Clinical practice guidelines recommend ticagrelor or prasugrel as first line drugs in non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI), and clopidogrel has been relegated to patients with contraindications to these drugs (especially high risk of bleeding).1 Elderly patients are under-represented in the clinical trials that support these recommendations. Possibly because of that, underuse of these drugs in everyday clinical practice has been described, especially in elderly patients with comorbidities.2–4 There is very little information on antiplatelet treatment and its impact on geriatric assessment in elderly patients with NSTEMI.

The LONGEVO-SCA registry included patients aged ≥ 80 years with NSTEMI from 44 Spanish hospitals, where the patients underwent an in-hospital geriatric assessment and their 6-month prognosis was analyzed.5 The primary endpoint of the study was total mortality and its causes at 6 months; secondary endpoints were the readmission, bleeding, and reinfarction rates and new revascularization procedures.

The aim of this analysis was to describe the clinical profile and outcomes in patients who survived to hospital admission, according to whether or not they were prescribed ticagrelor on discharge, excluding patients treated with oral anticoagulants (n = 86). The analysis included total mortality, readmissions, bleeding (BARC 2, 3, or 5) and ischemic events (cardiac mortality, reinfarction, or new revascularization procedures) at 6 months. Cox regression was used for the adjusted analysis, with the variables that showed an association (P < 0.1) with either exposure (ticagrelor) or effect: admitting unit, age, previous heart failure, atrial fibrillation, Killip class, hemoglobin, creatinine clearance, invasive management, left main trunk stenosis, revascularization during admission, GRACE, CRUSADE and PRECISE-DAPT scores, and Lawton-Brody, Charlson, nutritional risk, and frailty indexes.

The analysis included 413 patients, 63 of whom (15.2%) received ticagrelor on discharge. These patients were admitted more often to critical care units, were younger, and more often male (Table 1). They had a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation and bleeding prior to admission. Furthermore, they had slightly lower GRACE scores, with a lower bleeding risk profile. They underwent coronary angiography more often and had a higher percentage of left main trunk stenosis and a higher frequency of percutaneous revascularization.

Baseline Characteristics, Treatment and Prognosis According to Ticagrelor Prescription at Discharge

| Ticagrelor at discharge (n = 63) | No ticagrelor at discharge (n = 350) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admitting unit | .011 | ||

| Intensive care | 9 (14.3) | 20 (5.7) | |

| Coronary care unit | 17 (27) | 73 (20.9) | |

| Cardiology ward | 33 (52.4) | 221 (63.1) | |

| Internal medicine | 0 | 22 (6.3) | |

| Elderly care | 0 | 5 (1.4) | |

| Other | 4 (6.3) | 9 (2.6) | |

| Age. y | 82.7 ± 2.6 | 84.8 ± 4 | .001 |

| Male | 49 (77.8) | 206 (58.9) | .006 |

| Body mass index | 27.5 ± 4 | 26.6 ± 4 | .084 |

| Hypertension | 53 (84.1) | 297 (84.8) | .642 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 (42.9) | 133 (38) | .531 |

| Previous stroke | 6 (9.5) | 51 (14.3) | .515 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 6 (9.5) | 50 (14.3) | .288 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 18 (28.6) | 127 (36.3) | .203 |

| Previous heart failure | 4 (6.3) | 57 (16.3) | .037 |

| Previous atrial fibrillation | 1 (1.6) | 31 (8.9) | .027 |

| Previous bleeding | 1 (1.6) | 23 (6.6) | .089 |

| Previous neoplasm | 9 (14.3) | 58 (16.6) | .612 |

| Killip class ≥ II on admission | 12 (19.0) | 126 (28.9) | .078 |

| Baseline hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.1 ± 2 | 12.6 ± 2 | .081 |

| Creatinine clearance | 53 ± 20) | 48 ± 20 | .042 |

| LVEF, % | 56 ± 11 | 53 ± 12 | .191 |

| Invasive management | 59 (93.7) | 258 (73.7) | .001 |

| Left main trunk stenosis | 17 (28.8) | 38 (14.7) | .001 |

| Multivessel disease | 38 (64.4) | 137 (53.1) | .053 |

| Revascularization | .001 | ||

| No | 8 (12.7) | 177 (50.6) | |

| PCI | 54 (85.7) | 167 (47.7) | |

| Coronary surgery | 1 (1.6) | 6 (1.7) | |

| GRACE score | 159 ± 22 | 166 ± 29 | .090 |

| CRUSADE score | 36 ± 11 | 42 ± 13 | .001 |

| PRECISE-DAPT score | 32.9 ± 10 | 39 ± 12 | .001 |

| Geriatric syndromes | |||

| Disability (Barthel index) | .135 | ||

| Independent | 49 (77.8) | 217 (62) | |

| Mild dependency | 12 (19) | 94 (26.9) | |

| Moderate dependency | 1 (1.6) | 19 (5.4) | |

| Severe dependency | 1 (1.6) | 11 (3.1) | |

| Completely dependent | 0 | 9 (2.6) | |

| Instrumental activities (Lawton-Brody index) | 6.3 ± 2 | 5.3 ± 3 | .001 |

| Comorbidity (Charlson index) | 2 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 1.9 | .040 |

| Cognitive impairment (Pfeiffer test) | .149 | ||

| None | 49 (77.8) | 227 (64.9) | |

| Moderate | 13 (20.6) | 112 (32) | |

| Severe | 1 (1.6) | 9 (2.6) | |

| Nutritional risk (MNA-SF) | 24 (38.7) | 189 (54) | .020 |

| Frailty (FRAIL scale) | .007 | ||

| No | 29 (46) | 110 (31.4) | |

| Pre-frail | 27 (42.9) | 140 (40) | |

| Frail | 7 (11.1) | 100 (22.6) | |

| Events at 6 months | |||

| Bleeding | 2 (3.2) | 19 (5.4) | .420 |

| Readmission due to bleeding | 0 | 14 (4) | .087 |

| Required transfusion | 0 | 9 (2.5) | .211 |

| Intervention due to bleeding | 1 (1.6) | 3 (0.9) | .496 |

| Change in antiplatelet agent | 1 (1.6) | 13 (3.7) | .326 |

| Fatal bleeding | 0 | 1 (0.3) | .843 |

| Cardiac death, reinfarction, or new revascularization | 5 (7.9) | 61 (17.4) | .057 |

| Cardiac death | 2 (3.2) | 26 (7.4) | .168 |

| Reinfarction | 4 (6.3) | 37 (10.6) | .299 |

| New revascularization | 1 (1.6) | 20 (5.7) | .138 |

| Total mortality | 2 (3.2) | 44 (12.6) | .029 |

| Readmission | 10 (15.9) | 131 (30) | .018 |

| Death or readmission | 11 (17.5) | 127 (36.3) | .004 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MNA-SF, Mini nutritional asssessment-Short Form; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

The patients in the ticagrelor group had a greater capacity for instrumental activities, lower degrees of comorbidity, and a lower prevalence of frailty and nutritional risk.

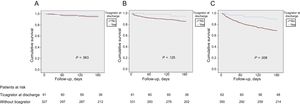

The incidence of bleeding was low in both groups, with no significant differences (3.2% vs 5.4%). The patients in the ticagrelor group had a slightly lower incidence of ischemic events and a lower incidence of death or readmission (Figure 1). After adjustment for confounding factors, the effect of treatment with ticagrelor was clearly not significant for either ischemic events (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.81; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.33-4.21; P = .807) or mortality or readmission (HR = 0.79; 95%CI, 0.37-1.73; P = .565).

The findings of this study are in line with those of previous publications and show the low rate of ticagrelor use in elderly patients in our setting,2 which is inversely proportional to the ischemic and bleeding risk.3,4

Some factors limit the robustness of these findings. This was an observational registry, with probable selection bias and unmeasured confounding factors. The small size of the ticagrelor group made it difficult to study the impact of treatment on outcomes. Finally, a longer follow-up would have allowed us to optimize the study of mid-term outcomes, although it is known that the highest risk of bleeding is concentrated in the first months after an event.

Nonetheless, in light of these results, it seems justified to assert that, although the adjusted analysis did not show a clinical benefit, ticagrelor is reasonably safe for selected patients ≥ 80 years, despite their theoretical bleeding risk profile (more than 85% of the ticagrelor group had a PRECISE-DAPT score ≥ 25, considered high bleeding risk in the recent guidelines1). This patient profile has scarcely been studied yet continues to grow in our everyday clinical practice.

FUNDINGThe LONGEVO-SCA registry has received funding from the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTA. Ariza-Solé has received conference fees from AstraZeneca.

.

The LONGEVO-SCA registry investigators.