The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of colorectal disease in Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis (EFIE) patients.

MethodsAn observational, retrospective, multicenter study was performed at 4 referral centers. From the moment that a colonoscopy was systematically performed in EFIE in each participating hospital until October 2018, we included all consecutive episodes of definite EFIE in adult patients. The outcome was an endoscopic finding of colorectal disease potentially causing bacteremia.

ResultsA total of 103 patients with EFIE were included; 83 (81%) were male, the median age was 76 [interquartile range 67-82] years, and the median age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index was 5 [interquartile range 4-7]. The presumed sources of infection were unknown in 63 (61%), urinary in 20 (19%), gastrointestinal in 13 (13%), catheter-related bacteremia in 5 (5%), and others in 2 (2%). Seventy-eight patients (76%) underwent a colonoscopy, and 47 (60%) had endoscopic findings indicating a potential source of bacteremia. Thirty-nine patients (83%) had a colorectal neoplastic disease, and 8 (17%) a nonneoplastic disease. Of the 45 with an unknown portal of entry who underwent a colonoscopy, gastrointestinal origin was identified in 64%. In the subgroup of 25 patients with a known source of infection and a colonoscopy, excluding those with previously diagnosed colorectal disease, 44% had colorectal disease.

ConclusionsPerforming a colonoscopy in all EFIE patients, irrespective of the presumed source of infection, could be helpful to diagnose colorectal disease in these patients and to avoid a new bacteremia episode (and eventually infective endocarditis) by the same or a different microorganism.

Keywords

Enterococci are normal commensals of the gastrointestinal tract and are able to cause infection by translocation through the epithelial cells of the intestine, gaining access to the lymphatic system and bloodstream through mechanisms that have not yet been elucidated.1,2 Therefore, lesions in the colonic mucosa could be a portal of entry of bacteremia, such as in Streptococcus gallolyticus infective endocarditis (IE).3,4

In developed countries, Enterococcus faecalis is the third cause of IE.5E. faecalis infective endocarditis (EFIE) affects older patients with comorbidities,6–8 a population with a higher incidence of colorectal disease.9 Moreover, 5% of patients with IE regardless of the etiology will have an additional episode of IE with a higher mortality risk.10 Therefore, identifying the portal of entry and treating it are particularly important to lower the risk for a new IE episode.11,12

A recent retrospective study performed in a selected cohort of patients showed that patients with EFIE of unknown origin had a higher prevalence of colorectal lesions (31 of 61, 50.8%) than those with EFIE with a known origin (1 of 6, 16.7%); however, in that study a colonoscopy was not systematically performed in all patients, particularly not in EFIE patients with a presumed known source of infection.13 Considering the importance of controlling potential portals of entry in EFIE to avoid new bacteremia by the same or a different microorganism,11 the question arises of whether to systematically perform a colonoscopy in patients with EFIE.

The objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of colorectal disease in patients with EFIE, regardless of whether the infection source was known.

METHODSDesign, setting, and patientsThis observational, retrospective, multicenter study was performed at 4 referral centers for IE: Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (HUVH), a 1000-bed teaching hospital in Barcelona (Spain), Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo (CHUV), a 1200-bed teaching hospital in Vigo, Pontevedra (Spain), Presidio Ospedaliero Universitario Santa Maria della Misericordia (POUSMdM), a 1000-bed teaching hospital in Udine (Italy), and Hospital de Barcelona (HdB), a 250-bed private hospital in Barcelona (Spain). All 4 centers are referral centers for cardiac surgery.

Considering the importance of controlling the portal of entry to avoid recurrences, since January 2014 a colonoscopy has been systematically performed in EFIE patients at POUSMdM, since July 2014 at HUVH, and since January 2015 at CHUV, and HdB. From the moment that a colonoscopy was systematically performed in each participating hospital until October 2018, all consecutive episodes of definite EFIE in adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) were included in the study. Only the first episode of EFIE in each patient was recorded. Patients were retrospectively identified from the Infectious Diseases Registry of each participating hospital, in which all consecutive episodes of IE are prospectively recorded.

EndpointsThe endpoint was an endoscopic finding of colorectal disease that could potentially cause bacteremia.

Variables related to infective endocarditisThe definition of variables related to IE can be found in detail in the methods of the supplementary data.14–20

Variables related to colonoscopyWe included all colonoscopies performed after the onset of IE symptoms or 6 months before EFIE diagnosis, as well as those performed during treatment and 6-month follow-up. Assessment of bowel preparation was performed according to gastroenterologist reports and was classified as good (no fecal remains or very few that allowed an adequate surface examination), average (some semisolid stool that could be suctioned or washed away and allowed adequate surface examination) or poor (abundant fecal remains that could not be suctioned or washed away and that prevented adequate surface examination),21 and the possibility of cecal intubation was recorded.

Endoscopic findings of the colonoscopy and adverse events were also recorded. Adverse events related to the procedure included colonic perforation, lower gastrointestinal bleeding, and allergic reactions to sedative medication.

We recorded all endoscopic findings. We did not include uncomplicated diverticula and uncomplicated hemorrhoids to be a potential cause of bacteremia. Among any endoscopic findings that could potentially cause bacteremia, we classified colonic lesions into neoplastic and nonneoplastic diseases according to the histopathological report. We conducted the classification based on the most advanced lesion identified. If no histopathological report was available, we classified the lesion as nonneoplastic.

Colorectal neoplasms included colorectal adenomas and colorectal carcinomas. Adenomas were divided into nonadvanced colorectal adenomas (tubular adenomas with a diameter <10 mm) or advanced colorectal adenomas (adenomas measuring ≥ 10 mm, with villous architecture, high-grade dysplasia, or intramucosal carcinoma). The criterion for colorectal carcinoma was the presence of malignant cells beyond the muscularis mucosae.22 Nonneoplastic diseases included colonic mucosal inflammation, angiodysplasias, ulcers, and nonneoplastic polyps. All patients with endoscopic findings were referred to the gastroenterologist for follow-up.

Data collectionDemographic, clinical, diagnostic, treatment, outcome and follow-up data were obtained from the prospective IE registry of each center. Data on colonoscopy (date of performance, pathological findings, and adverse events) were retrospectively collected from the patients’ medical charts and entered in a database created specifically for this study.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are reported as the median and interquartile range [IQR], and qualitative variables as number and percentage. Differences between patients according to the source of infection or the presence or absence of endoscopic findings in colonoscopy were assessed by the chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate, and the 2-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test for continuous variables. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software, version 15. A 2-tailed P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

EthicsThe study was approved by the hospital ethics committee of Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona (Spain), (approval PR(AG)332/2018) and the remaining participating centers. Informed consent from patients was not required.

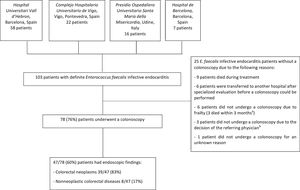

RESULTSPatients included in the studyA total of 103 episodes of definite EFIE were included in the study. Of these cases, 78 (76%) patients underwent a colonoscopy (figure 1). Of those with a colonoscopy, 47 (60%) had endoscopic findings indicating a potential source of bacteremia. The epidemiological, clinical, and outcome characteristics are shown in .

Flowchart. a The reasons were acute pulmonary edema, bronchoaspiration, and hematologic malignancy, respectively. b One patient had a previous urinary tract infection due to E. faecalis, 1 patient was a 32-year-old woman with recurrent urinary tract infections, and 1 patient had undergone a hemicolectomy for a colon adenocarcinoma 8 months previously.

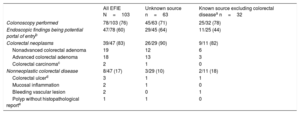

Table 1 shows the endoscopic findings in all patients undergoing a colonoscopy and divided by groups depending on whether the source of infection was known (excluding patients with previously diagnosed colorectal disease) or unknown. For more detailed information see .

Colonoscopy findings among all patients with EFIE and according to known or unknown source of infection

| All EFIE N=103 | Unknown source n=63 | Known source excluding colorectal diseasea n=32 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonoscopy performed | 78/103 (76) | 45/63 (71) | 25/32 (78) |

| Endoscopic findings being potential portal of entryb | 47/78 (60) | 29/45 (64) | 11/25 (44) |

| Colorectal neoplasms | 39/47 (83) | 26/29 (90) | 9/11 (82) |

| Nonadvanced colorectal adenoma | 19 | 12 | 6 |

| Advanced colorectal adenoma | 18 | 13 | 3 |

| Colorectal carcinomac | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Nonneoplastic colorectal disease | 8/47 (17) | 3/29 (10) | 2/11 (18) |

| Colorectal ulcerd | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Mucosal inflammation | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Bleeding vascular lesion | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Polyp without histopathological reporte | 1 | 1 | 0 |

EFIE, Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis.

Data are expressed as No. or proportion (%).

Regarding digestive source, we included 5 cases with a presumed hepatobiliary source of infection: 2 cholangitis, 2 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies, and 1 radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. We excluded 8 cases of colorectal disease diagnosed during the 3-months prior to endocarditis diagnosis: 3 colitis (1 infectious with a polyp found in the colonoscopy, 1 ischemic with mucosal inflammation and the other also presumed to be ischemic without pathological findings in the colonoscopy), 3 lower gastrointestinal bleedings (1 due to vascular lesions, 1 due to an advanced colorectal carcinoma, and 1 due to a colorectal ulcer), 1 rectal carcinoma, and 1 recent polypectomy.

Of the 78 patients who underwent a colonoscopy, 47 (60%) had endoscopic findings indicating a potential source of bacteremia. Thirty-nine patients (83%) had a colorectal neoplastic disease, and 8 (17%) had a nonneoplastic disease. Of the 39 patients with a colorectal neoplasm, 19 had a nonadvanced colorectal adenoma, 18 had an advanced colorectal adenoma, and 2 had a colorectal carcinoma. Of the 8 patients with a nonneoplastic disease, 3 patients had nonmalignant ulcers, 2 patients had colorectal mucosa inflammation (1 due to ischemic colitis and the other to radiation proctitis), 2 patients had angiodysplasias, and 1 patient had a polyp without a histopathological report.

A colonoscopy was available in 45 (71%) of the 63 patients with an unknown source of infection, 25 (78%) of the 32 patients with a known source of infection (including urinary tract, hepatobiliary source, catheter-related bacteremia source and other sources), and all 8 patients with a previously diagnosed colorectal disease as the presumed source of infection. Of 45 patients with an unknown portal of entry who underwent a colonoscopy, a potential gastrointestinal origin was identified in 29 (64%). Of 25 patients with a known source of infection and a colonoscopy, excluding those with previously diagnosed colorectal disease, 11 (44%) patients had colorectal disease ().

Bowel preparation and adverse events related to colonoscopyBowel preparation was considered good in 27 colonoscopies, average in 42 colonoscopies, poor in 6 colonoscopies and was not available in 2 colonoscopies. Cecal intubation was feasible in 74 patients (95%), and unknown in 1 patient. A polypectomy was performed in all 38 patients with polyps, and a biopsy was performed in 3 patients (1 of the 3 ulcers and in 2 suspected colorectal carcinomas).

Regarding complications, 4 (5%) patients had lower gastrointestinal bleeding. All bleedings occurred after polypectomy for advanced adenomas at a median of 10 days, including 2 cases in patients receiving acenocoumarin (both patients required red cell transfusion) and the other 2 in patients receiving enoxaparin (1 patient also required red cell transfusion). A second colonoscopy was performed in the 4 patients with bleeding, and endoscopic hemoclips were placed in 3 patients. There were no reported colonic perforations or allergic reactions to sedative medication.

Comparison of patient characteristics according to the presence or absence of endoscopic findingsTable 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the EFIE patients according to the presence or absence of relevant endoscopic findings. Age and comorbidities were similar. There were no significant differences between the presumed sources of infection, although an unknown origin and gastrointestinal source had more endoscopic findings than the urinary tract. Complications, surgical treatment, and outcomes were similar in the 2 groups, with the exception of the only 2 relapses that both occurred in patients with relevant endoscopic findings and neither had previous surgical indication. One patient received 26 days of intravenous antibiotic therapy and relapsed at day 23 after treatment completion. Colonoscopy was performed during treatment of the first episode of EFIE, and small ulcers were identified in the sigmoid colon. The other patient received 44 days of treatment and relapsed at day 48 after completing antibiotic treatment with negative blood cultures in between. Colonoscopy was performed 14 days after relapse, not during the treatment of the first episode of EFIE, and 3 nonadvanced adenomas and 1 advanced adenoma were identified.

Demographic features, comorbidities, presumed source of infection, complications, surgical treatment, and outcomes of episodes of Enterococcus faecalis IE depending on the presence or absence of relevant endoscopic findings in the colonoscopy

| No endoscopic findingsn=31 | Endoscopic findingsn=47 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 76 [67-82] | 75 [67-82] | .842 |

| Male sex | 24 (77) | 38 (81) | .713 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Aged-ajusted Charlson comorbidity index | 5 [3-6] | 5 [3-6] | .800 |

| Previously diagnosed known colonic disease | 7 (23) | 15 (32) | .370 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (26) | 13 (28) | .857 |

| Chronic renal failure | 7 (23) | 11 (23) | .933 |

| Neoplasm | 4 (13) | 4 (9) | .706 |

| Transplantation | 2 (6) | 4 (9) | 1 |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | 2 (6) | 5 (11) | .697 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 |

| Healthcare-associated infection | 14 (45) | 22 (47) | .886 |

| Presumed source of infection | |||

| Unknown | 16 (52) | 29 (62) | .377 |

| Urinary | 9 (29) | 7 (15) | .130 |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (10) | 9 (19) | .344 |

| Catheter-related bacteremia | 2 (6) | 2 (4) | 1 |

| Othersa | 1 (3) | 0 | .397 |

| Positive urine culture for E. faecalis at the same time as positive blood cultures | 5/28 (18) | 7/41 (17) | 1 |

| Symptom duration, d | 32 [9-38] | 17 [6-48] | .759 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 10.7 [9.7-12] | 10.3 [9.4-11.5] | .567 |

| Ferritin, ng/mLb | 274 [134-488] | 284 [205-476] | .615 |

| Transferrin saturation, %c | 12 [9-19] | 15 [9-25] | .297 |

| Type of IE | |||

| Native valve IE | 19 (61) | 26 (55) | .601 |

| Prosthetic valve IE | 10 (32) | 20 (43) | .360 |

| Cardiac implantable electronic device | 2 (6) | 1 (2) | .560 |

| Heart valve affected | |||

| Aortic | 16 (52) | 23 (49) | .871 |

| Mitral | 8 (26) | 16 (34) | .441 |

| Aortic and mitral | 5 (16) | 8 (17) | .918 |

| Tricuspid | 1 (3) | 0 | .397 |

| Unknown | 1 (3) | 0 | .397 |

| Complications (some patients had > 1 complication) | 18 (58) | 32 (68) | .367 |

| Heart failure | 8 (26) | 19 (40) | .184 |

| Symptomatic embolism | 7 (23) | 5 (11) | .203 |

| New renal failure | 5 (16) | 7 (15) | 1 |

| Paravalvular complication | 5 (16) | 7 (15) | 1 |

| Stroke | 3 (10) | 6 (13) | 1 |

| Surgery indicated (some patients had> 1 indication) | 15 (48) | 19 (40) | .488 |

| Heart failure | 9/15 (60) | 12/19 (63) | .733 |

| Uncontrolled infection | 5/15 (33) | 8/19 (42) | .918 |

| Embolism prevention | 5/15 (33) | 3/19 (16) | .254 |

| Cardiac implantable electronic device infection | 2/15 (13) | 1/19 (5) | .560 |

| Surgery performed during the active phase of infection (if indicated) | 12/15 (80) | 14/19 (74) | 1 |

| Duration of antimicrobial treatment (d) in all patients | 43 [41-46] | 42 [41-48] | .829 |

| Duration of antimicrobial treatment (d) in survivors | 43 [42-47] | 43 [42-49] | .926 |

| Mortality during treatment | |||

| Overall | 2/31 (6) | 3 (6) | 1 |

| Surgery indicated not performed | 2/31 (6) | 1 (2) | .464 |

| Surgery indicated and performed | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 |

| No surgery indicated | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 |

| Follow-up in survivors after finishing antibiotic treatment (mo) | 6.4 [3.9-9.9] | 9.3 [4.6-19.3] | .081 |

| 3-months mortality | 2/29 (7) | 2/44 (5) | 1 |

| Surgery during follow-up | 0 | 3/44 (7) | .272 |

| Relapse | 0 | 2/44 (5) | .515 |

IE, infective endocarditis; IQR, interquartile range.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range].

Our results demonstrate that a potential source of bacteremia arising in the bowel is frequent in EFIE, irrespective of whether another source of infection is already suspected; thus, colonoscopy should be considered in these patients.

In IE, it is fundamental to identify and to control the presumed source of the bacteremia to eradicate it and decrease the risk of a new IE episode by the same or a different microorganism.12 Previous studies have suggested performing a colonoscopy if the microorganism causing the IE may have originated in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in patients aged ≥ 50 years, as well as in those with a familial history of colonic polyposis.11,23,24 As the presumed source of infection in EFIE is often unknown,8,13 colonoscopy could be useful to identify a source. Moreover, as enterococci are found in the gastrointestinal tract and the population at risk of EFIE are older6,7 and have a higher incidence of colorectal disease,9 even though there is a clear portal of entry, performing a colonoscopy might be useful to treat potential portals of entry of a new bacteremia episode, as patients with 1 IE episode are at higher risk of a new episode with higher associated mortality.10

In our study, colonoscopy was able to identify a presumed origin in 64% of patients without a clear origin, with most of the colonic findings being treatable. In addition, not only patients with an unknown presumed source of infection had relevant endoscopic findings. Forty-four percent of patients with a known origin had endoscopic findings, including patients for whom the presumed source of infection was the urinary tract. Unfortunately, we did not identify characteristics that differentiate these patients with endoscopic findings. Although patients without endoscopic findings could be expected to be younger, we identified no differences in age between the 2 groups. Likewise, the positivity of urinary cultures was not associated with the absence of endoscopic findings. Finally, as patients with colorectal disease, particularly neoplastic disease, might have microscopic gastrointestinal bleeding with subsequent anemia, we analyzed whether patients with colorectal findings had lower levels of hemoglobin, ferritin or transferrin saturation; however, we found no differences.

In our series, there were 80% of men with a median age of 76 years, and it is known that men are at higher age-specific risk for advanced colorectal neoplasm than women25; thus, we might suggest that we potentially found the expected number and type of findings in this population. However, a previous screening study of colonic disease performed in Austria in 3098 men aged between 70 and 79 years reported that the prevalence of adenomas was 31.7% and that of advanced adenomas was 10.7%.9 In our series, 23.1% of patients had advanced adenomas (P <.001). Although our study cannot prove causality, the prevalence of colorectal disease in EIEF is high. These findings are in consonance with those of Pericàs et al.13 However, although we found that the prevalence of colorectal neoplasms is higher than 50% in patients with EFIE with an unclear focus of infection, we also found that patients with nongastrointestinal sources of infection benefited from a colonoscopy as 44% had relevant endoscopic findings.

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. The main limitations are its retrospective nature and the sample size, inherent in EFIE as it is a serious but rare disease. The source of infection is typically presumed; however, it is very difficult to determine the exact moment in which bacteremia occurs. Although patients with EFIE were included from the moment that a colonoscopy was systematically performed in each participating center, colonoscopy was not performed in all EFIE cases, mainly due to the patient's rapid transfer to another center after surgery was refused or due to comorbidities or poor patient clinical course. Moreover, some colorectal lesions could have gone unnoticed due to inadequate bowel preparation. On the other hand, we compared the percentage of adenomas found in our cohort characterized mainly by men in their late seventies with a noncontemporaneous cohort of patients from a different country undergoing colonoscopy as colorectal screening,9 which can lead to a bias given that some patients in our cohort had previous colorectal disease, and some had symptoms attributable to the gastrointestinal tract. In this regard, due to the retrospective design of the study, we have no information regarding specific risk factors for colon cancer in our cohort.

CONCLUSIONSIn conclusion, although to date the recent American and European guidelines recommend colonoscopy only in patients with S. gallolyticus bacteremia or IE to determine whether malignancy or other mucosal lesions are present,16,26 colonic disease is also very common in E. faecalis endocarditis, even in patients with a presumed known portal of entry. Consequently, performing a colonoscopy in all EFIE patients, irrespective of the presumed source of infection, could be helpful to avoid a new bacteremia episode (and eventually IE) due to the same or a different microorganism.

FundingThis research did not receive a specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

ConflictS of interestAll authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

- -

Enterococcus faecalis is the third cause of IE, which mainly affects old patients with comorbidities, a population with a higher incidence of colorectal disease.

- -

Five percent of patients with IE will have an additional episode of IE with a higher mortality risk, and therefore identifying the portal of entry and treating it are important to lower the risk of a new IE episode.

- -

A recent retrospective study showed that patients with EFIE of unknown origin had a higher prevalence of colorectal lesions (31 of 61, 50.8%) than those with EFIE with a known origin (1 of 6, 16.7%); however, colonoscopy was not systematically performed in all patients, particularly not in those with a known origin.

- -

Colonic disease is very common in E. faecalis endocarditis, even in patients with a presumed known portal of entry.

- -

Sixty percent of E. faecalis endocarditis patients undergoing a colonoscopy had endoscopic findings indicating a potential source of bacteremia. Of these patients, 83% had neoplastic colorectal disease.

- -

In the subgroup of patients with a presumed known source of infection, colonoscopy indicated colorectal disease in 44%.

- -

Performing a colonoscopy in all EFIE patients, irrespective of the presumed source of infection, could help to avoid a new bacteremia episode by the same or a different microorganism.

L. Escolà-Vergé has a Río Hortega contract in the call 2018 Strategic Action Health from Instituto de Salud Carlos III of Spanish Health Ministry for 2019 to 2020.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2019.07.007.