Transfemoral aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in patients with a mechanical mitral prosthesis is a challenging procedure, due to the potential for prosthesis underexpansion, the risk of embolization, and interference due to the mitral prosthesis poppets.

Balloon predilation of the stenotic valve has been considered an essential step for valve preparation in TAVI procedures. However, recent publications have shown the safety and efficacy of direct implantation without previous valvuloplasty, which would simplify the procedure and could help ensure greater prosthetic stability during deployment and a lower incidence of cerebral embolic complications.1,2

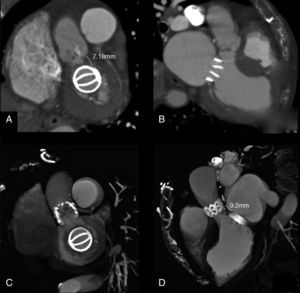

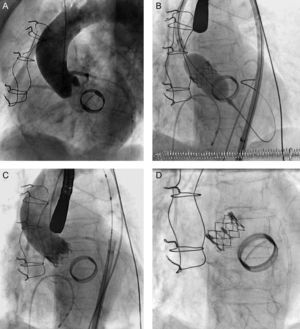

We describe the clinical case of an 81-year-old patient with severe aortic stenosis and an Edwards-Mira 27 mechanical mitral prosthesis who underwent direct TAVI with an Edwards-SAPIEN XT valve at our hospital, following admission to our hospital for dyspnea. On admission, transesophageal echocardiography showed a moderately calcified tricuspid aortic valve, with symmetric opening and valvular area of 0.7 cm2. A computed tomography scan showed an iliofemoral axis of good diameter, with a distance >7 mm between the aortic annulus and the mitral valve (Figs. 1A and B). Coronary angiography revealed severe disease in the anterior descending artery, treated with two overlapping stents; aortography ruled out significant aortic regurgitation (Fig. 2A, video 1).

A decision was made to implant a 23-mm Edwards-SAPIEN XT valve with no previous valvuloplasty. Good valve expansion was confirmed by fluoroscopy guidance (Fig. 2B, video 2) and transesophageal echocardiography, and no perivalvular regurgitation (Fig. 2C, video 3) or prosthetic mitral valve interference (Fig. 2D) was observed after implantation. A predischarge computed tomography scan confirmed that both prostheses were in the correct position (Figs. 1C and D).

The presence of a mitral prosthesis was originally considered a formal contraindication for transcatheter aortic valve implantation, and these patients were excluded from the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER valves) study. It was considered that the mitral annulus rigidity and the tighter space in the mitral-aortic plane could prevent adequate valve deployment, favor embolization, and increase the risk of underexpansion and malfunction due to mitral valve poppets interference. Rodés-Cabau et al.3 were the first to report transapical implant of an Edwards-SAPIEN valve in the presence of a mechanical mitral prosthesis. Several cases have since been published; most were transapical, as it was considered that this approach provided greater stability in valve deployment.4 Early cases of TAVI in patients with a mitral prosthesis were performed using a CoreValve prosthesis, and it was confirmed that there was no deformation of the nitinol tubing of the valve or interference due to the poppets of the mitral prosthesis.5 García et al.6 published the first 3 cases of TAVI with an Edwards-SAPIEN XT valve, in 3 women with ATS 29 and St. Jude mechanical mitral prostheses. The authors recommended a thorough study of patients before the procedure, with particular emphasis on the characteristics and profile of the mitral valve prosthesis, as they considered that there should be sufficient distance between the lower edge of the annulus and the upper edge of the mitral valve prosthesis. This distance was not specified, although it was considered advisable that the distance be at least 3mm in transapical implants and 7mm in transfemoral implants.6

Furthermore, it appears that direct TAVI without prior valvuloplasty offers several advantages, such as a lower risk of stroke, greater stability in valve deployment, and lower perivalvular aortic regurgitation; however, no randomized studies have compared the 2 techniques.1,2 To our knowledge, this is the first published case of direct TAVI in the presence of mechanical mitral prosthesis.

To ensure success in this type of procedure, patients should be carefully selected and direct implantation considered if the valve opens correctly and symmetrically, with no significant calcification of the leaflets or excessive commissural fusion. In addition, rapid valve placement at the annulus is recommended to shorten flow obstruction time and to obtain greater hemodynamic stability; inflation should be started slowly such that any undesirable movement of the prosthesis can be corrected, if necessary.

This case shows that a TAVI implant without predilation in the presence of a mitral mechanical prosthesis is feasible and safe and can offer advantages over the conventional method. Future studies are needed to compare the 2 implant techniques with the various models of percutaneous valve prostheses.