Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is infrequent in young patients. In these cases, specially in the absence of classical cardiovascular risk factors, discarding thromboembolic disease risk factors, such as use of oral contraceptives, thrombophilia and certain cardiac malformations, is mandatory. Interatrial septum aneurysm (ASA) and paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale (PFO) in presence of thrombosis are some examples of the latter.

CASE PRESENTATION

The case presented is a 33 year old female that arrived to the emergency department referring typical chest pain lasting for 90 min. The patient had a history of smoking and used third generation oral contraceptives.

In the electrocardiogram, ST elevation in the anterior region was found. Thrombolysis with plasminogen tissue activator was performed, after which clinical and electrocardiographic criteria for reperfusion were observed. A few minutes after administering the thrombolitic agent, the symptoms of angina reappeared and ST elevation was observed in inferior, posterior and lateral regions. The patient underwent urgent coronary angiography. Occlusions of the distal anterior descending artery, the second diagonal origin and the ramus were demonstrated. No angiographic stenosis suggestive of underlying atherosclerotic disease (Figure 1) was found.

Fig. 1. Coronary angiography showing multiple coronary embolisms.

A transthoracic echocardiographic examination (TTE) was performed next, detecting an inferior and anterior akinesia, a severely impaired global LV function, an image of intraventricular thrombus and an ASA (Figure 2). The patient received anticoagulant therapy and outcome was satisfactory during hospital stay; neurological symptoms did not appear.

Fig. 2. Transesophagic echocardiographic examination image showing an aneurysm of the interatrial septum. AD indicates right atrium; AI, left atrium.

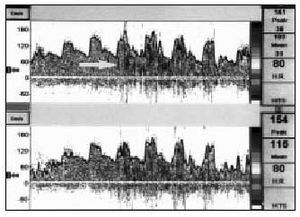

The transesophagic echocardiographic examination (TEE) performed did not show right-to-left shunt with the Valsalva maneuver (after injection of agitated saline solution), although the patient did not cooperate optimally during the examination. A transcraneal Doppler (TCD), also injecting saline solution after Valsalva maneuver, confirmed the existence of a massive right-to-left shunt through a PFO (Figure 3). The thrombophilia study also detected that the patient was heterozygotic for the factor II prothrombotic variant (G20210A). The remaining coagulation parameters were normal. Tests for detecting deep venous thrombosis were not performed.

Fig. 3. Transcraneal pulsed-Doppler study of the mid cerebral artery (MCA), in which a massive right-to-left shunt can be observed after injection of saline solution during the Valsalva maneuver. The arrow indicates the shunt artifact (showering pattern) in the MCA interfering with the normal velocity curve frequency spectrum.

The patient received dicumarinic anticoagulant therapy and was discharged. She remains asymptomatic after 2 years of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

This case is specially interesting as it is infrequent to find various coronary occlusions originated by embolism in a young female with multiple risk factors for thromboembolic disease. One of these risk factors is the factor II prothrombotic variant (G20210A), present in 1%-2% of the general population, and in 18% of thrombophilia cases. Its presence has been demonstrated to double or even triplicate the risk of venous thrombosis. The association with arterial thrombosis is more controversial,1-3 although evidences are clearer when it coexists with classical risk factors, mainly smoking.1

The use of oral contraceptives increases AMI risk, specially in smoking females older than 40 years.4 As atherosclerotic lesions do not appear in the coronary angiographies performed on smoking patients that use contraceptives, we postulate a prothrombotic state as the AMI mechanism.

ASA is present in 2.2% of the general population,5 while a PFO is detected in 56% of patients with ASA. PFO prevalence in the general population is 25% to 30%.

A higher prevalence of paradoxical embolism, both cerebral6,7 and coronary, has been described in these patients, particularly when the shunt through the PFO is moderate or severe.8-10 Other authors have not observed a higher PFO incidence in AMI patients with normal coronary arteries,11 although TTE, less sensitive than TEE for PFO detection, were used in this study without measuring the shunt. The TEE and the TCD study are used for diagnosticating PFO, and though false negatives exist in both techniques, they are considered complementary for its diagnosis.9 Echocardiographic examinations are absolutely necessary for the morphologic study, while both TEE and TCD are useful for shunt measurement.8

In patients with right-to-left shunts due to suspected paradoxical embolism, performance of an isotopic phlebography is recommended, as 10% of these patients present deep venous thrombosis asymptomatic in 80% of cases.12

The exact mechanism that caused multiple coronary embolism in this case cannot be defined. All the factors mentioned here increase the risk, particularly when several coincide. Possibly, the embolic cause originated in the venous area and accessed the systemic circulation through the PFO, or proceeded from the intraventricular thrombus fragmentation; this was favored by the patient´s prothrombotic state (oral contraceptives and presence of G20210A). This is an exceptional clinical case, as multiple embolization of the coronary arteries was observed in absence of angiographic stenosis suggestive of an underlying arteriosclerotic disease.

Correspondence: Dra. I. Antorrena Miranda.

Belando, 20, 3.o A. 03004 Alicante. España.

E-mail: iantorrena@hotmail.com

Received 15 April 2002.

Accepted for publication 14 October 2002.