Frailty is a common syndrome in older patients with heart failure (HF) and is characterized by decreased functional reserve and associated risks of disability, hospitalization, and death.1 Exercise rehabilitation programs have been demonstrated to improve the functionality of patients with HF.2,3 However, the implementation of these structured programs is hindered by certain barriers. The REHAB-HF trial2 improved Short Physical Portable Battery (SPPB) scores in 349 frail patients randomized after an acute HF episode. In the trial, patients attended 3 in-person weekly sessions for 12 weeks.

Although this protocol might seem ideal, its implementation in the real world is hampered by the resources needed. Another obstacle to the implementation of in-person treatments is the need for patients to travel from home, especially in older patients in suburban or rural areas. Furthermore, the patients studied were significantly younger than those in usual clinical practice in cardiogeriatrics and therefore the results of these clinical trials cannot be directly extrapolated to frail older patients.

Some exercise programs have been adapted to frail older patients, such as the Vivifrail program.4 These programs have been shown to improve outcomes in these patients,5 but have not been studied in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). The Vivifrail program individualizes the type, frequency, and intensity of exercises to the functional characteristics and estimated risk of falls in each patient and can be performed at home, with 5 sessions per week, overcoming the limitations of conventional cardiac rehabilitation in frail older patients.

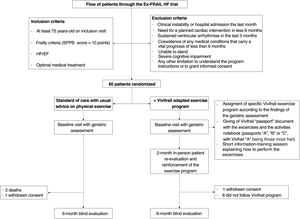

The Ex-FRAIL-HF randomized controlled single-blind intervention trial analyzed the benefit of Vivifrail in elderly patients with HFrEF and frailty criteria during a 6-month period. The flowchart for the study is shown in figure 1. After approval from the regional ethics committee of Galicia, the study was conducted by the Cardiology Department and Geriatric Medicine Department of the Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo. This is a parallel group study with a 1:1 ratio between the intervention and control groups and with blind evaluation of the outcome variables. Included patients were aged at least 75 years, with SPPB<10 points, and had a diagnosis of HFrEF. Following other experiences in the literature,6 we included 60 patients in this pilot study. After signing the informed consent form, patients were recruited between May 2021 and May 2022 and the last follow-up was in November 2022. All patients underwent a comprehensive geriatric assessment, which was carried out again at 6 months. The effects of the Vivifrail program on functional status, quality of life and frailty were analyzed. As a safety and exploratory analysis, we also analyzed clinical variables.

Patients randomized to the intervention group were offered the possibility of following the Vivifrail program. The assignment of the individualized exercise (included in each different Vivifrail “passport” document: “A”, “B” or “C”, with Vivifrail passport A including the most frail patients) was selected according to the findings of the baseline assessment. After a short information and training session, the patients were given the Vivifrail “passport” document. Like the control group, patients in the intervention group also received standard self-management guidelines for HF, including general advice on physical activity. The intervention was performed for 6 months, with patient re-evaluation and reinforcement at 2 months. Adherence to the exercise prescribed in the Vivifrail group was monitored using the diary of activities included with the Vivifrail passport as well as patients’ self-reports. Patients were considered nonadherent when the diary of activities was completely empty and they self-reported that they did not follow the program at all. Both criteria were necessary.

A total of 60 patients (30 from each group) were included in the study; 2 patients died before the 6-month visit (both from the control group) and another 2 patients (1 from each group) refused to attend the 6-month visit because of the COVID-19 pandemic and were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 56 patients, 27 were in the control group and 29 were in the intervention group. Of the latter, 8 patients reported that they never followed the Vivifrail exercises. They were considered nonadherent and were excluded from the analysis as per protocol.

Finally, we analyzed 27 patients in the control group and 21 in the intervention group. The baseline characteristics and 6 month follow-up evaluation are summarized in table 1. Patients allocated to the Vivifrail exercise program significantly improved their New York Heart Association (NYHA) class compared with control group (improved NYHA by at least 1 point 47.6% vs 22.2% respectively; P=.04) and physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE) score (+6.4 vs−12.5; P=.004). Of those who improved NYHA class, most had NYHA III at baseline compared with NYHA II (60% vs 40%; P=.037). The Vivifrail group showed no statistically significant improvements in the other functional indicators measured compared with standard treatment, although some indicators were more numerically favorable in the Vivifrail group: nonfrail status with SPPB higher than 9 points (Vivifrail 38.1% vs 22.2% control; P=.13), improved Katz index (Vivifrail 23.8% vs 18.5% control; P=.65), 6-minute walk test (6MWT) change compared with baseline (% change; Vivifrail+3.24% vs−4.98% control; P=.37), and quality of life as indicated by the Minnesotta Living with Heart Failure (MLWHF) questionnaire (Vivifrail−3.81 vs−1.33 control; P=.45). Clinical events were also recorded for the exploratory analysis. In addition to the 2 deaths due to HF progression in the control group, 2 patients in the control group and another 2 patients in the Vivifrail group required hospital admission or an unplanned visit due to HF progression during the study period. No falls requiring medical assistance were reported in the Vivifrail or control groups.

Baseline characteristics of the EX-FRAIL HF population and 6-month re-evaluation

| Baseline characteristics | Control group | Intervention group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline evaluation | |||

| Age, y | 82.6±5.7 | 83.2±5.1 | .72 |

| Hypertension | 25 (92.6) | 16 (76.2) | .11 |

| Diabetes | 9 (33.3) | 12 (57.1) | .10 |

| Dyslipidemia | 18 (66.7) | 12 (57.1) | .49 |

| LVEF, % | 34.5±5.1 | 31.1±7.4 | .07 |

| Treatment on inclusion | |||

| Beta-blockers | 22 (81.5) | 17 (81) | .96 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 6 (22.2) | 3 (14.3) | .79 |

| ARNI | 20 (74.1) | 18 (85.7) | .32 |

| iSGLT2 | 10 (37) | 9 (42.9) | .68 |

| MRA | 11 (41) | 9 (43) | .74 |

| Loop diuretics | 20 (74.1) | 12 (57.1) | .21 |

| Oral anticoagulants | 23 (85.2) | 15 (71.4) | .24 |

| ICD | 4 (14.8) | 1 (4.8) | .25 |

| CRT | 4 (14.8) | 3 (14.3) | .96 |

| Pacemaker | 2 (7.4) | 4 (19) | .22 |

| Examination | |||

| SBP, mmHg | 121.7±17.8 | 122.7±17.0 | .85 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 68.8±11.2 | 67.7±10.8 | .72 |

| Body mass index | 28.4±4.7 | 29.9±5.3 | .30 |

| Blood tests | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.6±2.1 | 13.8±1.6 | .67 |

| GFR, mL/min/m2 | 50.4±1.6 | 38.8±28.5 | .16 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 140.8±2.2 | 140.5±2.0 | .68 |

| NT-ProBNP, pg/mL (median) | 1409 | 1257 | .97 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 150.3±45.6 | 161.0±35.9 | .41 |

| Functionality on inclusion | |||

| SPPB, points | 6.3±1.9 | 6.5±2.1 | .75 |

| NYHA I | 9 (33) | 3 (14) | .24 |

| NYHA II | 14 (52) | 12 (57) | .24 |

| NYHA III | 4 (15) | 6 (29) | .24 |

| PASE score, points | 38.5±23.6 | 28.1±3.5 | .11 |

| Katz index A | 19 (70.4) | 11 (52.4) | .50 |

| Katz index B | 4 (14.8) | 6 (28.6) | .50 |

| Katz index C | 1 (3.7) | 2 (9.5) | .50 |

| Katz index D | 3 (11.1) | 2 (9.5) | .50 |

| Barthel index, points | 93.7±11.2 | 92.1±10.7 | .63 |

| Frield frail/prefrail | 18/9 (66.7/33.3) | 12/9 (57/43) | .64 |

| Lawton-Brody index, points | 5.1±2.4 | 4.67±2.4 | .53 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale, points | 3.9±2.1 | 3.7±2.2 | .69 |

| MLWHF, points | 11.6±12.2 | 11.2±11.0 | .91 |

| 6MWT, m | 246±106 | 269±112 | .49 |

| Functionality at 6 months of follow-up | |||

| SPPB, points | 7.27 | 7.71 | .64 |

| SPPB above 9 | 6 (22.2) | 8 (38.1) | .13 |

| NYHA I | 11 (41) | 7 (33) | .82 |

| NYHA II | 13 (48) | 12 (57) | .82 |

| NYHA III | 3 (11) | 2 (10) | .82 |

| NYHA improvement | 6 (22.2) | 10 (47.6) | .04 |

| PASE score* | −12.5 | 6.4 | .004 |

| Katz index A | 16 (61.5) | 12 (57.1) | .60 |

| Katz index B | 6 (23.1) | 3 (14.3) | .60 |

| Katz index C | 1 (3.8) | 2 (9.5) | .60 |

| Katz index D | 2 (7.7) | 3 (14.3) | .60 |

| Katz index E | 1 (3.8) | 1 (4.8) | .60 |

| Katz improvement | 18.5 | 23.8 | .65 |

| Barthel,* points | −3.14 | −3.1 | .98 |

| Lawton-Brody,* points | −0.4 | −0.52 | .77 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale,* points | 0.04 | −0.14 | .78 |

| MLWHF,* points | −1.33 | −3.81 | .45 |

| 6MWT,* m | −14.2 | 2.26 | .55 |

| 6MWT change, m | −4.98 | 3.24 | .37 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MLWHF, Minnesotta Living with Heart Failure; 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-ProBNP, N-Terminal probrain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PASE, physical activity scale for the elderly; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor; SPPB, short physical performance battery.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range] unless otherwise indicated.

Patients who reported they were nonadherent to the Vivifrail program did not have more advanced HF nor were they more frail: the proportion of patients with A and B Vivifrail passports was the same in the 2 groups (87.5% in nonadherent vs 85.7% in adherent; P=.77), as was functional class III (25% vs 28.6%; P=.48), left ventricular ejection fraction (32.6%±6.9 vs 31.1±7.4%; P=.61), SPPB (7.4±2.3 vs 6.5±2.1; P=.21), PASE score (40.1±31.9 vs 28.1±17.9; P=.34), Barthel score (90.6±17.8 vs 92.1±10.7; P=.77), and 6MWT (308±128 vs 269±112; P=.44). Nonadherent patients showed worse depression (Geriatric Depression Scale, 6.0±1.9 vs 3.7±2.2; P=.01) and quality of life scores (MLWHF, 20.7±14.2 vs 11.2±11.0; P=.07), which might have hampered adherence to the exercise prescribed.

This pilot study shows that the Vivifrail program improved NYHA and PASE score in frail older patients with HFrEF in 6 months. A multicenter study would be desirable to confirm these findings as well as testing Vivifrail in a larger sample to better understand its effect on the other functional and quality of life parameters analyzed. The Ex-FRAIL-HF approach could be considered more pragmatic and easier to implement in the real world of constrained resources than other in-hospital programs. Another finding is that one-third of the patients randomized to the exercise program did not perform the exercises prescribed. These patients did not have a worse HF profile, but showed significantly worse depression scores, which has also been linked to worse HF drug adherence and prognosis. This finding highlights that depression should be actively investigated and adequately addressed to improve patient adherence to treatments.

FUNDINGThis study was funded with an unconditional grant from the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SECAINC-INV-ICC 20/002).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSStudy design: D. Dobarro, M. Cordeiro-Rodríguez, and C. Rodríguez-Pascual. Inclusion and study procedures: A. Costas-Vila and M. Melendo-Viu. Analysis and writing: D. Dobarro and M. Melendo-Viu. Proofreading: C. Rodríguez Pascual and A. Íñiguez-Romo.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.