The prevalence of Chagas disease (CD) has been increasing globally.1 In the United States, CD was reported in approximately 300 000 people, while cases have also been identified in Europe.1,2 The reactivation rate of CD in transplant recipients displays variability, ranging from 40% to 61%.3,4 This reactivation is determined through positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results, endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) findings, or symptomatic disease. Here we describe 4 clinical cases of Neurochagas (NCh) from a single center. Notably, our hospital does not routinely adopt immunosuppressive induction therapy. Nonetheless, a uniform approach was observed across all cases, involving the administration of preoperative intravenous corticosteroids. The standard immunosuppressive regimen used for maintenance includes cyclosporine or tacrolimus, sodium mycophenolate, and prednisone. However, the patients diagnosed with CD deviated from this regimen, with azathioprine substituting mycophenolate.4 Informed consent was obtained from all 4 patients.

The first case is a 45-year-old male presenting with CCM (CCM) and advanced heart failure (HF) criteria, who underwent bicaval orthotopic heart transplant (BOHT) in 2014. Following discharge, he received tacrolimus, prednisone, and mycophenolate due to an inability to tolerate azathioprine. However, 3 months after discharge, he was admitted to hospital due to frontal headache and a single episode of generalized seizures (GS). Upon physical examination, an inflammatory nodule was observed in the left lower limb, which was positive for Chagas panniculitis in a biopsy. Cranial computed tomography (CT) showed a hypoattenuating left frontal area. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exhibited a cortico-subcortical area of heterogeneous signal in the same region. Consequently, the diagnostic hypothesis of NCh was considered. Benznidazole was promptly initiated, accompanied by a reduction in immunosuppressants. The patient made favorable progress, with no further episodes of GS reported.

The second case is a 48-year-old male, meeting the criteria for advanced HF due to CCM, who underwent BOHT in 2020. Within the first month after theart transplant (HT), he experienced ventricular dysfunction (40%) while taking the drugs detailed in table 1. EMB indicated grade 2R cellular rejection, leading to the administration of methylprednisolone therapy, which subsequently resulted in improved ventricular function. However, he showed GS controlled with anticonvulsants. Imaging from both CT and MRI suggested posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, and CSA was replaced with tacrolimus. Three weeks later, he had another GS, accompanied by dysarthria, reduced level of consciousness, and left hemiparesis. An MRI scan was performed, revealing a cerebral lesion. Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed the presence of trypomastigotes (video 1 of the supplementary data). Benznidazole was introduced, coupled with a reduction in CSA. The patient is currently undergoing rehabilitation with partial improvement.

Clinical features and radiological characteristics at the time of presentation

| Clinical features | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chagas serology | Seizures | Headache | Hemiplegia | Level of consciousness | Dysarthria | Extraneurological presentation | |

| Case 1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ (panniculitis) | ||

| Case 2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Case 3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Case 4 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Radiological characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomography findings | Resonance findings | ||||

| Enlargement of cisterns | Hypoattenuating area | Ventricles dilation | Enhance post contrast | White matter lesion | |

| Case 1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Case 2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Case 3 | √ | √ | |||

| Case 4 | √ | √ | |||

| Pre- and postreactivation data | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV PCR | EMB/PCR test | TTE | Fungus, toxoplasmosis | Immunosuppression before reactivation | Background rejection > 2R | Pulse therapy | Serum level ng/ml | Immunosuppression after reactivation | |

| Case 1 | Negative | 0R/PCR (-) | Normal | Negative | MMF 720 mg bidTacrolimus 5 mg bid Prednisone 20 mg qd | No | No | 22 | AZT 50 mg bid Tacrolimus 4 mg bid Prednisone 10 mg qd |

| Case 2 | Negative | 0R/PCR (+) | Normal | Negative | AZT 50 mg bid CSA 200 mg bid Prednisone 40 mg qd | Yes | Yes | 391 | AZT 50 mg bid CSA 175 mg bid Prednisone 10 mg qd |

| Case 3 | Negative | 1R/PCR (+) | Normal | Negative | AZT 50 mg bidCSA 175 mg bidPrednisone 20 mg qd | No | No | 425 | AZT 50 mg bidCSA 150 mg bidPrednisone 5 mg qd |

| Case 4 | Negative | 1R | Normal | Negative | MMF 500 mg bidCSA 200 mg bidPrednisone 10 mg qd | Yes | No | MMF 500 mg bidCSA 200 mg bidPrednisone 10 mg qd | |

AZT, azathioprine; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CSA, cyclosporine; EMB, endomyocardial biopsy; MMF, mycophenolate; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; bid, twice a day; qd, once a day; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram.

The third case is a 47-year-old male diagnosed with CCM, and advanced HF who underwent BOHT in 2022. On the third postoperative day, he experienced a GS. A CT scan revealed a hypoattenuating frontal subcortical area on the left. One month after HT, another GS occurred. Despite initiation of anticonvulsant therapy, the GS persisted. Subsequent cranial MRI exhibited a lesion consistent with chagoma. Further, Trypanosoma cruzi was detected in CSF. The dose of CSA was decreased and benznidazole was started, resulting in the absence of subsequent GSs.

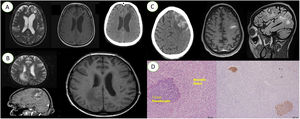

The fourth case is a 46-year-old male meeting the criteria for advanced HF due to CCM, who underwent BOHT in 2002. Five months following the HT, he was hospitalized due to GS accompanied by lowered level of consciousness and left hemiplegia. The immunosupression drugs are detailed in table 1. A CT scan identified a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Unfortunately, the patient progressed to brain death and an autopsy was performed. Amastigote nests were evident in the excisional brain biopsy (figure 1).

A. From left to the right; cranial magnetic resonance image with dilatation of ventricles and subcortical area of heterogeneous signal in the left frontal region; T1 sequence, with hyposignal in the same region; cranial computed tomography scan with hypoattenuating left frontal area.

B. From left to the right; cranial magnetic resonance imaging with hypersignal in the frontoparietal transition; T2 flair magnetic resonance imaging scan shows hypersignal in the same region; axial magnetic resonance imaging scan showing hyposignal.

C. From left to the right; cranial computed tomography with hyperdensity in the left frontal cortical sulci; magnetic resonance imaging scan showing a chagoma in the same region; magnetic resonance imaging scan showing the same chagoma.

D. From left to the right; histological section with the presence of Trypanosoma cruzi pseudocysts; immunostaining for Trypanosoma cruzi showing the presence of pseudocysts.

The clinical presentation of CD may manifest asymptomatically or even as myocarditis or encephalitis with stroke. The most frequently used diagnostic methods are blood PCR analysis, CSF analysis, and EMB.3 According to our data, the incidence of NCh was of 4 cases (2.9%) from 2013. The prevalence of reactivation with neurological compromise has not been extensively documented, and a retrospective trial reported a prevalence of 3.1%.4 This reactivation rate is not commonly reported, including in transplants of other organs.5,6 At our institution, pretransplant PCR monitoring is not part of our routine practice. However, posttransplant PCR monitoring is conducted when specific risk factors are present, in cases of clinical suspicion, or even in asymptomatic patients, along with each EMB. A PCR test for CD was performed in 3 patients reported in table 1.

The neurological clinical symptoms observed in our series were hemiplegia, seizures, dysarthria, and altered level of consciousness. Among the radiological features, the most frequent were hypoattenuating areas, enlargement of the cisterns, and dilation of the ventricles. In our center, treatment with benznidazole is immediately started and the immunosuppressant dose is reduced. Benznidazole is used for 60 days, but there have been no reports of the treatment and duration of reactivation with central nervous system involvement.2 There is no consensus on the benefits of using prophylactic benznidazole in patients with CD who undergo HT.

The main recommendations of this study are as follows: identify risk factors predisposing to reactivation, establish a lower threshold when deciding on the degree of immunosuppression, and frequently monitor these patients during follow-up through clinical suspicion and complementary analyzes (EMB, PCR).

FUNDINGThe authors declare that they have not received any funding for this work.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONSInformed consent was obtained from all 4 patients. The present manuscript has received approval from the ethics committee of our institution. The manuscript was prepared in accordance with the SAGER guidelines and the potential variables related to sex and gender were not relevant.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCEThe artificial intelligence did not play a role in the creation of this work.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSC. Espinoza Romero, D. Catto de Marchi, F.G. Marcondes-Braga, S. Mangini, M. Samuel Avila and F. Bacal contributed to all aspects of this manuscript including study planning and design, model development, performing experiments, data collection and analysis, preparation, and review of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.

To the Infectious Diseases unit (Dr. Tânia Strabelli), Pathology (Dr. Paulo Sampaio Gutierrez) and the members of the heart transplant unit of the Instituto do Coração, São Paulo, Brazil.