy, or showed any previous medical condition such as unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or cardiac surgery within the last 3 months; chronic metabolic, orthopedic, infectious disease, or pulmonary disease (including pulmonary arterial hypertension, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease, or moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease); acute HF decompensation; and any other comorbidity with a life expectancy of less than 1 year.

ProceduresPatients underwent maximal symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), echocardiography, physician-perceived NYHA class, clinical examination, and laboratory tests.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testingPatients were monitored with a 12-lead electrocardiogram and blood pressure measurements at baseline and every 2minutes during exercise. Patients were classified as those in sinus rhythm (SR) or AF at the moment of CPET.

Maximal functional capacity was evaluated using incremental and symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise testing on a bicycle ergometer, beginning with a workload of 10W and increasing gradually in a ramp protocol at 10W increments every 1minute. We define maximal functional capacity as when the patient stops pedalling because of symptoms and the respiratory exchange ratio (RER) was ≥ 1.05. Gas exchange data and cardiopulmonary variables are averages of values taken every 10seconds. Peak oxygen consumption (peak VO2) was the highest value 30-second average of oxygen consumption (VO2). Once peak VO2 was obtained, we calculated its percent of predicted peak VO2 (pp-peak VO2%), defined as the percentage of predicted peak VO2 adjusted for sex, age, exercise protocol, weight, and height according to the Wasserman/Hansen standard prediction equation.

Ventilatory efficiency was determined by measuring the slope of the linear relationship between minute ventilation (VE) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) across the entire course of exercise (VE/VCO2 slope) and was considered normal if the VE/VCO2 slope was <30.

HR response during maximal CPET was evaluated following the chronotropic index (CIx) formula=peak HR-rest HR/[(220-age)-restHR)].

EchocardiographyDoppler echocardiogram examinations were performed under resting conditions using 2-dimensional echocardiography. All parameters, including tissue Doppler parameters, were measured according to the European Society of Echocardiography.8

BiomarkersA blood sample was collected under standardized conditions for biomarker profiling. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), estimated glomerular filtration rate, electrolytes, and hemoglobin were measured on the same day as CPET.

EndpointsThe total number of WHF events was selected as the endpoint of interest. Additionally, all-cause mortality was also evaluated. WHF events inclunded hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and unplanned outpatient visits. The definition of WHF required worsening symptoms and signs of the disease and administration of parenteral diuretics. WHF events and survival status were identified from the clinical records of patients in the HF unit, hospital wards, emergency room, and electronic medical records. The endpoints were assessed by researchers blinded to the patients’ baseline characteristics, including CPET parameters. All patients included were follow-up until November 2021. The minimum duration of patient follow-up was 8.5 months.

Statistical analysisContinuous and categorical variables are presented as mean±standard deviation, median [interquartile range (IQR)], or percentages. Bivariate negative binomial regression was used to assess the independent association between CIx as a continuous variable and the prognostic endpoints (WHF events and all-cause mortality). For the clinical endpoints, bivariate negative binomial regression evaluated the interaction between CIx and electrocardiographic rhythm (SR vs AF). Estimates are reported as incidence rate ratios (IRR). All variables listed in table 1 were evaluated for prognostic purposes. The selection of the covariates in the final multivariate models was based on biological plausibility and not only on the P value. The linearity assumption for continuous variables was simultaneously tested and transformed, if appropriate, with fractional polynomials. In addition to our exposures (CIx and the interaction AF*CIx), the covariates included in the final models for WHF events were: baseline NYHA functional class, past smoker, estimated glomerular filtration rate, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction, left ventricular end-systolic volume, left ventricular end-diastolic volume, left ventricular mass index, left atrial volume, treatment with beta-blockers, and treatment with furosemide. A 2-sided a P value <.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata 15.1.

Baseline characteristics of the population stratified by rhythm status

| Total(n=133) | SR(n=65) | AF(n=68) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical variables | ||||

| Age, y | 73.2±10.5 | 73.7±8.6 | 72.7±12 | .577 |

| Women | 75 (56.4) | 37 (56.9) | 38 (55.9) | .904 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.1 [28-34.3] | 31.2 [28-34.2] | 31 [27.7-34.8] | .932 |

| NYHA III/IV | 45 (33.8) | 17 (26.2) | 28 (41.2) | .067 |

| Hypertension | 120 (90.2) | 59 (90.7) | 61 (89.7) | .836 |

| Past smoker | 41 (30.8) | 20 (30.8) | 21 (30.9) | .989 |

| Dyslipidemia | 102 (76.7) | 53 (81.5) | 49 (72.1) | .162 |

| IHD | 41 (30.8) | 28 (43.1) | 13 (19.1) | .003 |

| COPD | 13 (9.8) | 9 (13.9) | 4 (5.9) | .122 |

| Diabetes | 59 (44.4) | 29 (44.6) | 30 (44.1) | .954 |

| History of stroke | 9 (6.8) | 1 (1.5) | 8 (11.8) | .019 |

| Smoker | 6 (4.5) | 4 (6.1) | 2 (3.0) | .372 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||||

| LVEF | 66 [60-74] | 65.8 [59.7-74] | 67 [60-73] | .105 |

| TAPSE, mm | 22 [19.4-25] | 22 [20-25.4] | 21.6 [19-24] | .091 |

| PAPs, mmHg | 39.5 [30-49.5] | 36 [25-43] | 44 [34-53] | .001 |

| E/e’ ratio | 13 [10.2-16.3] | 12.3 [9.7-14.2] | 13.2 [10.5-18.4] | .036 |

| LVEDV, mL | 83 [65.8-108] | 83 [72-111] | 82.5 [63.5-102] | .317 |

| LVESV, mL | 29 [19.2-35.4] | 29 [21.7-35.4] | 29 [19-35] | .677 |

| Left atrial volume, mL | 80 [70-90.2] | 76 [61-80] | 80 [80-100] | <.001 |

| IVS thickness, mm | 12.5 [11.2-13.5] | 12.9 [12-13.5] | 12.5 [11-13.5] | .209 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 114.5 [96.8-143.9] | 113.7 [98-139.8] | 116 [96.7-146.9] | .223 |

| CPET parameters | ||||

| HR at rest, bpm | 67 [59-74] | 66 [60-73] | 68 [59-75] | .345 |

| HR at peak, bpm | 99 [85-112] | 96 [85-110] | 101 [86-112] | .565 |

| PeakVO2, mL/kg/min | 11 [9-13] | 10.3 [8.8-12] | 11.6 [9-13] | .109 |

| pp-peakVO2 | 64.1 [53-74.4] | 67.8 [54.8-79.7] | 61.7 [50-70.8] | .084 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 34.7 [31-38.9] | 34.7 [29.3-38.8] | 34.7 [31.7-39.3] | .477 |

| SBP at peak exercise, mmHg | 149 [140-160] | 152 [140-162] | 142 [138-150] | .001 |

| Chronotropic index | 0.4 [0.3-0.55] | 0.4 [0.26-0.55] | 0.4 [0.29-0.54] | .749 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 13.0 [11.7-14.1] | 13.2 [12.1-14.1] | 12.8 [11.6-13.8] | .362 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 556 [288-1399] | 325 [212-638] | 1095 [513- 2233] | <.001 |

| CA125, U/mL | 12 [8-19] | 10 [1-16] | 14 [10-23] | .001 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 141 [139-142] | 141 [139-143] | 141 [139-142] | .465 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 58.4 [43.6-74.2] | 60.6 [43.8-74.2] | 57.9 [43.5-74.7] | .007 |

| Medical treatment | ||||

| ARB | 66 (49.6) | 37 (56.9) | 29 (42.7) | .099 |

| ACEI | 26 (19.5) | 12 (18.5) | 14 (20.6) | .757 |

| MRA | 29 (21.8) | 7 (10.8) | 22 (32.4) | .002 |

| Beta-blockers | 118 (88.7) | 58 (89.2) | 60 (88.2) | .856 |

| Digoxin | 6 (4.5) | 3 (4.5) | 3 (4.5) | 1.000 |

| Furosemide | 73 (54.9) | 27 (41.5) | 46 (67.7) | .002 |

| Other diuretics | 52 (39.1) | 30 (46.2) | 22 (32.4) | .103 |

Data are expressed as No. (%), continuous variables as mean±1 standardard deviation, or medians (interquartile range [IQR]), and discrete variables as frequencies and percentages.

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CA125, antigen carbohydrate 125; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; E/e’, ratio between early mitral inflow velocity and mitral annular early diastolic velocity; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IHD, ischemic heart disease; IVS thickness, interventricular septum thickness; LV, left ventricular; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SR, sinus rhythm; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; VE/VCO2 slope, ventilatory efficiency.

The mean age of the sample was 73.2±10.5 years, 56.4% were female, 33.8% were in NYHA III, most of them showed prior history of hypertension, and 68 (51.1%) had AF. Most patients were previously admitted for acute HF (92%) and were on beta-blockers therapy (88.7%). Regarding CPET parameters, the median [p25-p75] for CIx, peak VO2, pp-peak VO2, and VE/VCO2 were 0.4 [0.3-0.55], 11 [9-13] mL/kg/min, 64.1 [53-74.4]%, and 34.7 [31-38.9], respectively.

Baseline characteristics were stratified by electrocardiographic rhythmTable 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics stratified by baseline electrocardiographic rhythm. Overall, patients with AF had a higher prevalence of stroke and data indicating more advanced disease (higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure, higher left atrial volume, lower systolic blood pressure at peak exercise, higher NT-proBNP levels, and lower estimated glomerular filtration rate), as shown in table 1. Likewise, patients with AF were more frequently treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and furosemide. However, there were no differences in baseline NYHA functional class, peak VO2, HR at rest, or CIx across the types of rhythm (SR vs AF).

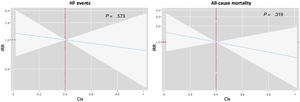

Chronotropic index and adverse clinical eventsAt a median [IQR] follow-up of 2.4 [1.6-5.3] years, a total of 41 (30.8%) all-cause deaths and 146 WHF events (62 hospitalizations and 84 ambulatory episodes) in 58 patients were registered. The rates (per 10-person-years) of death and WHF events did not differ across the median of CIx (< 0.4 vs ≥ 0.4): 1.03 vs 0.75 (P=.535) and 4.44 vs 3.58 (P=.544), respectively. On multivariable analysis, CIx was not associated with WHF events (P=.573) and all-cause mortality (P=.319), as depicted in figure 2. In the same multivariate scenario, when dichotomized in the median (< 0.4 vs ≥ 0.4), CIx remained not independenlty associated with WHF events (IRR, 0.55; 95%CI, 0.23-1.32; P=.182) or death (IRR, 0.87; 95%CI, 0.50-1.56; P=.657).

Differential prognostic effect of chronotropic index across the electrocardiographic rhythmPatients with CIx below the median (< 0.4) showed nonsignificant differences in mortality rates in SR (0.98 vs 0.45, P=.128) or AF (1.13 vs 1.28, P=.569). However, CIx <0.4 identified higher rates of WHF events in those patients with SR (4.93 vs 1.34, P=.003). In contrast, in patients with AF, CIx <0.4 showed a statistical trend to have lower rates of WHF events (2.66 vs 7.35, P=.068).

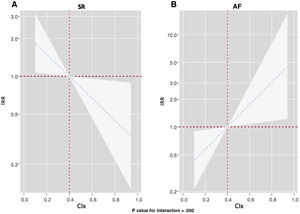

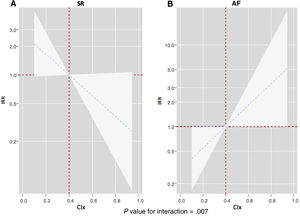

After multivariate adjustment, we confirmed a differential prognostic effect of CIx across electrocardiographic rhythms for predicting WHF events (P for interaction=.002). As depicted in figure 3, CIx was inversely and linearly associated with the risk of WHF events in patients in sinus rhythm (figure 3A). However, CIx was positively and linearly related to the risk of WHF events in those with AF (figure 3B). Similar results were found when we analyzed the differential prognostic effect of CIx only for HF hospitalizations (P for interaction=.007). Lower CIx was associated with a higher risk in those in SR (figure 4A), but we found the opposite in patients with AF (figure 4B).

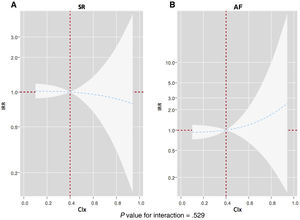

For all-cause mortality, the adjusted interaction between CIx and electrocardiographic rhythm was not significant (P for interaction=.529). CIx along the continuum was not associated with the risk of death in SR and AF (figure 5).

DISCUSSIONIn ambulatory symptomatic and stable HFpEF patients, we found that exercise chronotropic response evaluated by CIx was differentially associated with the risk of WHF events across electrocardiographic rhythms. In a multivariate regression model including CIx as a continuous variable, blunted HR response was associated with a higher risk of total WHF events at long-term follow-up in patients with SR. In contrast, a higher HR response increased the risk of WHF events in patients with AF. However, CIx was not associated with all-cause mortality.

Chronotropic response in heart failureAppropriate HR response to exercise is crucial for increasing cardiac output at maximal exercise in normal individuals9 and HF patients.10 CI is a common finding in patients with HF.1,6,11,12 In HFrEF, CI leads to exercise intolerance, impairs quality of life, and is associated with adverse events.4–6 Likewise, increased HR in HFrEF is also associated with adverse events13 and is a well-known therapeutic target.14

Regarding HFpEF, the optimal rest and exercise HR response remains elusive. Recent studies have revealed that blunted chronotropic response is a common finding associated with limited functional capacity.1,12 Despite the unclear pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CI in HFpEF, several potential mechanisms have been proposed for patients in SR: peripheral muscle dysfunction, autonomic nervous imbalance, sinus node remodeling causing a reduction in sinus node reserve, and impairment of cardiac beta-receptor responsiveness.7,11,15 Likewise, especially in patients with AF, the increased ventricular rate is a common precipitating factor for HF decompensations and a therapeutic target.14

Chronotropic response across rhythm status and prognosisIt is well-known that the development of AF in patients with HF is associated with a worse prognosis16 and poor functional capacity.10,17 However, in HFrEF, previous studies showed that HR response to exercise in HFrEF has different patterns in patients with SR and AF.10,17 For example, in a cohort of 942 patients with HFrEF, Agostoni et al.17 reported that those with AF exhibited lower values of peak VO2 and O2 pulse but higher HR values at peak exercise than participants in SR. This finding suggested that stroke volume may be lower at peak exercise and that higher HR response acted as a compensatory mechanism for increasing stroke volume in those patients with AF.17 Thus, an increased HR response could translate into an augmented sympathetic drive triggered to maintain cardiac output.10

In HFpEF, some studies have shown that patients with AF exhibited lower values of peak VO2 and O2 pulse but no differences in peak HR compared with those in SR.18,19 Elshazly et al., 19 evaluated the CPET differences across rhythm status in 1744 young HFpEF patients (239 patients—13.7%—in AF) with a mean age of 51.2±15.4 years. They found that AF patients had lower peak VO2, O2 pulse, and systolic blood pressure at peak exercise, a higher risk of long-term total mortality, and no differences in peak HR compared with those with SR.19 Likewise, the current study did not find differences in CIx across SR vs AF. However, the present findings suggest that the type of rhythm largely influences the association between chronotropic response to exercise and WHF events. Depending on rhythm status, an exaggerated chronotropic response might identify patients with HFpEF and a higher risk of WHF. Indeed, a rapid ventricular response is a common precipitating factor of HF decompensation in patients with AF.20

Conversely, a blunted response might select those with SR at higher risk in which CI might play a crucial causative role in determining the inability to increase cardiac output during exercise. Current findings are another example of the complex and heterogeneous pathophysiology of HFpEF. This case highlights the differential role of HF response during exercise across the type of electrocardiographic rhythm.

Clinical implications and future lines of researchUnder the premise that our findings need further validation in future trials, we propose that the withdrawal or reduction of HR-lowering treatment, or even HR increase, in patients with HFpEF with documented CI may be a therapeutic strategy to reduce the risk of WHF events and improve functional capacity, especially in those with SR. Along this line, a recent small randomized clinical that enrolled 52 patients with stable HFpEF (80.8% on SR), previous treatment with beta-blockers (stable for at least 3 months prior to inclusion), and documented CI (CI <0.62) showed that short-term peak VO2 and the percentage of predicted peak VO2 increased by +2.1±1.29mL/kg/min (P <.001) and + 11.74±2.32% (P <.001) after beta-blocker withdrawal. Interestingly, mediation analysis showed that the main contributor to the improvement in maximal functional capacity was the magnitude of changes in HR response.2 In contrast, a tight HR control using lowering HR treatments in those patients with AF and exaggerated exercise HR response may be a valuable strategy for preventing further episodes of WHF.20–23

Due to the large number of uncertainties in the diagnosis and management of HFpEF, future studies in this field should aim to provide: a) a better understanding of the pathophysiology of chronotropic response both in patients with SR and AF; b) more precise phenotyping of HFpEF regarding HR response, evaluating the optimal range of HR in patients with HFpEF and whether it is modified by AF or SR; and c) definition of the clinical utility of beta-blockers or other HR-lowering treatment according to HFpEF phenotype,24–26 type of electrocardiogram rhythm, and HR response.

Finally, this study emphasizes the role of exercise tests in evaluating patients with HFpEF. CPET is a useful clinical tool for identifying different exercise HR response phenotypes in HFpEF.

Study limitationsWe acknowledge that the main limitations of this study are the small sample size and the fact that this is an observational single-center study. Second, this is a selected population with high rates of beta-blocker prescription. Third, the current findings applied only to symptomatic patients with stable HFpEF. They cannot be extrapolated to other clinical scenarios, prevalent subgroups, or milder forms of the syndrome. Fourth, we did not register the longitudinal changes in the electrocardiographic type of rhythm or medical treatment during the follow-up. Finally, the low statistical power may explain some of the neutral findings.

CONCLUSIONSIn patients with clinically stable HFpEF, CIx was differentially associated with the risk of WHF events across rhythm status. In addition, CI emerged as a risk factor for predicting WHF events in patients with SR. Conversely, exaggerated HR response to exercise identified a subgroup at higher risk of WHF events in patients with HFpEF and AF. Further studies should confirm these results, elucidate the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms behind these findings, and define proper management.

FUNDINGThis work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness through the Carlos III Health Institute: FIS (PI17/01426), Unidad de Investigación Clínica y Ensayos Clínicos INCLIVA Health Research Institute, Spanish Clinical Research Network (SCReN; PT13/0002/0031 and PT17/0017/0003), cofunded by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional, Instituto de Salud Carlos III and CIBER Cardiovascular funds (16/11/00420 and 16/11/00403).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSP. Palau and E. Domínguez contributed equally. Study design and database creation: P. Palau, E. Domínguez and J. Núñez. Patient selection and inclusion of variables in the database: P. Palau, E. Domínguez, J. Núñez, J. Seller, C. Sastre, L. López, P. Llàcer, G. Miñana and R.l de la Espriella. Results assessment: P. Palau, J. Núñez, A. Bayés-Genís, J. Sanchis and V. Bodí. Critical review of the manuscript: P. Palau, E. Domínguez, J. Núñez, J. Seller, C. Sastre, L. López, P. Llàcer, G. Miñana, R. de la Espriella A. Bayés-Genís, J. Sanchis and V.T Bodí

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTJ. Sanchis is editor-in-chief of Rev Esp Cardiol. The journal's editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

- •

Chronotropic incompetence is associated with functional capacity and quality of life in heart failure with HFpEF.

- •

Previous evidence has shown that chronotropic incompetence in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is associated with increased all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization.

- •

However, little is known about the usefulness of heart rate response to exercise for risk stratification in heart failure with HFpEF.

- •

Heart rate response to exercise was differentially associated with the risk of HF events across rhythm status.

- •

Chronotropic incompetence increased the risk of heart failure events in patients in sinus rhythm.

- •

A higher heart rate response increased the risk of heart failure events in patients with atrial fibrillation.