Heart failure (HF) is a complex syndrome. Its incidence is 2% in the European adult population but increases with age, affecting more than 10% of individuals older than 70 years.1 In Spain, hospital attendance due to HF has increased as a result of population aging and, although the crude rate of in-hospital mortality has fallen, no significant differences are found after adjustment for risk.2

The care outcomes for patients hospitalized for HF in Spain have been investigated using clinical registries and administrative databases (ADs), such as the Registry of specialized healthcare activity-minimum data set (RSHCA-MDS),2 the largest source for the study of in-hospital mortality. ADs are appropriate for studying health care outcomes because they offer longitudinal data on large populations and are readily obtained, but their usefulness depends on the accuracy of the data record, which is largely related to the quality of the diagnostic and procedural coding.

The usefulness of ADs for the study of HF has been internationally compared,3 and the RSHCA-MDS has been used in Spain for investigating the outcomes of patients admitted for HF. Nonetheless, little information is available on its validity for this objective. To assess the implications of its use for this purpose in the Spanish National Health System, we adopted as a comparative reference the Heart Failure Registry of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ICC-SEC).4 The objective of this registry is to analyze the impact of adherence to the recommendations of Spanish Society of Cardiology guidelines on HF1 and includes patients with a confirmed diagnosis of HF and admission to a HF unit in the cardiology department of a hospital with SEC EXCELENTE accreditation5 in the HF process.

Because ICC-SEC and RSHCA-MBDS have different data models and scopes (ICC-SEC includes outpatient follow-up, unlike RSHCA-MDS) and because both registries lack shared attributes that would permit unambiguous matching of records corresponding to a single event (direct identifiers), we used indirect identifiers—birth date, admission date, sex, and treating hospital—to match events recorded in the 2 sources in 2019 and 2020. As a sensitivity analysis, the matching was widened by allowing differences of up to ± 2 days in birth and admission dates.

To assess the validity of the diagnoses coded in the RSHCA-MDS, we selected some of the most relevant variables for the risk adjustment of in-hospital mortality due to HF and calculated the main indicators of accuracy and concordance.

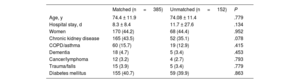

Of the 671 patients recorded in the ICC-SEC, 134 were excluded (20%): 109 (16.2%) because they were outpatients and 25 (3.7%) due to data inconsistencies. Of the 537 remaining patients, 385 could be matched (71.7%, mean age, 74.39 ± 11.83 years); 170 (44.2%) were women. No differences were found in age, length of hospital stay, or comorbidity profile between matched and unmatched patients (table 1). The crude rates of in-hospital mortality were 3.38% in the ICC-SEC and 3.12% in the RSHCA-MDS (P=.999).

Profiles of matched and unmatched patients

| Matched (n = 385) | Unmatched (n = 152) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 74.4 ± 11.9 | 74.08 ± 11.4 | .779 |

| Hospital stay, d | 8.3 ± 8.4 | 11.7 ± 27.6 | .134 |

| Women | 170 (44.2) | 68 (44.4) | .952 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 165 (43.5) | 52 (35.1) | .078 |

| COPD/asthma | 60 (15.7) | 19 (12.9) | .415 |

| Dementia | 18 (4.7) | 5 (3.4) | .453 |

| Cancer/lymphoma | 12 (3.2) | 4 (2.7) | .793 |

| Trauma/falls | 15 (3.9) | 5 (3.4) | .779 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 155 (40.7) | 59 (39.9) | .863 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation or No. (%).

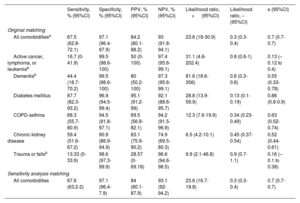

Accuracy and concordance indicators are shown in table 2. Taken together, the comorbidities studied showed acceptable sensitivity, very high specificity, and substantial concordance. Considered separately, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-asthma, and chronic kidney disease displayed better validity indices than the other 3 comorbidities (all with incidence rates < 5% in both registries). The concordance was insignificant for active cancer, lymphoma, and leukemia and for trauma and falls, moderate for dementia and chronic kidney disease, and almost perfect for diabetes mellitus. In the sensitivity analysis, 413 patients could be matched (76.9%) and the results were similar (table 2).

Validity and concordance indicators for the comorbidities studied

| Sensitivity, % (95%CI) | Specificity, % (95%CI) | PPV, % (95%CI) | NPV, % (95%CI) | Likelihood ratio, + (95%CI) | Likelihood ratio, – (95%CI) | κ (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original matching | |||||||

| All comorbiditiesa | 67.5 (62.8-72.1) | 97.1 (96.4-97.9) | 84.2 (80.1-88.2) | 93 (91.8-94.1) | 23.6 (18-30.9) | 0.3 (0.3-0.4) | 0.7 (0.7-0.7) |

| Active cancer, lymphoma, or leukemiab | 16.7 (0-41.9) | 99.5 (98.6-100) | 50 (0-100) | 97.4 (95.6-99.1) | 31.1 (4.8-202.4) | 0.8 (0.6-1) | 0.13 (–0.12 to 0.4) |

| Dementiab | 44.4 (18.7-70.2) | 99.5 (98.6-100) | 80 (50.2-100) | 97.3 (95.6-99.1) | 81.6 (18.6-356) | 0.6 (0.3-0.8) | 0.55 (0.33-0.78) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 87.7 (82.3-93.2) | 96.9 (94.5-99.4) | 95.1 (91.2-99) | 92.1 (88.6-95.7) | 28.8 (13.9-59.9) | 0.13 (0.1-0.19) | 0.86 (0.8-0.9) |

| COPD-asthma | 68.3 (55.7-80.9) | 94.5 (91.8-97.1) | 69.5 (56.9-82.1) | 94.2 (91.5-96.9) | 12.3 (7.6-19.9) | 0.34 (0.23-0.49) | 0.63 (0.52-0.74) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 59.4 (51.6-67.2) | 90.9 (86.9-94.9) | 83.1 (75.9-90.2) | 74.9 (69.5-80.3) | 6.5 (4.2-10.1) | 0.45 (0.37-0.54) | 0.52 (0.44-0.61) |

| Trauma or fallsb | 13.33 (0-33.9) | 98.6 (97.3-99.9) | 28.57 (0-69.18) | 96.6 (94.6-98.5) | 9.9 (2.1-46.8) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 0.16 (–0.1 to 0.38) |

| Sensitivity analysis matching | |||||||

| All comorbidities | 67.6 (63.2-2) | 97.1 (96.4-7.9) | 84 (80.1-87.9) | 93.1 (92-94.2) | 23.6 (16.7-19.8) | 0.3 (0.3-0.4) | 0.7 (0.7-0.7) |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Although the failed matches are the main limitation of our study, we achieved considerably greater matching (71.7% vs 60.8%) than a previous study6 of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) that used the DIOCLES clinical registry as reference; while our sensitivity (67.5% vs 85.1%) and concordance (κ=.7 vs κ=.86) were lower, our specificity was similar (97.1% vs 98.3%). These results indicate that the validity and concordance of the variables relevant for the adjustment of risk of HF events recorded in the RSHCA-MDS are generally reasonable and are in line with the expected results in ADs,5 although somewhat lower than those found for ACS.

Our consideration of variables with very low incidence rates could partly explain the slightly lower validity and concordance for HF than previously found for ACS. However, independently of this factor, adjustments by risk of in-hospital mortality and readmission are usually worse for HF than for ACS. Accordingly, measures should be adopted to improve the recording and coding of HF events in the RSHCA-MDS, particularly for comorbidities with lower incidences.

FUNDINGThis work has not received any external funding.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSStudy design and manuscript drafting: J.L. Bernal, J. Elola, and M. Anguita. Data revision and statistical analysis: J.L. Bernal and N. Rosillo. Revision, editing, and manuscript approval: all authors.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors report no conflicts of interest associated with this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSWe thank the Spanish Ministry of Health for granting access to the MBDS database and the Institute of Health Information of the Spanish National Health System for the facilities provided to the Spanish Society of Cardiology to undertake the RECALCAR project.