To study the impact of injecting intracoronary eptifibatide plus vasodilators via thrombus aspiration catheter vs thrombus aspiration alone in reducing the risk of no-reflow in acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) with diabetes and high thrombus burden.

MethodsThe study involved 413 diabetic STEMI patients with high thrombus burden, randomized to intracoronary injection (distal to the occlusion) of eptifibatide, nitroglycerin and verapamil after thrombus aspiration and prior to balloon inflation (n=206) vs thrombus aspiration alone (n=207). The primary endpoint was post procedural myocardial blush grade and corrected Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) frame count (cTFC). Major adverse cardiovascular events were reported at 6 months.

ResultsThe intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators arm was superior to thrombus aspiration alone regarding myocardial blush grade-3 (82.1% vs 31.4%; P=.001). The local intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators arm had shorter cTFC (18.16±6.54 vs 29.64±5.53, P=.001), and better TIMI 3 flow (91.3% vs 61.65%; P=.001). Intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators improved ejection fraction at 6 months (55.2±8.13 vs 43±6.67; P=.005). There was no difference in the rates of major adverse cardiovascular events at 6 months.

ConclusionsAmong diabetic patients with STEMI and high thrombus burden, intracoronary eptifibatide plus vasodilators injection was beneficial in preventing no-reflow compared with thrombus aspiration alone. Larger studies are encouraged to investigate the benefit of this strategy in reducing the risk of adverse clinical events.

Keywords

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the gold standard management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)1. However, no-reflow is not uncommon and is associated with increased mortality.2–4 Pharmacological therapies such as vasodilators and antiplatelet agents as well as aspiration thrombectomy have shown benefit in the treatment and reduction of the risk of the no-reflow phenomenon.5–9 Intracoronary glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors (GPI) is associated with additional benefits compared with intravenous bolus application.10 But on the downside, it does not allow an optimal contact between the plaque components and the drug, which is rapidly washed out by the coronary flow. An advantage to local administration of the drug at the culprit site is that this route provides up a much higher drug concentration, compared with intravenous drug delivery.11–13

Although local vasodilator therapy and local antiplatelet therapy are widely used to manage the no-reflow phenomenon, only local vasodilator therapy has a specific guideline indication for treatment of no-reflow. The 2011 American College of Cardiology revascularization guidelines14 provides a class IIa recommendation for administration of an intracoronary vasodilator (specifically, adenosine, calcium channel blocker, or nitroprusside) to treat PCI-related no-reflow that occurs during primary or elective PCI.

Thrombus-aspiration-assisted primary intervention help to achieve complete ST-segment resolution in some patients.15 Although routine aspiration thrombectomy is not recommended for the management of STEMI,1 it might be considered in cases with high thrombus burden. As diabetic patients are more prone to no-reflow and higher thrombus grades,3,5 we investigated the benefit of GPI with vasodilators distal to the lesion via thrombus aspiration after thrombectomy among diabetic patients with STEMI and high thrombus burden.

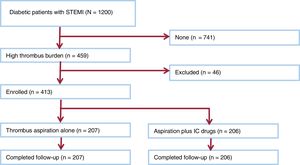

METHODSStudy design and patient selectionIn this study, we randomized 413 diabetic patients with STEMI who presented within 12 hours of symptoms onset and underwent primary PCI between December 2016 and May 2019 in 5 different centers. We enrolled patients during this specified recruitment period, thus a sample size calculation was not performed. Patients were randomly assigned to either group using a block randomization. Diabetes was diagnosed, by history and/or according to American Diabetes Association, based on a fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, a random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL plus associated symptoms of hyperglycemia or a HbA1c level ≥ 6.5%.16

The exclusion criteria included: use of a fibrinolytic agent within 14 days before PCI, suspected active internal bleeding, history of cerebrovascular accident within the previous 2 years or known platelet count <100 000 cells/μl, TIMI flow grade ≥ 2 or thrombus grade ≤ 2 and cardiogenic shock.

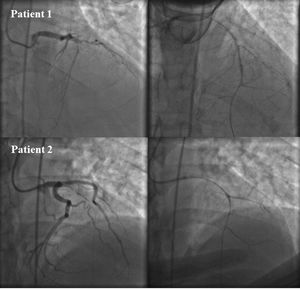

Before PCI, only patients with large angiographic thrombus burden (grade ≥ 3) and planned for aspiration thrombectomy to reduce the thrombus burden according to the operator's discretion were eligible for enrollment. Patients were randomized to either thrombus aspiration alone (using Export Aspiration Catheter; Medtronic, United States) (n=207) or to receive local delivery of 180 μg/kg intracoronary eptifibatide plus 100 μg verapamil and 100 μg nitroglycerin given via thrombus aspiration with ≤ 5cc contrast to visualize the distal bed (n=206). After aspiration, the thrombectomy catheter was removed from the vessel, flushed with heparinized saline and subsequently re-introduced into the culprit vessel distal to the occlusion, prior to the selective administration of intracoronary drugs. The drugs were infused into the infarct-related artery after visualization of the distal bed with minimal amount of contrast following aspiration (figure 1). Conversely, balloon predilatation was permitted if thrombus aspiration was ineffective according to operator decision. In case of multivessel involvement, the infarct-related artery was treated first, and complete revascularization was performed in another session during hospital stay.

All patients were treated with drug eluting stent of the culprit lesion. All patients received weight adjusted dose of heparin during the procedure, dual antiplatelet therapy; aspirin 300 mg orally on presentation, ticagrelor 180 mg or clopidogrel 600 mg loading dose before PCI followed by daily maintenance dose for 1 year after stent implantation.

Routine laboratory investigations were done for all patients including cardiac biomarkers; high sensitivity troponin on admission and 6 hours after, creatinine phosphokinase (CK), CK-MB levels every 6 hours till normalization, serum creatinine level, complete blood picture on admission and daily until discharge. Echocardiography was reviewed by experienced, blinded operators during the index hospitalization and at 6 months to assess left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) using Simpson's method.

Before inclusion, informed written consent was obtained from each patient and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional human research committee. Moreover, the protection of the privacy of the participants was ensured, as well as the confidentiality of the research data.

EndpointsThe primary endpoints were postprocedural assessment of myocardial blush grade (MBG), postprocedural TIMI flow, and corrected TIMI frame count (cTFC). The secondary endpoints were 6-month rates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE); defined as all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, or target vessel revascularization during routine clinic visit assessment or by scheduled phone calls. Left ventricular EF was re-assessed at the end of the follow-up when MACE was analyzed.

TIMI thrombus grading classification was used to evaluate thrombus burden. Patients were considered to have angiographically evident thrombus if TIMI thrombus grade ≥ 3. Both TIMI flow and MBG were graded on the coronary angiogram with duration of cine filming at least 3 cardiac cycles to make sure that the entire washout phase was included. MBG was assessed during the same phase of the cardiac cycle. MBG and other quantitative coronary angiography parameters were measured and analyzed off-line by an interventional cardiologist who was blinded of the treatment assignment.

Statistical analysisThe collected data were coded, tabulated, and statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software version 22.0 (2013, IBM Corp., United States). Inferential analyses were performed for quantitative variables, independent Student t-test in cases of 2 independent groups with normally distributed data. In qualitative data, inferential analyses for independent variables were done using chi-square test for differences between proportions and Fisher's exact test for variables with small expected numbers. Descriptive statistics was performed for quantitative data as means±standard deviation since the data were normally distributed data, while qualitative data were presented as number and percentage. The level of significance was set at P-value <.05 is significant, otherwise was considered nonsignificant.

RESULTSStudy populationDuring the study period, 413 patients who presented with acute STEMI, and planned for primary PCI were included in the study (figure 2). After angiographic confirmation of high thrombus burden, patients were randomized to either distal intracoronary injection of eptifibatide, verapamil and nitroglycerin through aspiration catheter after thrombus aspiration (n=206), or thrombus aspiration alone (n=207). The baseline demographic data, including age, sex and cardiovascular risk factors and infarct-related vessel is presented in table 1.

Baseline demographic data in the study groups

| Intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators | Thrombus aspiration alone | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 198 (95.6) | 195 (94.6) | .574 |

| Female sex | 9 (4.3) | 11 (5.3) | .476 |

| Age, y | 55.5±11.7 | 57.1±10.8 | .517 |

| Smoking | 142 (68.6) | 154 (74.7) | .689 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 113 (54.5) | 121 (58.7) | .980 |

| HTN | 68 (32.8) | 59 (28.6) | .790 |

| FH of premature CAD | 27 (13.0) | 31 (15.0) | .749 |

| CKD | 6 (2.9) | 8 (3.9) | .110 |

| PAD | 12 (5.8) | 9 (4.3) | .830 |

| Previous ACS | 14 (6.8) | 7 (3.4) | .749 |

| Prior PCI | 17 (8.2) | 22 (10.6) | .619 |

| Inotropes | 15 (7.3) | 18 (8.7) | .418 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.15±0.4 | 1.25±0.3 | .592 |

| Creatinine clearance | 73.8±22.9 | 67.5±20.2 | .417 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CKD, chronic kidney disease; FH, family history; HTN, hypertension; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention

The data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

In the intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators group, the peak CK-MB reached was 217.53±81.32, vs 364.17±157.12 in the thrombus aspiration alone group (P=.001). And the mean time to reach peak of CK-MB was 11.38±4.83 hours in the local intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators group, and 19.54±9.21hours in the thrombus aspiration alone group (P=.001).

There was no difference in the rates of ST resolution (mean value of 58.2%±13.91 in intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators group vs 52.7%±26.5 in the thrombus aspiration alone group, P=.40) (table 2).

Baseline angiographic and procedural parameters

| Intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators | Thrombus aspiration alone | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel related infarction | |||

| Left anterior descending artery | 102 (49.51) | 103 (49.75) | |

| Right coronary artery | 83 (40.29) | 76 (36.71) | .682 |

| Left circumflex artery | 21 (10.19) | 28 (13.52) | |

| Left main involvement | 3 (1.45) | 4 (1.93) | .829 |

| Multivessel disease | 39 (18.93) | 47 (22.7) | .733 |

| Stent length | 27.8±10.1 | 26.9±11.2 | .463 |

| Stent diameter | 3.04±0.4 | 3.13±0.3 | .761 |

| Pain to balloon, h | 8.6±7.3 | 9.4±7.7 | .618 |

| Door to balloon, min | 31±27.1 | 33±13.4 | .751 |

| Contrast amount, mL | 185.0±28.6 | 192.4±43.7 | .630 |

| ST resolution | 58.2±13.9 | 52.7±26.5 | .423 |

The data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Echo was performed on all patients before discharge, ejection fraction measured postinfarction was 46.9±6.36% in the intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators group vs 39.3±5.12% in the thrombus aspiration alone group, P=.005. Quantitative coronary angiography results are shown in table 3.

Results of quantitative coronary angiography

| Intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators | Thrombus aspiration alone | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal lumen diameter, mm | |||

| Before angioplasty | 0.5±0.4 | 0.6±0.3 | .75 |

| After angioplasty | 2.7±0.3 | 2.5±0.6 | .25 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | |||

| Before angioplasty | 83.3±9.5 | 81.2±10.5 | .79 |

| Angioplasty | 5.2±3.3 | 4.2±3.1 | .82 |

The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation.

There was a significant increase in number of patients with MBG 3 in the intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators group compared with the thrombus aspiration alone group was observed (80.5% vs 31.8% P=.001) and shorter cTFC (18.16±6.54 vs 29.64±5.53, P=.001). The intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators group had higher rates in achievement of TIMI 3 (91.3% vs 61.65%; P=.005). The rates of MACE were not statistically different between both groups (P> .05). One patient died in the intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators group during hospital stay, as well as in the thrombus aspiration alone group. Only one patient in thrombus aspiration alone group required revascularization in the infarct-related vessel after 2 months. There was no difference in the rates of procedure related complications, major or minor bleeding, or significant change in platelet count in both arms. EF was better at 6-month in the intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators (55.2±8.13 vs 43±6.67; P=.005) (table 4).

Procedural details and end points

| Intracoronary eptifibatide and vasodilators | Thrombus aspiration alone | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary end points | |||

| MBG3 | 82.1 | 31.4 | .001 |

| cTFC | 18.16±6.54 | 29.64±5.53 | .001 |

| TIMI3 | 91.3 | 61.65 | .005 |

| Secondary end points | |||

| MI | 0 | 0 | - |

| Mortality | 1 (0.48) | 1 (0.48) | 1.00 |

| Stroke | 1 (0.48) | 1 (0.48) | 1.00 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 0 | 1 (0.48) | 1.00 |

| Total MACE | 2 (0.96) | 3 (1.44) | .971 |

| EF (in-hospital) | 46.9±6.36 | 39.3±5.12 | .005 |

| EF (6-month) | 55.2±8.13 | 43±6.67 | .005 |

| Peak CK-MB level | 217.53±81.32 | 364.17±157.12 | .001 |

| Mechanical complication | 1 (0.48) | 0 | - |

| HF hospitalization | 1 (0.48) | 2 (0.96) | .182 |

| Minor bleeding | 3 (1.44) | 2 (0.96) | .212 |

| Major bleeding | 0 | 0 | - |

| CIN | 7 (3.39) | 5 (2.41) | .732 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 2 (0.96) | 1 (0.48) | .912 |

CIN, contrast induced nephropathy; EF, ejection fraction; HF, heart failure; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; MI, myocardial infarction.

The data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

The no-reflow phenomenon remains a challenging complication of acute myocardial infarction,17 with only few therapeutic interventions available. In this multicenter randomized trial including 413 diabetic patients with STEMI and high thrombus burden, we examined the merit of intracoronary GPI and vasodilator agents combined with aspiration thrombectomy vs aspiration thrombectomy alone. We found that intracoronary GPI and vasodilator agents combined with aspiration thrombectomy improved the markers of coronary microvascular flow such as MBG 3, reduced cTFC, and TIMI 3 flow. In addition, intracoronary vasodilator agents combined with aspiration thrombectomy was associated with better left ventricular EF. These findings suggest that a strategy of combined of intracoronary GPI and vasodilator agents with aspiration thrombectomy might be beneficial among diabetic patients presenting with STEMI and high thrombus burden. Given the limited available therapeutic strategies to mitigate the risk of adverse events among this high-risk group, our findings provide a rationale to evaluate a strategy combined of intracoronary vasodilator agents with aspiration thrombectomy in a larger clinical trial.

Aspiration catheters can be useful for local drug injection, not only thrombus aspiration. Local injection delivers the drug effectively to the infarct-related artery. However, when using a guiding catheter to infuse intracoronary agent, it is likely that a significant portion of the drug will not reach the target artery but rather will follow the blood stream into the coronary branches with normal flow. This is one of the potential mechanisms to explain the high rates of slow flow, or no-reflow in lesions with high thrombotic burden (due to microvascular obstruction) which is associated with an increased infarct size, reduced recovery of ventricular function, and worse outcomes.18

Randomized clinical trials demonstrated that routine aspiration thrombectomy improves the markers of coronary microvascular perfusion as MBG, TIMI flow and ST resolution, however; this was not translated into a benefit on clinical outcomes as mortality and re-infarction19–21 and might increase the risk of stroke.22,23 In a patient level analysis of the 3 largest trials of routine aspiration thrombectomy, aspiration thrombectomy was associated with a trend of benefit among the subgroup of patients with high thrombus burden.24 Accordingly, the American and European guidelines recommend against routine aspiration thrombectomy among all-comers with STEMI, but suggest that aspiration thrombectomy could be considered among patients with high thrombus burden.1,25 This randomized trial extended our knowledge by demonstrating that a strategy of combined of intracoronary GPI and vasodilator agents with aspiration thrombectomy might be of benefit among diabetic patients with STEMI and high thrombus burden.

The INFUSE-AMI trial26 and a meta-analysis27 suggested that a combination of aspiration thrombectomy and abciximab administration is the most efficient treatment for decreasing infarct size compared with each treatment alone or no treatment with aspiration thrombectomy or abciximab. These findings are consistent with our study. If most thrombotic materials are retrieved by aspiration thrombectomy, intracoronary abciximab could further dissolve residual in situ thrombus as well as microemboli in the microvasculature. Another randomized trial demonstrated the lack of benefit of intracoronary high-dose adenosine or sodium nitroprusside on microvascular circulation, and a possible deleterious effect of adenosine.28 Our study included only diabetic patients which are prone to higher platelet activity and worse microvascular function, offering promising results.

The results of this study showed that in patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI, local delivery of GPI and vasodilator agents via thrombus aspiration catheter yields a greater dissolution of the thrombus burden than thrombus aspiration alone as evident by the improvement in flow parameters of reperfusion success. However, we noted that the rates of ST-segment resolution were not different between both groups. These results can be further tested in future trials to determine its implication on clinical outcomes in diabetic patients with large thrombus burden. Future studies should also investigate whether this benefit could be achieved obtained by the combination of GPI and vasodilators or by any of them individually, and whether these intracoronary therapies would improve microcirculatory resistance index and coronary flow reserve. Finally, studies addressing if this approach could be extended to nondiabetic patients would be of interest.

LimitationsThe findings of this study should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, inclusion of only diabetic patients would make our findings not generalizable to all-comers with STEMI undergoing primary PCI. Second, we were unable to discern whether the improvement in the primary endpoint is due to the combination of the GPI and vasodilators or whether this improvement may be due only to one of the two components separately. Third, the sample size and relatively short duration of follow-up likely contributed to the low number of clinical events. Fourth, while the assessment of the angiographic outcomes was blinded, the assessment of the clinical endpoints was not. Fifth, this study was not placebo-controlled which could reduce the comparability of both arms. Finally, benefits such as ability to perform direct stenting or reduced stent length were not examined.

CONCLUSIONSIn diabetic patients with STEMI and high thrombus burden, distal intracoronary eptifibatide plus vasodilators injection shows more benefit in preventing no-reflow and associated with improved EF, cTFC and MBG compared to thrombectomy alone.

FUNDINGAuthors did not receive any external fund for this work.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSM. Hamza: collecting data, results statistics, and writing. I Elgendy: writing, editing, and revising.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- -

In this research we studied the effect of distal intracoronary injection of eptifibatide with vasodilators to prevent against no-reflow if routine balloon dilatation fails to open the artery with no visualization of the distal bed.

- -

We report a new technique that may add some benefit to prevent against no-reflow in STEMI patients with high thrombus burden.