The importance of measuring patient satisfaction in healthcare is clearly acknowledged in the literature. Measuring satisfaction is a way of monitoring management actions and might also provide information about the quality of the service and future patient behavior, such as treatment adherence.

How to measure satisfaction is still a widely debated issue, because of the complexity of the concept and the divergent options proposed for its measurement.1 One of the key controversies about this topic is how to generate the attributes or factors linked to satisfaction.

We propose a way of eliciting satisfaction attributes in a cardiology service by employing associative maps, associative priming, and the first-person data approach.2,3

We collected a sample of 50 consecutive patients in a Spanish public hospital, who were admitted to the cardiology ward from March 1 to 18, 2018. A simple questionnaire was provided before the patients were discharged, in which participants had only to freely indicate attributes/concepts that they linked to satisfaction with the service received. Using the above-mentioned method, we obtained individual associative maps, which were finally aggregated in a consensus map representing the main shared satisfaction attributes and their weights. Thirteen questionnaires were excluded because of unintelligible and nonvalid responses and therefore the final sample analyzed was composed of 37 participants (78% men, mean age 64.7 years). The order of mention of each attribute represented its hierarchy in the mind of the patient, ie, its weight or importance in the definition of overall satisfaction. Then we used the frequency of mention to select the attributes for the final consensus map, weighting its importance using a power law function y=ax−k, which is a ubiquitous characteristic of learning, memory, and sensation,4 where y is the importance of the attribute, x is the order of mention, a is a constant, and k is a parameter that can be estimated. We simplified the prior expression using a=1 and fixing k=1 to obtain a nonlinear decay of y with x. For example, if a patient mentioned 4 attributes, the weights were, respectively: 1.00, 0.50, 0.33, and 0.25. More generally, if n participants mentioned j disparate attributes, z being the total number of mentions, then we summed the disparate weights for each attribute j over the whole sample n, and then we divided it by z. Consequently, we obtained an index of importance for each attribute ranging from 0 to 1.

The next step was to propose a threshold point within that (0-1) interval and/or to the frequency of mention, to select the final attributes for the consensus map. We employed a statistical threshold by which only associations with a frequency of mention higher than 20% were included.

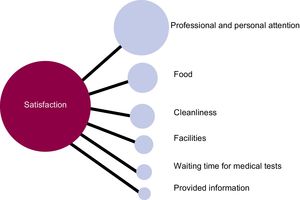

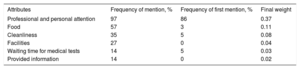

The results of the aggregation procedure are shown in the Table and Figure. Only 6 concepts were mentioned in the sample: a) professional and personal attention; b) appetizing food; c) cleanliness; d) facilities; e) waiting time for medical tests; and f) the information provided. The first 4 attributes had a frequency of mention higher than 20%, and the 2 latter had an exact binomial 95%CI, 4.5% to 28.8%, containing the cutoff value of 20%. Therefore, all the attributes were finally chosen and their importance was determined by their final weight.

Attributes of Satisfaction for the Aggregated Sample

| Attributes | Frequency of mention, % | Frequency of first mention, % | Final weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional and personal attention | 97 | 86 | 0.37 |

| Food | 57 | 3 | 0.11 |

| Cleanliness | 35 | 5 | 0.08 |

| Facilities | 27 | 0 | 0.04 |

| Waiting time for medical tests | 14 | 5 | 0.03 |

| Provided information | 14 | 0 | 0.02 |

Of note, professional and personal attention was the most important concept linked to patient satisfaction. It was freely ranked first by 86% of participants, and it comprised the valence of the service (professional performance) and the quality of personal interaction (human interaction with health care workers).

The final consensus map (Figure) shows the 6 attributes represented as nodes linked to the core concept of satisfaction. The area of each of the 6 circles represents the relative weight of each attribute or, equivalently, its relative area with respect to the area of the satisfaction node. Remember that, if only a single attribute would have been freely mentioned by the whole sample, its weight would have been 1.00, so the area of the central node (satisfaction) and the area of the single elicited attribute would have been the same, because in fact, both concepts would have really meant the same. However, the pattern of responses of our sample shows that patient satisfaction was associated with several aspects of the service, revealing that overall satisfaction is a complex concept that is defined differently by each patient.

We have presented a simple but powerful new method to measure patient satisfaction in a cardiology service, which combines associative priming and a first person-data approach to elicit concepts associated with satisfaction. By means of this method we have overcome some of the limitations of structured questionnaires. Then, after following a method of aggregating these associations,3,5 a final consensus map was obtained, providing useful information about the importance of the attributes. In-depth knowledge of these attributes might be crucial to design strategies to improve patient satisfaction and potentially to improve health care.

FUNDINGJ.A. Martínez acknowledges the financial support from project ECO2015-65637-P (MINECO/FEDER). This study is the result of the activity carried out under the Excellence Grops program of the Región of Murcia, the Fundación Séneca, Science and Technology Agency of the region of Murcia project 19884/GERM/15.