Coronary artery calcium (CAC) score improves the accuracy of risk stratification for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events compared with traditional cardiovascular risk factors. We evaluated the interaction of coronary atherosclerotic burden as determined by the CAC score with the prognostic benefit of lipid-lowering therapies in the primary prevention setting.

MethodsWe reviewed the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases for studies including individuals without a previous ASCVD event who underwent CAC score assessment and for whom lipid-lowering therapy status stratified by CAC values was available. The primary outcome was ASCVD. The pooled effect of lipid-lowering therapy on outcomes stratified by CAC groups (0, 1-100,> 100) was evaluated using a random effects model.

ResultsFive studies (1 randomized, 2 prospective cohort, 2 retrospective) were included encompassing 35 640 individuals (female 38.1%) with a median age of 62.2 [range, 49.6-68.9] years, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of 128 (114-146) mg/dL, and follow-up of 4.3 (2.3-11.1) years. ASCVD occurrence increased steadily across growing CAC strata, both in patients with and without lipid-lowering therapy. Comparing patients with (34.9%) and without (65.1%) treatment exposure, lipid-lowering therapy was associated with reduced occurrence of ASCVD in patients with CAC> 100 (OR, 0.70; 95%CI, 0.53-0.92), but not in patients with CAC 1-100 or CAC 0. Results were consistent when only adjusted data were pooled.

ConclusionsAmong individuals without a previous ASCVD, a CAC score> 100 identifies individuals most likely to benefit from lipid-lowering therapy, while undetectable CAC suggests no treatment benefit.

Keywords

Lipid-lowering therapy improves cardiovascular outcomes among patients with a prior atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event.1 Hence, lipid-lowering therapy is universally recommended for the secondary prevention of ASCVD.2

In the primary prevention setting, lipid-lowering therapy reduces ASCVD occurrence.1,3 However, the absolute risk reduction in the overall population may be offset by adverse effects, cost-benefit considerations, and clinical disutility. Identification of high-risk patients is thus pivotal to ensure clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness when prescribing lipid-lowering therapy in asymptomatic individuals.

Risk factor matrices developed from epidemiological studies have only moderate ability to predict ASCVD,4,5 as there is substantial heterogeneity between clinical risk and actual atherosclerotic burden.5,6 Coronary artery calcium (CAC) is a highly specific marker of atherosclerotic burden,7 able to improve ASCVD prediction among asymptomatic individuals over traditional risk factors.6,8–10 Patients with no detectable CAC are at very low risk of ASCVD events, suggesting that the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy may be trivial in this subset.8 However, the relative impact of lipid-lowering therapies on de novo ASCVD occurrence, as stratified by increasing CAC values, remains poorly characterized. For this reason, recommendations by the European Society of Cardiology regarding CAC use to drive lipid-lowering therapy remain weak and a statement has been made on the need to further investigate the incremental value of reclassifying total cardiovascular risk and defining eligibility for lipid-lowering therapy based on CAC score.11

We thus performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the interaction of the coronary atherosclerotic burden as determined by the CAC score with the prognostic benefit of lipid-lowering therapies in the primary prevention setting.

METHODSStudy designThis meta-analysis was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement; the PRISMA checklist is available in the .12 The original study protocol was prospectively submitted for registration in PROSPERO and protocol amendments have been updated (registration code CRD42020171930).

All published clinical studies including patients without a previous ASCVD who underwent CAC score assessment were evaluated for inclusion in this meta-analysis. We considered for inclusion randomized clinical trials (RCT) or observational studies reporting ASCVD outcomes (defined as a composite endpoint including at least myocardial infarction or a proxy for myocardial infarction such as coronary revascularization) and lipid-lowering therapy status stratified by CAC values. Studies reporting the main study outcomes described in insufficient detail or not written in the English language were excluded. The main study outcome was ASCVD occurrence at last follow-up. ASCVD definition for each included study is reported in table 1. Patients were categorized by CAC strata (CAC 0, CAC 1-100, CAC> 100) and by lipid-lowering therapy status (yes vs no). The impact of lipid-lowering therapies on ASCVD occurrence stratified by CAC categories was evaluated. The ASCVD risk stratification ability of CAC score, overall and stratified by lipid-lowering therapy status was also evaluated.

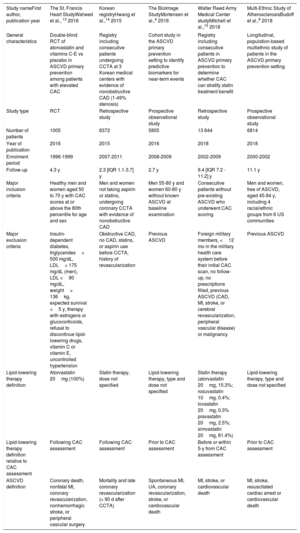

General characteristics of the included studies

| Study nameFirst author, publication year | The St. Francis Heart StudyWaheed et al., 13 2016 | Korean registryHwang et al.,14 2015 | The BioImage StudyMortensen et al.,4 2016 | Walter Reed Army Medical Center studyMitchell et al.,15 2018 | Multi-Ethnic Study of AtherosclerosisBudoff et al.,9 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | Double-blind RCT of atorvastatin and vitamins C-E vs placebo in ASCVD primary prevention among patients with elevated CAC | Registry including consecutive patients undergoing CCTA at 3 Korean medical centers with evidence of nonobstructive CAD (1-49% stenosis) | Cohort study in the ASCVD primary prevention setting to identify predictive biomarkers for near-term events | Registry including consecutive patients in ASCVD primary prevention to determine whether CAC can stratify statin treatment benefit | Longitudinal, population-based multiethnic study of patients in the ASCVD primary prevention setting |

| Study type | RCT | Retrospective study | Prospective observational study | Retrospective study | Prospective observational study |

| Number of patients | 1005 | 8372 | 5805 | 13 644 | 6814 |

| Year of publication | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | 2018 | 2018 |

| Enrolment period | 1996-1999 | 2007-2011 | 2008-2009 | 2002-2009 | 2000-2002 |

| Follow-up | 4.3 y | 2.3 [IQR 1.1-3.7] y | 2.7 y | 9.4 [IQR 7.2 - 11.2] y | 11.1 y |

| Major inclusion criteria | Healthy men and women aged 50 to 70 y with CAC scores at or above the 80th percentile for age and sex | Men and women not taking aspirin or statins, undergoing coronary CCTA with evidence of nonobstructive CAD | Men 55-80 y and women 60-80 y without known ASCVD at baseline examination | Consecutive patients without pre-existing ASCVD who underwent CAC scoring | Men and women, free of ASCVD, aged 45-84 y, including 4 racial/ethnic groups from 6 US communities |

| Major exclusion criteria | Insulin-dependent diabetes, triglycerides> 500 mg/dL, LDL> 175 mg/dL (men), LDL <90 mg/dL, weight> 136kg, expected survival <5 y, therapy with estrogens or glucocorticoids, refusal to discontinue lipid-lowering drugs, vitamin C or vitamin E, uncontrolled hypertension | Obstructive CAD, no CAD, statins, or aspirin use before CCTA, history of revascularization | Previous ASCVD | Foreign military members, <12 mo in the military health care system before their initial CAC scan, no follow-up, no prescriptions filled, previous ASCVD (CAD, MI, stroke, or cerebral revascularization, peripheral vascular disease) or malignancy | Previous ASCVD |

| Lipid-lowering therapy definition | Atorvastatin 20mg (100%) | Statin therapy, dose not specified | Lipid-lowering therapy, type and dose not specified | Statin therapy (atorvastatin 20mg, 15.3%; rosuvastatin 10mg, 0.4%; lovastatin 20mg, 0.3% pravastatin 20mg, 2.5%; simvastatin 20mg, 81.4%) | Lipid-lowering therapy, type and dose not specified |

| Lipid-lowering therapy definition relative to CAC assessment | Following CAC assessment | Following CAC assessment | Prior to CAC assessment | Before or within 5-y from CAC assessment | Prior to CAC assessment |

| ASCVD definition | Coronary death, nonfatal MI, coronary revascularization, nonhemorrhagic stroke, or peripheral vascular surgery | Mortality and late coronary revascularization (> 90 d after CCTA) | Spontaneous MI, UA, coronary revascularization, stroke, or cardiovascular death | MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death | MI, stroke, resuscitated cardiac arrest or cardiovascular death |

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CAC, coronary artery calcium; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; IQR, interquartile range; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MI, myocardial infarction; RCT, randomized controlled trial; UA, unstable angina.

Five authors (E. Elia, F. Bruno, F. Angelini, G. Gallone, and P.P. Bocchino) independently searched EMBASE, MEDLINE/PubMed, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) using a combination of the following free-text words: “calcium artery score”, “calcium score”, “CAC”, “statin”, “lipid lowering”, “preventive therapy” (detailed search strategy in the ) from inception to June 15, 2021. Backward snowballing was also performed (no additional studies found).

All authors independently assessed identified studies for possible inclusion. Nonrelevant articles were excluded based on the title and abstract. Two investigators (U. Annone, and F. Piroli) independently extracted data on study designs, measurements, patient characteristics, and outcomes using a standardized data extraction form. Conflicts regarding inclusion and data extraction were discussed and resolved with another investigator (L. Franchin). Data collection included authors, year of publication, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, baseline clinical features of patients, observed adverse events, and medical treatment, as available. To improve data extraction, and pertinent substudies were also examined.

Two independent reviewers (M. Bertaina, and E. Elia) assessed the risk of bias (low, intermediate, or high) of the included studies following the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommendations.16

Data synthesis and analysisThe analysis was by aggregate data. Cumulative event rates for study endpoints were obtained and reported. Pooled effect estimates of the outcomes were calculated as the weighted mean difference using a random effects model and are presented with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Subgroup analysis was performed including only RCTs and studies with multivariate adjustment. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using Cochrane Q statistics and I2 values. I2 values of less than 25% indicate low heterogeneity, 25% to 50% moderate heterogeneity, and greater than 50% high heterogeneity. Statistical significance was set at P <.05 (2-sided). Statistical analyses were conducted with RevMan 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

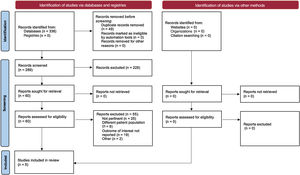

RESULTSA search of electronic databases, from inception March 1, 2020, identified a total of 276 records. Of these, a total of 5 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria, for an overall population of 35 640 patients4,9,13–15,17 (outcome data available for 97.4% of the study population). The consort diagram is shown in figure 1. The PRISMA checklist is provided in the . The bias assessment for each RCT is shown in .

A summary of included studies is available in table 1 and detailed baseline characteristics are reported in table 2. Of the included studies, 1 was an RCT, 2 were prospective cohort studies, and 2 were retrospective studies. Publication year ranged from 2015 to 2018 and study sample size from 1055 to 13 644 patients, with an overall female prevalence of 38.1%. Study follow-up ranged between 2.3 and 11.1 years. Median age ranged from 49.6 to 68.9 years and median low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ranged between 114.2 and 146.4mg/dL. Patients on lipid-lowering therapy accounted for between 23.7% and 50.5% (overall 34.9% of the study population). Two studies included patients with CAC> 0 exclusively. Overall, 14 612 (42.1%) patients had CAC 0, 12 166 (35.1%) patients had CAC 1-100 and 7909 (22.8%) patients had CAC> 100.

Baseline characteristics of the study populations overall and stratified by lipid-lowering therapy status

| Study Name First author, publication year | The St. Francis Heart Study Waheed et al.,13 2016 | Korean registry Hwang et al.,14 2015 | The BioImage Study Mortensen et al.,4 2016 | Walter Reed Army Medical Center study Mitchell et al.,15 2018 | Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Budoff et al.,9 2018 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=990) | L-L drugs (n=481) | Non-L-L drugs (n=509) | Overall (N=8372) | L-L drugs (n=1983) | Non-L-L drugs (n=6389) | Overall (N=5805) | L-L drugs (n=1991) | Non-L-L drugs (n=3814) | Overall (N=13644) | L-L drugs (n=6886) | Non-L-L drugs (n=6758) | Overall (N=6783) | L-L drugs (n=1101) | Non-L-L drugs (n=5657) | |

| Age, y | 58.9 | 60.0 | 58.9 | 61.4±10.9 | 62.6±10.3 | 61.0±11.1 | 68.9±6.0 | 70.1 | 68.6±6.0 | 49.6 | 51.1±8.9 | 48.1±7.6 | 62.2 | - | - |

| Female sex | 26.2 | 26.4 | 26.1 | 29.7 | 34.1 | 28.3 | 56 | 39.1 | 65.0 | 29.4 | 24.9 | 34 | 52.4 | - | - |

| Hyperlipidemia | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 49.5 | 75.0 | 23.5 | - | - | - |

| Lipid profile | |||||||||||||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 225.5 | 224.3±35 | 226.6±34 | 194.2 (41.3) | 207.5 (45.0) | 189.9 (39.1) | 202.5 (38.6) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 143.4 | 137.1±83 | 149.3±97 | 137.1 (87.2) | 133.5 (68.5) | 148.0 (88.5) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| LDL mg/dL | 146.4 | 146.1±30 | 146.7±30 | 116.6 (30.3) | 126.0 (32.6) | 113.6 (23.9) | 114.2 (33.2) | - | - | - | - | - | 140.3 | - | - |

| HDL mg/dL | 50.3 | 50.7±15 | 50±14 | 50.4 (12.5) | 50.5 (12.4) | 50.4 (12.5) | 55.7 (15.3) | - | - | - | - | 51.2 | - | - | |

| Hypertension | 31.6 | 30.6 | 32.6 | 31.3 | 47.0 | 26.4 | 62 | 70.3 | 58.0 | 34.0 | 45.1 | 22.8 | - | - | - |

| Diabetes | 7.1 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 15.2 | 24.6 | 12.3 | 15 | 24.8 | 10.0 | 6.8 | 10.0 | 3.6 | - | - | - |

| Current smoker/tobacco use | 67.2 | 67.6 | 66.8 | - | - | - | 9 | 9 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 5.3 | 13.1 | - | - |

| CAC score | |||||||||||||||

| CAC score | 374.4 | 379 [148-636] | 370 [183-671] | 94.1±221.5 | 90.4±218.0 | 106.1±232.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1852 (32.0) | 495 (24.9) | 1352 (35.4) | 9360 (68.6) | 3742 (54.3) | 4855 (83.1) | 3400 (50.2) | 361 (32.8) | 3029 (53.5) |

| 1-100 | 95 (9.6) | 44 (9.1) | 51 (10.2) | 5755 (76.9) | 1265 (74.8) | 4490 (77.5) | 1675 (29.0) | 582 (29.2) | 1089 (28.6) | 2877 (21.1) | 1081 (28.1) | 945 (14.0) | 1787 (26.3) | 348 (31.6) | 1437 (25.4) |

| > 100 | 895 (90.4) | 437 (90.0) | 458 (90.3) | 1733 (23.1) | 426 (25.2) | 1307 (22.5) | 2278 (39.0) | 914 (45.9) | 1367 (35.8) | 1407 (10.3) | 1211 (17.6) | 196 (2.9) | 1596 (23.5) | 390 (35.6) | 1201 (20.1) |

| Therapy | |||||||||||||||

| Lipid-lowering therapy | 48.6 | 100 | 0 | 23.7 | 100 | 0 | 34 | 100 | 0 | 50.5 | 100 | 0 | - | 100 | 0 |

| Aspirin | 100 | 100 | 100 | 44.8 | 66.1 | 35.1 | - | - | - | 16.0 | 24.8 | 7 | - | - | - |

| ACEI/ARB | - | - | - | 17.1 | 28.1 | 13.7 | - | - | - | 15.4 | 22.9 | 7.7 | - | - | - |

| Beta-blocker | - | - | - | 10 | 16.1 | 8.1 | - | - | - | 6.6 | 9.3 | 3.8 | - | - | - |

| CCB | - | - | - | 9.3 | 16.1 | 7.2 | - | - | - | 4.6 | 6.3 | 2.8 | - | - | - |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CAC, coronary artery calcium; CCB, calcium channel blockers; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; L-L, lipid-lowering; LDL, low-density lipoprotein. Values are expressed as rates (%) or mean±standard deviation.

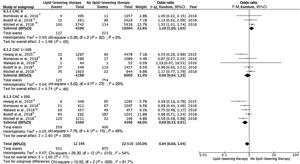

Forest plots for the risk of ASCVD occurrence with vs without lipid-lowering therapy in the overall population and stratified by CAC categories are reported in figure 2. In the overall primary prevention population, numerically reduced ASCVD events were observed among patients on lipid-lowering therapy (hazard ratio, 0.84; 95%CI, 0.68-1.04, I2=54%), a difference that became statistically significant when only adjusted data were pooled (hazard ratio, 0.59; 95%CI, 0.38-0.91, I2=85%), figure 3). A significant interaction was observed among CAC subgroups (P=.004, figure 2), so that lipid-lowering therapy was associated with reduced occurrence of ASCVD in patients with CAC> 100 (odds ratio [OR], 0.69; 95%CI, 0.53-0.91, I2=48%), but not in patients with CAC 1-100 or CAC 0. Results were consistent when adjusted data-only were pooled (figure 3). An assessment of the plausibility of the observed subgroup differences18 is detailed in the .

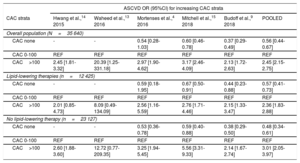

ASCVD incidence rates for each study are reported in . A graded increase in ASCVD occurrence was observed for increasing CAC strata (table 3). Compared with patients with CAC 1-100, patients with CAC 0 were at lower (OR, 0.56; 95%CI, 0.44-0.67), and patients with CAC> 100 were at higher (OR, 2.45; 95%CI, 2.15-2.75) risk of ASCVD. The results were consistent both in patients with and without lipid-lowering therapy (table 3) and remained similar in a sensitivity analysis limited to patients on lipid-lowering therapy prior to CAC assessment ().

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for ASCVD occurrence categorized by CAC strata

| ASCVD OR (95%CI) for increasing CAC strata | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC strata | Hwang et al.,14 2015 | Waheed et al.,13 2016 | Mortenses et al.,4 2016 | Mitchell et al.,15 2018 | Budoff et al.,9 2018 | POOLED |

| Overall population (N=35 640) | ||||||

| CAC none | - | - | 0.54 [0.28-1.03] | 0.60 [0.46-0.78] | 0.37 [0.29-0.49] | 0.56 [0.44-0.67] |

| CAC 0-100 | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| CAC>100 | 2.45 [1.81-3.32] | 20.39 [1.25-331.18] | 2.97 [1.90-4.62] | 3.17 [2.46-4.09] | 2.13 [1.72-2.63] | 2.45 [2.15-2.75] |

| Lipid-lowering therapies (n=12 425) | ||||||

| CAC none | - | - | 0.59 [0.18-1.95] | 0.67 [0.50-0.91] | 0.44 [0.23-0.88] | 0.57 [0.41-0.73] |

| CAC 0-100 | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| CAC>100 | 2.01 [0.85-4.73] | 8.09 [0.49-134.09] | 2.56 [1.16-5.59] | 2.76 [1.71-4.46] | 2.15 [1.33-3.47] | 2.36 [1.83-2.88] |

| No lipid-lowering therapy (n=23 127) | ||||||

| CAC none | - | - | 0.53 [0.36-0.78] | 0.59 [0.40-0.88] | 0.38 [0.29-0.50] | 0.48 [0.34-0.61] |

| CAC 0-100 | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| CAC>100 | 2.60 [1.88-3.60] | 12.72 [0.77-209.35] | 3.25 [1.94-5.45] | 5.56 [3.31-9.33] | 2.14 [1.67-2.74] | 3.01 [2.05-3.97] |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CAC, coronary artery calcium; OR, odds ratio; REF, reference.

The main findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the interaction between lipid-lowering therapy and CAC score in relation to ASCVD occurrence among asymptomatic individuals are as follows:

- •

A CAC score> 100 identified patients most likely to benefit from lipid-lowering therapy, while no such association was observed among patients with CAC ≤ 100 or no detectable CAC.

- •

The CAC score effectively stratified ASCVD occurrence, with preserved risk stratification ability among patients on lipid-lowering therapy.

No prospective evidence is currently available to support the impact of a CAC stratification-based strategy to guide lipid-lowering therapy on ASCVD outcomes among asymptomatic individuals. The single RCT available to date randomizing patients to lipid-lowering therapy vs placebo following CAC score assessment showed a nonsignificant trend of ASCVD event reduction, reaching significance only among patients with CAC> 400 (post hoc analysis).17 However, the study was limited by its small sample size and low event rate, along with high crossover and dropout rates.

On these bases, recommendations by the European Society of Cardiology regarding CAC use to drive lipid-lowering therapy remain weak and a statement was made on the need to further investigate the incremental value of reclassifying total cardiovascular risk and defining eligibility for lipid-lowering therapy based on CAC score.11

Although similar statements have been issued for years, RCTs of CAC-guided prevention powered for hard endpoints have not been carried out, likely due to anticipated trial size, costs, and ethical concerns about withdrawing lipid-lowering therapy among patients with high CAC score.19

We therefore performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of CAC studies reporting CAC-stratified ASCVD outcomes in patients with and without lipid-lowering therapy to gain insight on this issue.

Our study results are consistent with previous CAC literature showing a graded increase in ASCVD events across growing CAC strata and further expands this concept by suggesting an interaction of CAC with the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy.

Indeed, CAC score identifies the presence and extent of subclinical coronary atherosclerotic disease (which is the substratum for ASCVD events) rather than its probability, as is the case for clinical risk scores. The clinical implications of this concept are supported by a wealth of evidence highlighting a disconnect between the clinical risk profile and the atherosclerotic burden of asymptomatic individuals, with significant risk reclassification abilities of CAC over traditional risk estimators.

Individuals with no detectable coronary artery calcium scoreAmong individuals with no detectable CAC, representing 41% to 57% of individuals eligible for lipid-lowering therapy, the 10-year actual ASCVD event rate was much lower than predicted, ranging between 1.5% and 4.9%.20 Similarly, among individuals with ≥ 3 risk factors, 35% had no detectable CAC and a 7-year ASCVD event rate of around 3/1000 person-years.21

Our results, not accounting for the clinical risk profile, consistently suggest that lipid-lowering in this population therapy may not be beneficial. Caution is warranted in translating this finding to specific subsets, including smokers, individuals with severe familial hypercholesterolemia, those with a strong family history of ASCVD and those with a 10-year ASCVD estimated risk ≥ 20%, who demonstrated substantial 10-year actual ASCVD risk despite no detectable CAC.11,20,22,23

Regarding young individuals (<45 years), no detectable CAC is highly prevalent (consistently more than 90% across the literature); accordingly its role as a screening strategy in this subset has been questioned.7 When available, a CAC 0 entails a very benign prognosis with an estimated 10-year mortality of 0.4%.21 Nevertheless, considering the very long-term expected lifespan of this population and that ASCVD event risk depends on cumulative prior exposure to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol,24 it remains to be established whether early initiation of lipid-lowering therapy may translate into a very long-term clinical benefit in young hypercholesterolemic individuals.

Individuals with coronary artery calcium score 1-100We found no significant treatment benefit among patients with CAC 1-100, including in the analysis adjusted for clinical risk factors (aOR, 0.64; 95%CI, 0.36-1.13; P=.12, I2=74%). However, the numerical trend toward a benefit of lipid-lowering therapy (against a background of previous studies showing that 10% ASCVD actual risk in patients with CAC 1-100 varies widely between 3.8% and 14.3% according to sex, age and ethnicity9) suggests that, in this CAC range, ASCVD clinical risk estimation is warranted to indicate lipid-lowering therapy. This concept has been empirically embraced by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines, which favor lipid-lowering therapy initiation only in adults> 55 years of age, when CAC scores of 1 to 99 are found.23

Individuals with coronary artery calcium score> 100A CAC score> 100 identifies individuals at the higher end of the cardiovascular risk spectrum despite a low burden of traditional risk factors. Specifically, it translates into an 10-year actual risk of ASCVD> 7.5%, regardless of clinically estimated 10-year ASCVD risk.9 Young individuals (< 45 years) with elevated CAC burden had a much higher mortality risk than elderly individuals (> 75 years) with a CAC score of zero.25 Similarly, among individuals with no risk factors, 12% had CAC> 100 and experienced an ASCVD rate of 9.2 per 1000 person-years.21

Our study findings extend these observations further by showing a substantial benefit of lipid-lowering therapy in patients with CAC> 100. A Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force assessing the benefits and harms of CAC score suggested that the score may inappropriately reclassify individuals not having ASCVD into higher-risk categories, thus prompting unneeded treatment.26 Our analysis does not concur with this concept, since a consistent treatment benefit was observed among these patients and in the analysis adjusted by clinical risk factors.

Of note, the utility of a CAC-guided over clinically-guided treatment strategy in primary prevention seems to apply also to aspirin, for which recent studies adopting meta-analysis data on ASCVD relative risk reduction and bleeding risk seem to suggest that, while aspirin allocation guided by the pooled cohort equations may translate in net harm across all ASCVD risk classes, a strategy complemented by CAC evaluation may identify subsets of patients with a risk trade-off favoring aspirin treatment (ie, patients with CAC> 100 in the setting of low bleeding risk and more than low ASCVD risk).27,28

Finally, CAC-guided compared with clinical risk-guided lipid-lowering therapy appears to have a cost-effective profile.29 The single RCT comparing a CAC-based with a risk factor-based strategy consistently showed improved cardiovascular risk factor control without increased downstream resource use by more appropriate resource allocation to at risk patients.30

To conclude, we observed that the CAC stratification ability was preserved among patients on lipid-lowering therapies, both among those already on treatment at CAC assessment and among those starting treatment thereafter.

Some authors have raised concerns that the plaque-stabilizing effect of statins, which is reflected by an increase in CAC score, might affect the risk stratification ability of CAC score assessment among patients on lipid-lowering therapies.30,31 As a consequence, European Society of Cardiology guidelines warrant caution when interpreting CAC score values among patients on lipid-lowering therapy.11 Our finding is reassuring, by showing that the prognostic implications of CAC score remain valid among patients already on lipid-lowering treatment. This observation is consistent with a recent analysis from the CAC consortium, which showed that CAC retains robust risk prediction in statin users, though with a slightly weaker power compared with a statin nonuser, likely explained by the changing relationship of CAC density among statin users.32

LimitationsThe findings of this meta-analysis should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, this is a study-level meta-analysis, and the findings provide mean study-level effects. Second, the rate of crossovers and the variable exposures to lipid-lowering drugs in the studies included in the analysis may complicate the interpretation of the results. Third, we report both unadjusted and adjusted pooled effect estimates, as the latter were available for only 2 studies (and 1 study for the CAC 0 group). Moreover, despite adjustment, this analysis cannot account for unmeasured covariates and do not completely eliminate confounding bias. However, the consistency between the results of the analyses support the validity of our observations. Fourth, ASCVD definition varied among studies. Even though the effect size of benefit of lipid-lowering therapy was similar among individual cardiovascular outcomes (with slight attenuation for stroke and cardiovascular death, compared with myocardial infarction and coronary revascularization)1, the reported relative effect estimates should be interpreted in this context.

CONCLUSIONSAmong individuals without a previous ASCVD, there is an association between increasing CAC strata and the expected benefit from lipid-lowering therapy. A CAC score> 100 identifies individuals most likely to benefit from lipid-lowering therapy, while undetectable CAC suggests no treatment benefit. These findings may stimulate discussion toward a paradigm shift in risk assessment with a focus on the detection of subclinical atherosclerosis rather than the probability of disease presence.

- -

CAC score improves the accuracy of risk stratification for ASCVD events compared with traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

- -

In the setting of primary prevention, a CAC score> 100 identifies persons most likely to benefit from lipid-lowering therapy, while undetectable CAC suggests no treatment benefit. A paradigm shift in risk assessment with a focus on subclinical atherosclerosis detection rather than disease probability requires exploration.

No funding was required for this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSG. Gallone, E. Elia, F. Bruno, L. Baldetti, F. D’Ascenzo, A. Esposito, A. Depaoli, P. Fonio, and G.M. De Ferrari were involved in the conception and design of the study. G. Gallone, E. Elia, F. Angelini, L. Franchin, P.P. Bocchino, F. Piroli, U. Annone, A. Serafini, A. Montabone, M. Beratina, O. De Filippo, A. Palmisano, and G. Marengo performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of data, critically revised the manuscript, approved it in its current form, and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2021.08.002