Until 3 to 4 decades ago, infective endocarditis (IE) was considered to be a subacute disease caused by cardiac lesions infected by oral flora microorganisms (mainly Streptococcus viridans). This type of IE has a relatively good prognosis, bearing in mind the severity of this disease.1 However, the clinical and epidemiological profile and prognosis of IE have changed under the impact of recent social and health care changes, such as aging populations, increased numbers of other causal microorganisms (mainly staphylococci and enterococci), and new risk factors (eg, injectable drug use, prosthetic valves, electrical devices, or health care-related bacteremia).2–6 The aim of this study was to analyze the characteristics of oral streptococci IE in a Spanish tertiary hospital, as well as changes in its relative incidence, treatment, and prognosis using a large single-center series collected over the last 30 years in this setting.

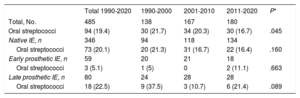

We analyzed a cohort of consecutive patients diagnosed with IE and followed up in our hospital between 1990 and 2020 (n=485) to identify cases of IE caused by oral streptococci (S. viridans and nutritionally variant streptococci: Abiotrophia and Granulicatella) and to compare their characteristics during 3 time periods (1990-2000, 2001-2010, and 2011-2020). The study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital and informed consent was given by all the participants. Of the 485 cases of IE, 346 were native, 59 were early prosthetic, and 80 were late prosthetic. In total, 19.4% (n=94) of the 485 cases were caused by oral streptococci (90 S. viridans, 3 Abiotrophia, and 1 Granulicatella). The most frequent causative organisms were staphylococci (37.9%), followed by enterococci (16.3%). Table 1 shows the number of patients with IE caused by oral streptococci during the 3 time periods and by the various types of IE. Oral streptococci caused 20.1% of native IE and 22.5% of late prosthetic IE, but were very rare in early prosthetic IE. A significant reduction was observed in the proportion of cases caused by these microorganisms, decreasing from 21.7% in the period 1990 to 2000 to 16.7% in the period 2011 to 2020 (P=.045) (table 1). Similar trends were seen regarding native and late prosthetic IE, although without reaching significance (table 1).

Number of cases and percentage of endocarditis due to oral streptococci in the total series and by the various types of infective endocarditis during the 3 time periods analyzed

| Total 1990-2020 | 1990-2000 | 2001-2010 | 2011-2020 | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, No. | 485 | 138 | 167 | 180 | |

| Oral streptococci | 94 (19.4) | 30 (21.7) | 34 (20.3) | 30 (16.7) | .045 |

| Native IE, n | 346 | 94 | 118 | 134 | |

| Oral streptococci | 73 (20.1) | 20 (21.3) | 31 (16.7) | 22 (16.4) | .160 |

| Early prosthetic IE, n | 59 | 20 | 21 | 18 | |

| Oral streptococci | 3 (5.1) | 1 (5) | 0 | 2 (11.1) | .663 |

| Late prosthetic IE, n | 80 | 24 | 28 | 28 | |

| Oral streptococci | 18 (22.5) | 9 (37.5) | 3 (10.7) | 6 (21.4) | .089 |

IE, infective endocarditis.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as No. (%).

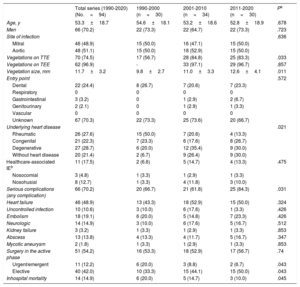

Table 2 shows the characteristics of oral streptococcal IE by each time period: no significant differences were observed in age, sex, entry point for bacteremia, most frequent comorbidities, endocarditis site, or relationship with health care. Significant changes were detected over time in the etiology of the underlying heart disease (P=.021), with a reduction in rheumatic etiology and an increase in degenerative etiology and the absence of underlying heart disease. Vegetation size was larger during the more recent periods, although this was probably not due to greater streptococcal aggressiveness, given that the incidence of cardiac complications, persistence of infection, neurologic complications, kidney failure, embolisms, abscesses, and mycotic aneurysms were similar over the study period. All complications involved clinical symptoms, because in our protocol we did not conduct a systematic search for neurologic complications, embolisms, mycotic aneurysms, and so on, in the absence of symptoms or clinical suspicion. Of the 13 abscesses, 12 were periannular and only 1 was distant (splenic). Overall, the incidence of all serious complications, which was 70.2% during the entire period from 1990 to 2020, significantly increased between the periods 1990 to 2000 and 2011 to 2020 (P=.031). The rate of early surgery was similar during the 3 periods (more than 50%), although we observed a decrease in urgent/emergent surgery and a gradual increase in indications for elective surgery (P=.04).

Comparison of the characteristics of infective endocarditis caused by oral streptococci in the overall series and in the 3 time periods studied

| Total series (1990-2020) (No.=94) | 1990-2000 (n=30) | 2001-2010 (n=34) | 2011-2020 (n=30) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 53.3±18.7 | 54.6±18.1 | 53.2±18.6 | 52.8±18.9 | .678 |

| Men | 66 (70.2) | 22 (73.3) | 22 (64.7) | 22 (73.3) | .723 |

| Site of infection | .636 | ||||

| Mitral | 46 (48.9) | 15 (50.0) | 16 (47.1) | 15 (50.0) | |

| Aortic | 48 (51.1) | 15 (50.0) | 18 (52.9) | 15 (50.0) | |

| Vegetations on TTE | 70 (74.5) | 17 (56.7) | 28 (84.8) | 25 (83.3) | .033 |

| Vegetations on TEE | 62 (96.9) | - | 33 (97.1) | 29 (96.7) | .857 |

| Vegetation size, mm | 11.7±3.2 | 9.8±2.7 | 11.0±3.3 | 12.6±4.1 | .011 |

| Entry point | .572 | ||||

| Dental | 22 (24.4) | 8 (26.7) | 7 (20.6) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Respiratory | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (3.2) | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Genitourinary | 2 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Vascular | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 67 (70.3) | 22 (73.3) | 25 (73.6) | 20 (66.7) | |

| Underlying heart disease | .021 | ||||

| Rheumatic | 26 (27.6) | 15 (50.0) | 7 (20.6) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Congenital | 21 (22.3) | 7 (23.3) | 6 (17.6) | 8 (26.7) | |

| Degenerative | 27 (28.7) | 6 (20.0) | 12 (35.4) | 9 (30.0) | |

| Without heart disease | 20 (21.4) | 2 (6.7) | 9 (26.4) | 9 (30.0) | |

| Healthcare-associated IEb | 11 (17.5) | 2 (6.6) | 5 (14.7) | 4 (13.3) | .475 |

| Nosocomial | 3 (4.8) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Nosohusial | 8 (12.7) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (11.8) | 3 (10.0) | |

| Serious complications (any complication) | 66 (70.2) | 20 (66.7) | 21 (61.8) | 25 (84.3) | .031 |

| Heart failure | 46 (48.9) | 13 (43.3) | 18 (52.9) | 15 (50.0) | .324 |

| Uncontrolled infection | 10 (10.6) | 3 (10.0) | 6 (17.6) | 1 (3.3) | .426 |

| Embolism | 18 (19.1) | 6 (20.0) | 5 (14.8) | 7 (23.3) | .426 |

| Neurologic | 14 (14.9) | 3 (10.0) | 6 (17.6) | 5 (16.7) | .512 |

| Kidney failure | 3 (3.2) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (3.3) | .853 |

| Abscess | 13 (13.8) | 4 (13.3) | 4 (11.7) | 5 (16.7) | .347 |

| Mycotic aneurysm | 2 (1.8) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (3.3) | .853 |

| Surgery in the active phase | 51 (54.2) | 16 (53.3) | 18 (52.9) | 17 (56.7) | .74 |

| Urgent/emergent | 11 (12.2) | 6 (20.0) | 3 (8.8) | 2 (6.7) | .043 |

| Elective | 40 (42.0) | 10 (33.3) | 15 (44.1) | 15 (50.0) | .043 |

| Inhospital mortality | 14 (14.9) | 6 (20.0) | 5 (14.7) | 3 (10.0) | .045 |

IE, infective endocarditis; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Early mortality due to oral streptococcal IE significantly decreased from 16.7% in the period 1990 to 2000 to 10% in the period 2011 to 2020 (table 2), despite the increased incidence of severe complications already discussed. This inconsistency may be partly due to the higher rate of elective surgery, which prevents poor disease progression. The results of the multivariable study (stepwise logistic regression) showed an association between streptococcal etiology and a significant reduction in mortality of 26% in the total series (odds ratio=0.74; 95% confidence interval: 0.56-0.92; P=.043).

In conclusion, our analysis of a large single-center series of IE spanning a long time period showed that oral streptococci, mainly S. viridans, continued to cause around 20% of all IE, especially native and late prosthetic endocarditis. Nevertheless, their relative incidence seems to have decreased in recent years, probably due to the increase in cases caused by other microorganisms, such as staphylococci and enterococci. Over the 3 decades analyzed, the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of IE, the incidence of serious complications, and the performance of early surgery have remained unchanged, although in-hospital mortality has recently decreased, reaching just 10% in the last decade.

FUNDINGNone declared.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll authors contributed equally to the concept, design, data analysis, writing, and revision of the article.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.