Current guidelines do not recommend routine thrombus aspiration in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) because no benefits were observed in previous randomized trials. However, there are limited data in cardiogenic shock (CS) complicating AMI.

MethodsWe included 575 patients with AMI complicated by CS. The participants were stratified into the TA and no-TA groups based on use of TA. The primary outcome was a composite of 6-month all-cause death or heart failure rehospitalization. The efficacy of TA was additionally assessed based on thrombus burden (grade I-IV vs V).

ResultsNo significant difference was found in in-hospital death (28.9% vs 33.5%; P=.28), or 6-month death, or heart failure rehospitalization (32.4% vs 39.4%; HRadj: 0.80; 95%CI, 0.59-1.09; P=.16) between the TA and no-TA groups. However, in 368 patients with a higher thrombus burden (grade V), the TA group had a significantly lower risk of 6-month all-cause death or heart failure rehospitalization than the no-TA group (33.4% vs 46.3%; HRadj: 0.59; 95%CI, 0.41-0.85; P=.004), with significant interaction between thrombus burden and use of TA for primary outcome (adjusted Pint=.03).

ConclusionsRoutine use of TA did not reduce short- and mid-term adverse clinical outcomes in patients with AMI complicated by CS. However, in select patients with a high thrombus burden, the use of TA might be associated with improved clinical outcomes. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02985008).

Keywords

Thrombus aspiration (TA) in a coronary artery has been adopted in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as an adjunctive nonpharmacological strategy designed to evacuate thrombotic material from the culprit coronary artery.1 TA was theoretically considered to reduce distal embolization, improve microvascular perfusion, and further produce positive outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI).2 Previously, this concept was supported in several studies by reports of improved myocardial perfusion3,4 and a lower incidence of death and major adverse cardiac events.5–7 However, these results were challenged in large-scale randomized trials that did not show previously identified benefits of TA and showed routine TA to be associated with an increased risk of stroke.8,9 Therefore, guidelines do not recommend routine TA in ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI).10,11 Despite these recommendations, TA may prove beneficial in selected patients, such as those with high thrombus burden.2

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is a life-threatening condition with high morbidity and mortality, and AMI remains the most frequent cause of CS.12 Because patients with AMI complicated by CS are more likely to have a high thrombus burden than participants without hemodynamic instability, TA might benefit selected patients with AMI complicated by CS.13 Data are insufficient to conclusively prove the effects of TA in AMI complicated by CS; only 2 studies have been conducted on the effects of TA in AMI patients with CS, and the results were conflicting.14,15 Furthermore, the results of previous randomized studies do not reflect the outcomes of CS patients because they generally excluded this population or only included a small number of participants. Therefore, we investigated whether TA may improve clinical outcomes in patients with AMI complicated by CS using a dedicated CS registry.

METHODSStudy population and data collectionThe Retrospective and prospective observational study to investigate clinical outcomes and efficacy of left ventricular assist device for Korean patients with cardiogenic shock (RESCUE; NCT02985008 at www.clinicaltrials.gov) study is a nationwide, prospective, and retrospective, multicenter registry investigating clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of CS in Korea. The design of the registry has been previously described.16 From January 2014 to December 2018, 12 tertiary hospitals participated in this study and enrolled consecutive patients with CS. Inclusion criteria were systolic blood pressure <90mmHg for 30minutes or need for inotrope or vasopressor support to achieve a systolic blood pressure> 90mmHg and presence of pulmonary congestion and signs of impaired organ perfusion (altered mental status, cold periphery, oliguria <0.5mL/kg/h for the previous 6hours, or blood lactate> 2 mmol/L). Exclusion criteria were out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and evidence of other causes of shock.

Patients with AMI complicated by CS were selected for this study. AMI was defined according to the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.17 We excluded patients whose culprit lesion was nonthrombotic and those with failed PCI and who underwent coronary bypass surgery or medical therapy (eg, for vasospasm) instead. We also excluded patients whose coronary angiograms were not available for review. Finally, 575 patients were enrolled and classified into the TA group if TA was performed during PCI, regardless of timing, or the no-TA group if TA was not performed during PCI ().

Baseline demographic, angiographic, procedural data, and adverse outcomes during the follow-up period were collected from the registry by research coordinators via web-based case report forms. All baseline data were measured upon patient admission. Additional information was obtained from medical records if necessary. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating centers and the requirement for informed consent was waived in retrospectively enrolled patients. Informed consent was obtained before enrollment from all prospectively enrolled patients. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

PCI procedures and angiographic core laboratory analysisAll coronary revascularization and related medical therapy was performed according to standard guidelines.18 A loading dose of aspirin (300mg) and P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel 300-600mg, ticagrelor 180mg, or prasugrel 60mg) before PCI was administered unless the patient was regularly taking these medications. Anticoagulation during PCI was performed using unfractionated heparin to achieve an activated clotting time of 250-300seconds. Invasive coronary angiography was performed via a transradial or transfemoral approach based on standard techniques. Diagnostic angiograms were obtained, and PCI was performed using current standard techniques with second-generation drug-eluting stents or drug-eluting balloons. During PCI, the type of stent or balloon, stenting technique, use of adjunctive drug therapy (eg, glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitor) or TA, additional imaging devices (eg, intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography), and poststent adjunctive balloon inflation were left to the operator's discretion.

All angiograms were collected and analyzed at a core laboratory. The thrombotic nature of the coronary lesions was first determined, and their respective location, thrombus burden as graded based on the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) thrombus burden classification system,19 and TIMI flow grades were recorded. The grading was performed by 2 cardiologists in a blinded fashion. The SYNTAX score was calculated to assess the atherosclerotic burden in epicardial coronary arteries using an online SYNTAX score calculator. The residual SYNTAX score was based on the last frames of final angiography during the index hospitalization to analyze the residual ischemic burden after PCI.

Definitions and outcomesPrimary outcome was a composite of all-cause death or rehospitalization due to heart failure at 6 months. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital death and other 6-month cardiovascular outcomes including all-cause death, cardiac death, rehospitalization due to heart failure, MI, and stroke. All deaths were considered cardiac related unless a definite noncardiac cause was established. MI was defined as elevated cardiac enzymes (troponin or myocardial band fraction of creatine kinase) greater than the upper reference limit with concomitant ischemic symptoms or electrocardiography findings indicative of ischemia. Periprocedural MI was not included as a clinical event. Stroke was defined as neurological deficit attributable to an acute focal injury of the central nervous system caused by cerebral infarction or hemorrhage.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are presented as numbers and relative frequencies (%) and were compared using the chi-square test. Continuous variables are presented as means±standard deviations, or median [interquartile range] if they did not follow normal distribution and were analyzed using Welch t-tests. The cumulative incidence of primary and secondary endpoints at 6 months was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the significance level was compared between TA and no-TA groups using the log-rank test. Landmark analysis was also done with 30-day reference point to observe different pattern of clinical course according to time. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), and the proportional hazards assumptions of the HRs in the Cox proportional hazards models were graphically inspected in the log minus log plot and tested using Schoenfeld residuals. Multivariable models for Cox regression included use of TA, age older than 70 years, diabetes mellitus, type of AMI at presentation, left ventricular ejection fraction less than 30%, the presence of multivessel disease, baseline creatinine value, use of a mechanical support system, and pre- and post-PCI SYNTAX score tertiles as variables. Propensity score matching and inverse probability weighted (IPW)-adjusted analysis were done with the factors presented in to provide a different method of adjusting for baseline differences, after which Cox proportional hazards were calculated using a univariate model.

All probability values were 2 -sided, and P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria).

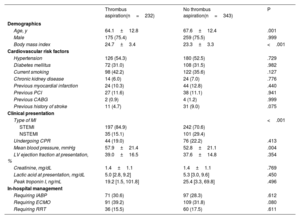

RESULTSBaseline characteristicsIn the present study, TA was performed in 232 patients (40.3%). Comparisons of baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics between the TA and no-TA groups are shown in table 1 and table 2, respectively. Participants who received TA were significantly older, more likely to present with STEMI, and had a higher peak troponin I value than patients with AMI complicated by CS who did not undergo TA. Other cardiovascular risk factor profiles and in-hospital management of CS did not significantly differ between the 2 groups. Regarding angiographic characteristics, the TA group had a significantly lower proportion of multivessel disease and lower SYNTAX scores before and after the procedure (table 2). However, high thrombus burden (grade V) was more often observed in the TA group than in the no-TA group. In addition, glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors were more frequently administered, and a higher amount of contrast was used in the TA group. Final TIMI flow and the proportion of no-reflow during the procedure did not significantly differ between the 2 groups.

Baseline clinical characteristics and in-hospital management

| Thrombus aspiration(n=232) | No thrombus aspiration(n=343) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 64.1±12.8 | 67.6±12.4 | .001 |

| Male | 175 (75.4) | 259 (75.5) | .999 |

| Body mass index | 24.7±3.4 | 23.3±3.3 | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 126 (54.3) | 180 (52.5) | .729 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 72 (31.0) | 108 (31.5) | .982 |

| Current smoking | 98 (42.2) | 122 (35.6) | .127 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14 (6.0) | 24 (7.0) | .776 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 24 (10.3) | 44 (12.8) | .440 |

| Previous PCI | 27 (11.6) | 38 (11.1) | .941 |

| Previous CABG | 2 (0.9) | 4 (1.2) | .999 |

| Previous history of stroke | 11 (4.7) | 31 (9.0) | .075 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Type of MI | <.001 | ||

| STEMI | 197 (84.9) | 242 (70.6) | |

| NSTEMI | 35 (15.1) | 101 (29.4) | |

| Undergoing CPR | 44 (19.0) | 76 (22.2) | .413 |

| Mean blood pressure, mmHg | 57.9±21.4 | 52.8±21.1 | .004 |

| LV ejection fraction at presentation, % | 39.0±16.5 | 37.6±14.8 | .354 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.4±1.1 | 1.4±1.1 | .769 |

| Lactic acid at presentation, mg/dL | 5.0 [2.8, 9.2] | 5.3 [3.0, 9.6] | .450 |

| Peak troponin I, ng/mL | 19.2 [1.5, 101.8] | 25.4 [3.3, 69.8] | .496 |

| In-hospital management | |||

| Requiring IABP | 71 (30.6) | 97 (28.3) | .612 |

| Requiring ECMO | 91 (39.2) | 109 (31.8) | .080 |

| Requiring RRT | 36 (15.5) | 60 (17.5) | .611 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenator; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEMI, non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RRT, renal replacement therapy; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Values are expressed as No. (%), median [first interquartile, third interquartile], or mean±standard deviation.

Baseline angiographic and procedural characteristics

| Thrombus aspiration(n=232) | No thrombus aspiration(n=343) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiographic characteristics | |||

| Multivessel disease | 157 (67.7) | 277 (80.8) | .001 |

| Number of involved vessels | <.001 | ||

| 1-vessel | 75 (32.3) | 66 (19.2) | |

| 2-vessels | 104 (44.8) | 149 (43.4) | |

| 3-vessels | 53 (22.8) | 128 (37.3) | |

| Infarct-related artery | .397 | ||

| Left anterior descending | 88 (37.9) | 150 (43.7) | |

| Left circumflex | 22 (9.5) | 36 (10.5) | |

| Right coronary | 94 (40.5) | 116 (33.8) | |

| Left main | 28 (12.1) | 41 (12.0) | |

| Thrombus site | .532 | ||

| Left anterior descending | 92 (39.7) | 149 (43.4) | |

| Left circumflex | 19 (8.2) | 34 (9.9) | |

| Right coronary | 94 (40.5) | 119 (34.7) | |

| Left main | 27 (11.6) | 41 (12.0) | |

| Thrombus grade | <.001 | ||

| I | 2 (0.9) | 6 (1.7) | |

| II | 1 (0.4) | 7 (2.0) | |

| III | 10 (4.3) | 40 (11.7) | |

| IV | 42 (18.1) | 99 (28.9) | |

| V | 177 (76.3) | 191 (55.7) | |

| Preprocedural TIMI flow | <.001 | ||

| 0 | 177 (76.3) | 191 (55.7) | |

| 1 | 27 (11.6) | 28 (8.1) | |

| 2 | 10 (4.3) | 48 (14.0) | |

| 3 | 18 (7.8) | 76 (22.2) | |

| Preprocedural SYNTAX score | 20.8 [13.0, 28.5] | 22.5 [15.0, 31.0] | .012 |

| Classification by tertiles | .102 | ||

| Low (< 16) | 89 (38.4) | 105 (30.6) | |

| Intermediate (16-22) | 48 (20.7) | 69 (20.1) | |

| High (> 22) | 95 (40.9) | 169 (49.3) | |

| Postprocedural SYNTAX score | 2.0 [0.0, 7.0] | 4.0 [0.0, 11.0] | <.001 |

| Classification by tertiles | .001 | ||

| Low (< 16) | 218 (94.0) | 289 (84.3) | |

| Intermediate (16-22) | 8 (3.4) | 23 (6.7) | |

| High (> 22) | 6 (2.6) | 31 (9.0) | |

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| Transradial approach | 39 (16.8) | 62 (18.1) | .780 |

| Amount of contrast used, mL | 180.0 [127.5, 231.5] | 150.0 [105.0, 200.0] | .036 |

| Use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 93 (40.1) | 41 (12.0) | <.001 |

| Final TIMI flow | .127 | ||

| 0-2 | 49 (21.1) | 53 (15.4) | |

| 3 | 183 (78.9) | 290 (84.5) | |

| No-reflow | 18 (7.8) | 20 (5.8) | .458 |

SYNTAX, Synergy Between PCI With Taxus and Cardiac Surgery; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Values are expressed as No. (%), median [first interquartile, third interquartile], or mean±standard deviation.

In the study population, 368 patients (64%) had high thrombus burden (grade V). Comparison of baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics between patients with grade V thrombus and nongrade V thrombus are presented in . Use of TA was significantly more frequent in the grade V group. Among patients with grade V thrombus, comparison of baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics according to use of TA are shown in .

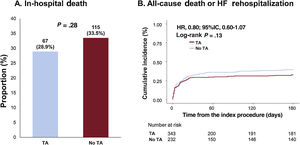

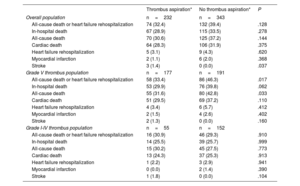

Clinical outcomesOverall, in-hospital death (TA vs no-TA; 28.9% vs 33.5%; P=.28) did not significantly differ between the TA and no-TA groups (figure 1A and table 3). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the 6-month risk of all-cause death or rehospitalization (32.4% vs 39.4%, adjusted HR (HRadj): 0.80; 95%CI, 0.59-1.09; P=.16), all-cause death (30.6% vs 37.2%; HRadj: 0.81; 95%CI, 0.59-1.11; P=.20), cardiac death (28.3% vs 31.9%; HRadj: 0.89; 95%CI, 0.64-1.25; P=.51), and rehospitalization due to heart failure (3.1% vs 4.3%; HRadj: 0.62; 95%CI, 0.19-2.01; P=.42) between the 2 groups (figure 1B, table 3, and table 4). However, the TA group showed a significantly higher risk of stroke than the no-TA group (1.4% vs 0%; P=.04; table 3).

Comparison of in-hospital death and 6-month death or rehospitalization due to heart failure between the thrombus aspiration and no thrombus aspiration groups. Analysis of the study population showed no significant differences between the thrombus aspiration group and no thrombus aspiration groups in in-hospital death and 6-month death or rehospitalization due to heart failure. TA, thrombus aspiration.

Comparison of in-hospital and 6-month clinical outcomes based on thrombus aspiration

| Thrombus aspiration* | No thrombus aspiration* | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall population | n=232 | n=343 | |

| All-cause death or heart failure rehospitalization | 74 (32.4) | 132 (39.4) | .128 |

| In-hospital death | 67 (28.9) | 115 (33.5) | .278 |

| All-cause death | 70 (30.6) | 125 (37.2) | .144 |

| Cardiac death | 64 (28.3) | 106 (31.9) | .375 |

| Heart failure rehospitalization | 5 (3.1) | 9 (4.3) | .620 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (1.1) | 6 (2.0) | .368 |

| Stroke | 3 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | .037 |

| Grade V thrombus population | n=177 | n=191 | |

| All-cause death or heart failure rehospitalization | 58 (33.4) | 86 (46.3) | .017 |

| In-hospital death | 53 (29.9) | 76 (39.8) | .062 |

| All-cause death | 55 (31.6) | 80 (42.8) | .033 |

| Cardiac death | 51 (29.5) | 69 (37.2) | .110 |

| Heart failure rehospitalization | 4 (3.4) | 6 (5.7) | .412 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (1.5) | 4 (2.6) | .402 |

| Stroke | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | .160 |

| Grade I-IV thrombus population | n=55 | n=152 | |

| All-cause death or heart failure rehospitalization | 16 (30.9) | 46 (29.3) | .910 |

| In-hospital death | 14 (25.5) | 39 (25.7) | .999 |

| All-cause death | 15 (30.2) | 45 (27.5) | .773 |

| Cardiac death | 13 (24.3) | 37 (25.3) | .913 |

| Heart failure rehospitalization | 1 (2.2) | 3 (2.9) | .941 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | .390 |

| Stroke | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | .104 |

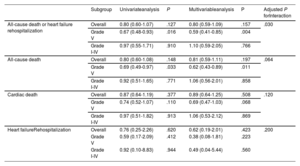

Subgroup analysis of 6-month clinical outcomes based on thrombus burden

| Subgroup | Univariateanalysis | P | Multivariableanalysis | P | Adjusted P forInteraction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause death or heart failure rehospitalization | Overall | 0.80 (0.60-1.07) | .127 | 0.80 (0.59-1.09) | .157 | .030 |

| Grade V | 0.67 (0.48-0.93) | .016 | 0.59 (0.41-0.85) | .004 | ||

| Grade I-IV | 0.97 (0.55-1.71) | .910 | 1.10 (0.59-2.05) | .766 | ||

| All-cause death | Overall | 0.80 (0.60-1.08) | .148 | 0.81 (0.59-1.11) | .197 | .064 |

| Grade V | 0.69 (0.49-0.97) | .033 | 0.62 (0.43-0.89) | .011 | ||

| Grade I-IV | 0.92 (0.51-1.65) | .771 | 1.06 (0.56-2.01) | .858 | ||

| Cardiac death | Overall | 0.87 (0.64-1.19) | .377 | 0.89 (0.64-1.25) | .508 | .120 |

| Grade V | 0.74 (0.52-1.07) | .110 | 0.69 (0.47-1.03) | .068 | ||

| Grade I-IV | 0.97 (0.51-1.82) | .913 | 1.06 (0.53-2.12) | .869 | ||

| Heart failureRehospitalization | Overall | 0.76 (0.25-2.26) | .620 | 0.62 (0.19-2.01) | .423 | .200 |

| Grade V | 0.59 (0.17-2.09) | .412 | 0.38 (0.08-1.81) | .223 | ||

| Grade I-IV | 0.92 (0.10-8.83) | .944 | 0.49 (0.04-5.44) | .560 |

The no thrombus aspiration group was used as reference. Variables used in multivariable analysis included use of thrombus aspiration, age over 70, diabetes mellitus, left ventricular ejection fraction <30%, type of myocardial infarction, presence of multivessel disease, baseline creatinine value, use of mechanical support system, pre- and post-PCI SYNTAX score tertiles.

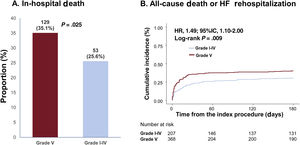

Patients with high thrombus burden (grade V) were associated with a significantly higher risk of in-hospital death (grade I-IV vs V; 25.6% vs 35.1%; P=.025) compared with participants with low thrombus burden (grades I-IV; figure 2A). The cumulative incidence of all-cause death or rehospitalization due to heart failure at 6 months was also significantly higher in the grade V thrombus burden group than in the grade I-IV thrombus burden group (30.5% vs 40.1%; HR: 1.49; 95% CI, 1.10-2.00; P=.009; figure 2B).

Comparison of in-hospital death and 6-month death or rehospitalization due to heart failure based on thrombus burden. Grade V thrombus was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality and 6-month mortality or rehospitalization due to heart failure compared with grade I-IV thrombus in cardiogenic shock patients. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CS, cardiogenic shock; HF, heart failure.

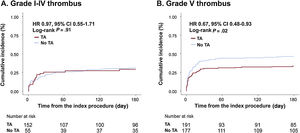

To assess the differential effects of TA on clinical outcomes based on initial thrombus grade for patients with AMI complicated by CS, data were analyzed for participants who presented with high (grade V) or low thrombus burden (grade I-IV). Notably, among patients with high thrombus burden, all-cause death or rehospitalization due to heart failure at 6 months was less frequently observed in the TA group than in the no-TA group (TA vs no-TA; 33.4% vs 46.3%; HRadj: 0.59; 95%CI, 0.41-0.85; P=.004; figure 3A, table 3, and table 4). Conversely, among patients with low thrombus burden, no significant difference was observed in the primary outcome between the 2 groups (TA vs no-TA; 30.9% vs 29.3%; HRadj: 1.10; 95%CI, 0.59-2.05; P=.77; figure 3B, table 3, and table 4). Landmark analysis with 30-day reference point showed that the difference was significant before the 30-day point and then became nonsignificant in the patients with high thrombus burden. In those with low thrombus burden, the difference between the TA and the no-TA group was nonsignificant both before and after the 30-day point (). Significant interaction (adjusted P for interaction=.03) was observed between thrombus burden and use of TA for a composite of all-cause death or heart failure rehospitalization at 6 months.

Comparison of 6-month mortality or heart failure rehospitalization between the thrombus aspiration and no thrombus aspiration groups in participants with grade I-IV thrombus and grade V thrombus. In patients with grade V thrombus, thrombus aspiration was associated with significantly lower 6-month mortality or heart failure rehospitalization. In patients with lower thrombus burden, thrombus aspiration did not affect outcomes. HF, heart failure; TA, thrombus aspiration.

A similar trend in clinical course was observed after both propensity score matching and IPW adjustment. Standard mean differences between the 2 groups were mostly low after adjustment, except post-PCI SYNTAX score with an adjusted standard mean difference of −11.8 (). After matching, 6-month death or heart failure rehospitalization in the grade V thrombus group was still significantly lower in the TA group than in the no-TA group (HR: 0.68; 95%CI, 0.46-0.99; P=.05 after propensity score matching, HR: 0.70; 95%CI: 0.49-0.99; P=.04 after IPW adjustment; ).

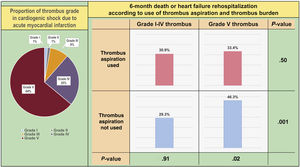

DISCUSSIONIn the present study, clinical efficacy of TA was investigated, and the differential prognostic implication of TA was assessed based on thrombus burden in patients with AMI complicated by CS. Overall, use of TA failed to show benefits regarding survival or risk of heart failure rehospitalization in patients with AMI complicated by CS. However, in selected patients with AMI complicated by CS and high thrombus burden (grade V), TA was associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause death or rehospitalization due to heart failure at 6 months compared with that of patients not receiving TA; this benefit of TA was not observed in patients with low thrombus burden (grade I-IV) (figure 4).

Central illustration. Overview of the clinical impact of high thrombus burden and thrombus aspiration in cardiogenic shock with acute myocardial infarction. High thrombus burden (grade V thrombus causing total coronary occlusion) is frequently encountered in cardiogenic shock due to ischemic cause and is associated with a higher incidence of adverse outcomes. When these patients with high thrombus burden are selected, thrombus aspiration seems to benefit their clinical course. The proportion of incidence is calculated as Kaplan-Meier estimates, with the significance level calculated by the log-rank test.

Embolization of atherothrombotic material during PCI causes blockage of distal vasculature, resulting in suboptimal reperfusion of viable myocardium, larger infarct size, and poorer prognosis.20 TA was developed to manually or mechanically reduce the amount of thrombi, preventing distal embolization and further improving myocardial perfusion and clinical outcomes.1 Based on the theoretical background, in prior small-sized randomized trials, TA was associated with better myocardial perfusion as evidenced by myocardial blush grade, ST-segment elevation resolution, and infarct size measured using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.3,4,7,21 In addition, the TAPAS trial, which enrolled 1071 patients with AMI showed routine use of TA to be associated with a significant reduction in mortality at the 1-year follow-up.5 Conversely, in the larger randomized TASTE (n=7244) and TOTAL (n=10,732) trials, routine TA during primary PCI for STEMI consistently did not reduce the risk of adverse cardiac events at both the 30-day and 1-year follow-ups.8,9,22,23 Therefore, the current guidelines do not recommend routine use of TA during primary PCI for patients with AMI (class III).11,18

Because patients with AMI complicated by CS generally have a higher thrombus burden with impaired myocardial perfusion than participants without CS, TA might be more beneficial in patients with AMI complicated by CS in terms of clinical outcomes. The present study cohort showed a higher thrombus grade (grade V, 368/575 patients, 64.0%) compared with a previous randomized trial (grade V, 6.2% in the TASTE trial). However, limited data are available on the efficacy of TA devices in the setting of primary PCI for patients with AMI complicated by CS because strict inclusion criteria in most of the randomized trials led to exclusion of high-risk CS patients; only 2 previous studies were conducted on the effects of TA in AMI patients with CS. In a small single-center study, a significantly lower in-hospital death was reported in patients treated with TA compared with participants treated with standard PCI,14 but another study with 155 patients concluded that TA was not an independent predictor of in-hospital and long-term survival.15 Similar to the results of previous randomized trials, significant differences were not found in the rates of in-hospital death, 6-month follow-up mortality, and rehospitalization due to heart failure in the present study based on the use of TA during primary PCI in 575 patients with AMI complicated by CS. This result indicates that application of TA during primary PCI might not be beneficial even in patients with AMI complicated by CS, in accordance with current guideline recommendations. Future well-designed randomized trials to identify the efficacy or safety of TA focusing on participants with AMI and CS are needed to confirm this finding.

Clinical benefit of thrombus aspiration for AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock and high thrombus burdenOne of the questions that remains regarding the effects of TA is the selection of patients who might benefit from the procedure. Patients with significant thrombus burden have been suggested to be good candidates for TA. In their 2013 meta-analysis, De Luca et al.24 argued that the benefits of myocardial perfusion after TA were significantly associated with the prevalence of coronary thrombus. In addition, Ge et al.25 reported that TA in patients with high thrombus burden could achieve long-term clinical outcomes similar to those of participants with low thrombus burden.25 However, in the high thrombus burden subgroup of the TOTAL trial, routine TA did not improve cardiovascular outcomes and was associated with an increased rate of stroke.26 Conversely, in the individual patient-level meta-analysis including TOTAL, TAPAS, and TASTE trials, the authors found that TA tended to be associated with reduced cardiovascular death and increased stroke in the high thrombus burden group.27 However, in that meta-analysis,27 only 0.8% of enrolled patients presented with Killip class IV, indicating that previous findings regarding the effects of TA in high thrombus burden cannot be extrapolated to patients with AMI complicated by CS. In the present study using a multicenter dedicated CS registry, TA during primary PCI was associated with reduced risk of all-cause death and heart failure rehospitalization at 6 months in AMI patients complicated by CS and high thrombus burden. This result was consistent after adjustment for the baseline differences, with significant interaction between thrombus grade and the use of TA for the primary outcome. The difference was still observed after propensity score matching and IPW adjustment.

Our findings support TA as more beneficial for patients with high thrombus burden than for those with low thrombus burden. Unlike AMI with hemodynamic stable conditions, low aortic pressure with impaired coronary perfusion and increased thrombogenicity in patients with AMI and CS might explain the discordance of effects for TA in high thrombus burden participants between the current study and previous randomized trials. Therefore, the use of TA to reduce absolute thrombus burden during primary PCI might be considered in selected patients with AMI complicated by CS and high thrombus burden to improve clinical outcomes. Naturally, CS is a complex condition that involves not only angiographic factors but also hemodynamic and clinical factors such as organ dysfunction, and use of TA may not completely explain the difference in clinical outcomes. However, the consistency of results throughout various adjustment methods suggests that there is at least a possibility TA might partially play a role in improving outcomes in selected CS patients complicating AMI. Further randomized trials will need to be designed to confirm these observations.

Of note, stroke was only observed in the TA group. Analysis the whole population showed a significantly higher incidence of stroke in the TA group than in the non-TA group. All 3 cases of stroke were ischemic and occurred within 7 days after the index procedure. Although it is difficult to discern the association between the use of TA and stroke, the timing of the events seemed to suggest that the strokes might be attributable to TA. This finding is supported by the higher incidence of stroke after the use of TA compared with its nonuse in the TOTAL trial.9 In addition, because shock patients are frequently under mechanical ventilation and analgosedative therapy, there is a possibility that the incidence of stroke is underreported. Therefore, although definite no conclusions can be drawn from this study, care should be taken after the use of TA because of its potential to cause stroke.

LimitationsThe present study has several limitations. Most of the limitations stem from the fact that this was a retrospective observational study. First, there were some differences in the baseline characteristics between the 2 groups, although these were adjusted in the analysis to some degree. Second, a previous study claimed thrombus grade on initial coronary angiography could be overestimated, and suggested that thrombus be properly graded after crossing the occlusion with a wire or small angioplasty balloon.28 This method could have helped us to provide a more accurate classification of thrombus and evaluation of the efficacy of TA but, due to retrospective nature of this study, the grading could only be done with initial coronary angiography. In addition, there were probably various unmeasured variables, apart from those included in this study, and because they could not have been included in our adjusted analysis with the Cox proportional hazards model, it may not fully predict the risk of outcomes with given factors. Likewise, because the use of TA was at the operator's discretion, TA could have been used more frequently by operators relatively more familiar with and skilled in the procedure. Information on the type of TA catheter (eg, mechanical or manual) was also unknown, and the effect of TA catheter selection on outcomes could not be analyzed. In addition, although the present study is the largest to assess the effects of TA on CS to date, the number of cases was small and the HR for several outcomes could not be accurately calculated. In particular, stroke was only observed in 3 patients and could have been underreported due to the inherent nature of shock patients and the use of mechanical ventilation with analgosedative therapy. Finally, the subgroup study with grade V thrombus was not a prespecified subgroup study for the CS registry used in our study, and therefore there is a chance that these findings were spurious. These types of limitation will be solved by a well-designed randomized prospective trial in the future.

CONCLUSIONSThe use of TA was not associated with an improvement in in-hospital and 6-month adverse cardiovascular events in patients with AMI complicated by CS. However, in selected patients with a high thrombus burden, specifically grade V thrombus, TA might have the potential to improve clinical outcomes. Further large-scale studies are warranted to confirm the results of the present study.

- –

In previous trials, routine thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for AMI did not reduce the risk of adverse cardiac events.

- –

The procedure has been further hampered by increased risk of stroke, leading clinical guidelines not to recommend its routine use.

- –

However, there is speculation that selected patients could benefit from the use of thrombus aspiration.

- –

Our study found that for AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock caused by high thrombus burden (grade V), thrombus aspiration may improve short- and mid-term clinical outcomes.

- –

Specifically, when patients with grade V thrombus–totally occluding thrombus–are selected, use of thrombus aspiration was associated with better in-hospital mortality and 6-month clinical outcomes.

- –

This group of patients may represent those who can benefit from the use thrombus aspiration to improve clinical outcomes.

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONK.H. Choi and J.H. Yang contributed to the conception and design of the study. W. Kwon and K.H. Choi prepared the initial manuscript and performed the statistical analysis. Y.J. Chung and W. Kwon organized the database. All remaining authors,T.K. Park, J.M. Lee, Y.B. Song, J.Y. Hahn, S.H. Choi, C.M. Ahn, C.W. Yu, I.H. Park, W.J. Jang, H.J. Kim, J.W. Bae, S.U. Kwon, H.J. Lee, W.S. Lee, J.O. Jeong, S.D. Park, and H.C. Gwon, performed the procedure and registered the initial data in the database. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and read, and approved the submitted version.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We especially thank Se Young Im, MS, Sang Man Park, MS, and Jimin Park, MS for their contribution in performing the angiographic core laboratory analysis.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2023.01.009