Right ventricular pacing has a deleterious effect on ventricular contraction that can lead to the development of pacing-induced cardiomyopathy.1

His bundle pacing is the most physiological method of permanent ventricular pacing. His bundle pacing has been demonstrated to reduce adverse events (cardiomyopathy, heart failure and mortality) compared with pacing of the right ventricular apex.2 There are several factors that limit the widespread use of His bundle pacing: a) progression of the block to distal zones, b) the rate of successful implantation, c) late threshold increase due to microdislocation,3 and d) patients whose block occurs in the most distal portion of the bundle of His.

Huang et al.4 recently demonstrated the feasibility of a physiological left bundle branch pacing (LBBP); this allows capture of the His-Purkinje system distal to the bundle of His with lower thresholds and better stability and detection. LBBP has been used successfully for ventricular pacing, as well as for the correction of left bundle branch block, as an alternative to cardiac resynchronization.5 However, the number of patients included in the publications was low, and there are no randomized trials.

In this article we report the effect of LBBP on electrocardiographic and echocardiographic variables in a consecutive series of patients with indication for conventional pacing or cardiac resynchronization therapy.

We included consecutive patients referred to our unit for implantation of a permanent cardiac pacing device. We excluded patients whose percentage of ventricular pacing was predicted to be low.

The pacing lead was implanted in the left bundle branch following the technique previously described by Huang et al.4 The lead used was the 3830-69 Select-Secure (Medtronic Inc, USA) and the catheter used was the C315His (Medtronic Inc, USA).

Lead position was checked on a left anterior oblique projection, and interventricular septum penetration was confirmed using iodinated contrast. The criteria described by Chen et al.6 were used to determine left bundle branch capture.

One operator, who was blinded, assessed LV function on echocardiography. This was performed once before implantation and repeated after at least 4 weeks. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated according to the Simpson method. Electrocardiograms performed with the multichannel recording system Cardiolab Prucka (GE Inc, USA) were collected. QRS duration (QRSd) was obtained before and after implantation. In all patients, the first follow-up was performed at 3 months after device implantation.

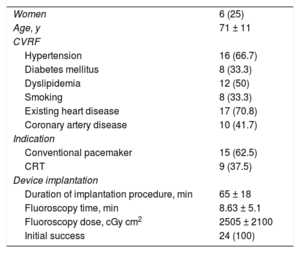

We included 24 consecutive patients who underwent implantation of an LBBP lead. Successful implantation was achieved in all patients (n = 24). The characteristics of the patients and the details of the procedure are given in table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample

| Women | 6 (25) |

| Age, y | 71 ± 11 |

| CVRF | |

| Hypertension | 16 (66.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (33.3) |

| Dyslipidemia | 12 (50) |

| Smoking | 8 (33.3) |

| Existing heart disease | 17 (70.8) |

| Coronary artery disease | 10 (41.7) |

| Indication | |

| Conventional pacemaker | 15 (62.5) |

| CRT | 9 (37.5) |

| Device implantation | |

| Duration of implantation procedure, min | 65 ± 18 |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 8.63 ± 5.1 |

| Fluoroscopy dose, cGy cm2 | 2505 ± 2100 |

| Initial success | 24 (100) |

CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; CVRF, cardiovascular risk factors.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

Analysis of the acute electrical parameters at the first follow-up showed no differences in threshold (0.58 ± 0.2 vs 0.57 ± 0.1 V in 0.4 ms; P = .988) or ventricular detection (13.6 ± 7 vs 13.5 ± 5 mV; P = .978). No patient showed a sudden increase in threshold or change in impedance that would require lead revision or replacement.

At baseline, the mean QRS width was 150 ± 24ms. The LBBP achieved a significant reduction in QRS width, both when analyzing all the patients in the sample (150 ± 24 vs 105 ± 11 ms; P = .012) and when analyzing only the 19 patients with prolonged QRS at baseline (158.2 ± 21 vs 106.8 ± 12 ms; P < .001). In the 5 patients with narrow QRS at baseline (≤ 120ms) there were no significant differences between groups (107.5 ± 11 vs 102.4 ± 4 ms; P = .44).

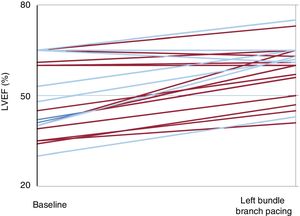

Echocardiography was performed at 63 ± 20 days after implantation to analyze hemodynamic parameters (figure 1). LBBP achieved a significant increase in LVEF (50.8% ± 13% vs 58.3% ± 9%; P < .001). In the 9 patients with dyssynchrony (left bundle branch block or pacing-associated cardiomyopathy) there was an even greater increase compared with baseline (38.5% ± 4% vs 53.4% ± 9%; P < 0.001). Patients with a preserved LVEF and those without an underlying dyssynchrony (n = 15) showed no differences in LVEF between baseline and after implantation (58.3% ± 11% vs 61% ± 9%; P = .1).

This study is the first published series on deep septal pacing in a Spanish hospital. It demonstrates that LBBP is feasible in most patients in whom it is attempted and is not associated with an increase in complications. The rate of successful implantation, the duration of the implantation procedure and the fluoroscopy dose are similar to those previously published by other groups.5

LBBP does not have a deleterious effect on LVEF in the short- to mid-term, either in patients with preserved LVEF or in those with reduced LVEF and need for permanent ventricular pacing. Indeed, for patients with reduced LVEF associated with a ventricular dyssynchrony phenomenon (ventricular dysfunction due to ventricular pacing or left bundle branch block), LBBP has a beneficial effect on the LVEF and even normalizes it in a good number of patients.