On November 11, 2020, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) had infected 9 187 237 people worldwide with an estimated mortality rate of 2.7%.1 Initial reports hinted that a dysregulated immune system might play a key role in its lethality.2 Patients with a prior history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or risk factors are particularly at higher risk.3

Statins are common among high-risk patients and have been demonstrated to diminish the incidence of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Interestingly, it has previously been suggested that statins may confer a protective benefit in viral infections. In theory, statins might lessen the incidence of acute injury in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by: a) decreasing L-mevalonate downstream mediators; b) through inhibition of protein prenylation; and c) upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 levels.4 However, the greater use of statins in patients with a higher CVD burden might counterbalance a potential protective effect compared with nonstatin users. Our aim was to describe the characteristics and evaluate the impact of chronic statin treatment in the prognosis of patients admitted to hospital due to COVID-19.

We have performed a retrospective, observational study performed in 2 Spanish tertiary hospitals of all admitted patients between March 1 and April 30, 2020 with a definitive diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed through positive reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. We recorded prescribed therapy before admission and during hospital stay according to the protocols of our institutions and the discretion of the medical team. Clinical outcomes were also registered. Categorical variables are reported as absolute values and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation; non normally distributed variables are reported as median [interquartile range]. The effect of statins on the primary outcome (in-hospital mortality) in the overall study population was evaluated with a multivariate logistic regression model after adjustment for the main cofounding factors. All the analyses were conducted using the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0. (IBM Corp, United States). Differences were considered statistically significant when P was <.05. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and informed consent was waived given its retrospective and observational nature.

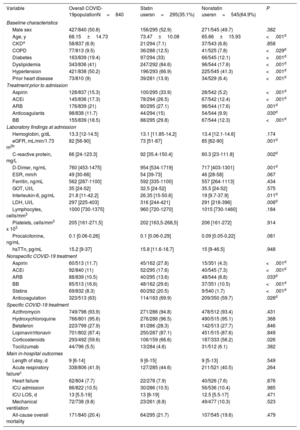

Out of 840 patients admitted due to COVID-19, 295 (35.1%) were under statin therapy before hospital admission and 545 (64.9%) were not. Patients treated with statins were older (73.5±10.1 vs 65.7±15.9; P <.001) and had a higher prevalence of several comorbidities including hypertension (66.9% vs 41.3%; P <.001), diabetes mellitus (33% vs 12.1%; P <.001), and prior heart disease (13.9% vs 6.4%; P <.001). In parallel, those under statin therapy were more often receiving antihypertensive drugs, beta-blockers, and aspirin. Time from symptom onset to admission did not differ between groups. Statin users had a more prominent inflammatory profile at admission with higher C-reactive protein (92 vs 60.3mg/dL; P=.002), interleukin-6 (26.35 vs 19 pg/mL; P=.011), and D-dimer levels (954 vs 717; P=.001). Overall, patients in the statin cohort were more commonly treated with intravenous corticosteroids (66.7% vs 56.2%; P <.026) and anticoagulants (69.9% vs 59.7%; P=.033), but other empirical drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 were used in similar rates. Major in-hospital outcomes including acute respiratory failure (9.8%), intensive care admission (10.5%), and all-cause mortality (20.4%) were comparable. Main baseline characteristics according to lipid-lowering treatment at baseline are summarized in table 1.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of statin vs nonstatin users infected with SARS-CoV-2

| Variable | Overall COVID-19populationN=840 | Statin usersn=295(35.1%) | Nonstatin usersn=545(64.9%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Male sex | 427/840 (50.8) | 156/295 (52.9) | 271/545 (49.7) | .382 |

| Age, y | 68.15±14.73 | 73.47±10.08 | 65.66±15.93 | <.001d |

| CKDa | 58/837 (6.9) | 21/294 (7.1) | 37/543 (6.8) | .858 |

| COPD | 77/813 (9.5) | 36/288 (12.5) | 41/525 (7.8) | <.029d |

| Diabetes | 163/839 (19.4) | 97/294 (33) | 66/545 (12.1) | <.001d |

| Dyslipidemia | 343/836 (41) | 247/292 (84.6) | 96/544 (17.6) | <.001d |

| Hypertension | 421/838 (50.2) | 196/293 (66.9) | 225/545 (41.3) | <.001d |

| Prior heart disease | 73/810 (9) | 39/281 (13.9) | 34/529 (6.4) | <.001d |

| Treatment prior to admission | ||||

| Aspirin | 128/837 (15.3) | 100/295 (33.9) | 28/542 (5.2) | <.001d |

| ACEi | 145/836 (17.3) | 78/294 (26.5) | 67/542 (12.4) | <.001d |

| ARB | 176/839 (21) | 80/295 (27.1) | 96/544 (17.6) | .001d |

| Anticoagulants | 98/838 (11.7) | 44/294 (15) | 54/544 (9.9) | .030d |

| BB | 155/839 (18.5) | 88/295 (29.8) | 67/544 (12.3) | <.001d |

| Laboratory findings at admission | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.3 [12-14.5] | 13.1 [11.85-14.2] | 13.4 [12.1-14.6] | .174 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2b | 82 [56-90] | 73 [51-87] | 85 [62-90] | .001d |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 66 [24-123.3] | 92 [35.4-150.4] | 60.3 [23-111.8] | .002d |

| D-Dimer, ng/mL | 760 [453-1475] | 954 [534-1719] | 717 [403-1301] | .001d |

| ESR, mm/h | 49 [30-66] | 54 [39-73] | 46 [28-58] | .067 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 562 [287-1100] | 592 [335-1100] | 557 [264-1113] | .434 |

| GOT, UI/L | 35 [24-52] | 32.5 [24-52] | 35.5 [24-52] | .575 |

| Interleukin-6, pg/mL | 21.8 [11-42.2] | 26.35 [15-50.6] | 19 [9.7-37.9] | .011d |

| LDH, UI/L | 297 [225-403] | 316 [244-421] | 291 [218-396] | .006d |

| Lymphocytes, cells/mm3 | 1000 [730-1375] | 960 [720-1270] | 1015 [730-1460] | .184 |

| Platelets, cells/mm3 x 103 | 205 [161-271,5] | 202 [163,5-268,5] | 206 [161-272] | .914 |

| Procalcitonine, ng/mL | 0.1 [0.06-0.26] | 0.1 [0.06-0.29] | 0.09 [0.05-0.22] | .081 |

| hsTTn, pg/mL | 15.2 [9-37] | 15.8 [11.6-18.7] | 15 [9-46.5] | .948 |

| Nonspecific COVID-19 treatment | ||||

| Aspirin | 60/513 (11.7) | 45/162 (27.8) | 15/351 (4.3) | <.001d |

| ACEi | 92/840 (11) | 52/295 (17.6) | 40/545 (7.3) | <.001d |

| ARB | 88/839 (10.5) | 40/295 (13.6) | 48/544 (8.8) | .033d |

| BB | 85/513 (16.6) | 48/162 (29.6) | 37/351 (10.5) | <.001d |

| Statins | 69/832 (8.3) | 60/292 (20.5) | 9/540 (1.7) | <.001d |

| Anticoagulation | 323/513 (63) | 114/163 (69.9) | 209/350 (59.7) | .026d |

| Specific COVID-19 treatment | ||||

| Azithromycin | 749/798 (93.9) | 271/286 (94.8) | 478/512 (93.4) | .431 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 766/801 (95.6) | 276/286 (96.5) | 490/515 (95.1) | .368 |

| Betaferon | 223/799 (27.9) | 81/286 (28.3) | 142/513 (27.7) | .846 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 701/802 (87.4) | 250/287 (87.1) | 451/515 (87.6) | .849 |

| Corticosteroids | 293/492 (59.6) | 106/159 (66.6) | 187/333 (56.2) | .026 |

| Tocilizumab | 44/796 (5.5) | 13/284 (4.6) | 31/512 (6.1) | .382 |

| Main in-hospital outcomes | ||||

| Length of stay, d | 9 [6-14] | 9 [6-15] | 9 [5-13] | .549 |

| Acute respiratory failurec | 338/806 (41.9) | 127/285 (44.6) | 211/521 (40.5) | .264 |

| Heart failure | 62/804 (7.7) | 22/278 (7.9) | 40/526 (7.6) | .876 |

| ICU admission | 86/822 (10.5) | 30/286 (10.5) | 56/536 (10.4) | .985 |

| ICU LOS, d | 13 [5.5-19] | 13 [8-19] | 12.5 [5.5-17] | .471 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 72/738 (9.8) | 23/261 (8.8) | 49/477 (10.3) | .523 |

| All-cause overall mortality | 171/840 (20.4) | 64/295 (21.7) | 107/545 (19.6) | .479 |

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta-blockers; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; hsTTn, high-sensitivity T-troponin.

Values are expressed as mean±standard deviation, median [interquartile range], or No. (%).

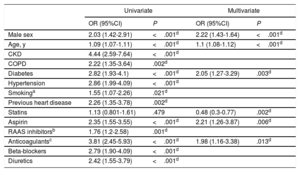

A logistic regression model was used to study the association between chronic statin use with clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The following variables were included in the definitive model: age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, history of cigarette smoking, prior heart disease, and chronic adjuvant therapies (renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, beta-blockers, aspirin, and anticoagulation). In this model (see table 2), chronic statin treatment (adjusted odds ratio of 0.48, 95% confidence interval, 0.3-0.77; P=.002) was associated with lower in-hospital mortality compared with nonstatin users. In addition, elderly patients, male patients and diabetic patients were at a higher risk of death due to COVID-19.

Predictors of 30-day mortality in the study population

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Male sex | 2.03 (1.42-2.91) | <.001d | 2.22 (1.43-1.64) | <.001d |

| Age, y | 1.09 (1.07-1.11) | <.001d | 1.1 (1.08-1.12) | <.001d |

| CKD | 4.44 (2.59-7.64) | <.001d | ||

| COPD | 2.22 (1.35-3.64) | .002d | ||

| Diabetes | 2.82 (1.93-4.1) | <.001d | 2.05 (1.27-3.29) | .003d |

| Hypertension | 2.86 (1.99-4.09) | <.001d | ||

| Smokinga | 1.55 (1.07-2.26) | .021d | ||

| Previous heart disease | 2.26 (1.35-3.78) | .002d | ||

| Statins | 1.13 (0.801-1.61) | .479 | 0.48 (0.3-0.77) | .002d |

| Aspirin | 2.35 (1.55-3.55) | <.001d | 2.21 (1.26-3.87) | .006d |

| RAAS inhibitorsb | 1.76 (1.2-2.58) | .001d | ||

| Anticoagulantsc | 3.81 (2.45-5.93) | <.001d | 1.98 (1.16-3.38) | .013d |

| Beta-blockers | 2.79 (1.90-4.09) | <.001d | ||

| Diuretics | 2.42 (1.55-3.79) | <.001d | ||

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OR, odds ratio; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors.

Statins, with their pleiotropic properties, have the potential to reduce the severity of acute lung injury and mortality. Our findings are in agreement with those of a recent retrospective study that evaluated the impact of chronic statin treatment prior to COVID-19 hospitalization, in which statin use before hospital admission was associated with a 71% reduction for developing severe COVID-19.5 Likewise, Xiao-Jing Zhang et al.6 observed that in-hospital statin use was also associated with improved outcomes among COVID-19 patients.

This study has several limitations. Given the study design, we cannot infer causality of statins on mortality and it should be considered hypothesis generating. Our findings may be limited by the fact that we did not evaluate patients not admitted to hospital or under the effect of some unmeasured in-hospital confounders (eg, statin maintenance and impact of concomitant treatments). However, our results suggest that statin users with COVID-19 have a greater baseline risk mainly driven by more advanced age and a high burden of cardiovascular comorbidities, which might in theory disguise a potential protective effect of statins in this particular subset of patients. There is currently no evidence from any randomized controlled trial to show whether in-hospital statins may benefit patients with COVID-19, but we would like to draw the attention of the international community to this possibility until conclusive evidence is reported (STATCO19, NCT04380402).

FundingThis work was partially funded by the Gerencia Regional de Salud de Castilla y León (GRS COVID 111/A/20) and the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC/FEC-INVCLI 20/030).

Conflicts of interestNone conflicts of interest.