Has been performed of the prognostic value of coronary physiological indices in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) after coronary revascularization deferral.

MethodsWe analyzed 714 patients (235 with DM) with deferred revascularization according to fractional flow reserve (> 0.80). A comprehensive physiological evaluation including coronary flow reserve (CFR), index of microcirculatory resistance, and fractional flow reserve was performed at the time of revascularization deferral. The median values of the CFR (2.88), fractional flow reserve (0.88), and index of microcirculatory resistance (17.85) were used to classify patients into high- or low-index groups. The primary outcome was the patient-oriented composite outcome (POCO) at 5 years, comprising all-cause death, any myocardial infarction, and any revascularization.

ResultsCompared with the non-DM population, the DM population showed higher risk of POCO (HR, 2.49; 95%CI, 1.64-3.78; P<.001). In the DM population, the low-CFR group had a higher risk of POCO than the high-CFR group (HR, 3.22; 95%CI, 1.74-5.97; P <.001). In contrast, CFR values could not differentiate the risk of POCO in the non-DM population. There was a significant interaction between CFR and the presence of DM regarding the risk of POCO (P for interaction=.025). Independent predictors of POCO were a low CFR and family history of coronary artery disease in the DM population and percent diameter stenosis and multivessel disease in the non-DM population.

ConclusionsThe association between coronary physiological indices and clinical outcomes differs according to the presence of DM. In deferred patients, CFR is the most important prognostic factor in patients with DM, but not in those without DM.

Keywords

The presence of myocardial ischemia is the most important prognostic factor in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).1 Current guidelines recommend that ischemia-causing coronary lesions be identified using fractional flow reserve (FFR) or instantaneous wave-free ratio measurement as standard invasive methods.1 However, patients still experience adverse cardiovascular events even after deferral of revascularization according to FFR, potentially due to the presence of a microvascular dysfunction that may cause ischemia or foster the progression of obstructive disease.2,3 Awareness of the existence of concealed mechanisms of coronary dysfunction might lead to closer patient surveillance and to specific treatments that might eventually improve patient outcomes.3 Therefore, the identification of patients at higher risk of future adverse cardiovascular events is a clinically important issue, even after a physiological assessment-guided revascularization strategy.

The presence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is strongly associated with CAD and increases the risk of cardiovascular events.4,5 Previous studies demonstrated that patients with DM were more likely to have multivessel disease and diffuse disease in small vessels6,7 and were associated with plaque vulnerability with a more significant atherosclerotic burden with lipid-rich plaques.8 In addition, microvascular dysfunction, which is more frequently observed in patients with DM,9,10 is a major determinant of the long-term outcome in this patient population.11 Therefore, coronary physiology in deferred coronary lesions might be different and have a different prognostic value in the DM population. Accordingly, we sought to investigate the prognostic implications of coronary physiological indices in the DM population.

MethodsStudy populationThe study population was derived from the International Collaboration of Comprehensive Physiologic Assessment Registry, which includes patient-level data from 3 prospective registries from 5 university hospitals in Korea, Tsuchiura Kyodo General Hospital in Ibaraki, Japan, and Hospital Clinico San Carlos in Madrid, Spain.3,12–15 All enrolled patients underwent comprehensive coronary physiological evaluations (FFR, coronary flow reserve [CFR], and index of microcirculatory resistance [IMR]) during coronary angiography, and all registries had the same exclusion criteria. FFR was measured in intermediate stenoses to determine the hemodynamic significance and CFR and IMR were measured as part of routine clinical practice and for research purposes. Exclusion criteria were hemodynamic instability, left ventricular dysfunction, and a culprit lesion of acute coronary syndrome.

The International Collaboration of Comprehensive Physiologic Assessment Registry included 1397 patients with 1694 vessels. According to the purpose of this study, this analysis included 714 patients with 988 vessels with deferred coronary revascularization according to FFR (> 0.80). In patients with multivessel interrogations, a representative vessel was defined as the one with the lowest FFR value. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at each participating center and was conducted according to the principals of the Declaration of Helsinki. All included centers are listed in . All patients provided written informed consent. The study protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03690713).

Invasive coronary angiography and measurement of physiological indicesInvasive coronary angiography was performed using standard techniques. Briefly, all angiograms were acquired after administration of intracoronary nitrate (100 or 200μg). Quantitative coronary analysis (QCA) was performed at each core laboratory of the included registries using a validated software program. Reference vessel diameter, minimal lumen diameter, percent diameter stenosis, and lesion length were evaluated. Coronary physiological indices were measured following diagnostic angiography.12 After engagement of a guide catheter, a pressure/temperature sensor-tipped guide wire (Abbott Vascular, United States) was calibrated and equalized to aortic pressure. It was then positioned at the distal part of a coronary artery. The FFR was acquired during maximal hyperemia and was defined as the lowest value of the mean hyperemic distal coronary to aortic pressure. CFR was calculated as the ratio of the resting mean transit time (Tmn) to the hyperemic Tmn. To obtain the Tmn, 3 injections of room-temperature saline were administered, and thermodilution curves were acquired in both resting and hyperemic states. The hyperemic state was induced with administration of intravenous adenosine (140μg/kg/min). Pressure wire pull-back was performed after every measurement to check for the presence of pressure drift. The IMR was calculated as distal coronary artery pressure×Tmn during hyperemia, and all IMR values were adjusted to the expected collateral support using Yong's formula (Pa×Tmn×([1.35×Pd/Pa] − 0.32).16

Data collection, clinical outcomes, and patient classificationData were collected using a standardized spreadsheet with standardized definitions of variables. This form was used to record clinical, angiographic, and physiological data on the enrolled patients at the time of the index procedure. Clinical outcome data were collected by outpatient clinic visits or telephone call. Baseline characteristics were obtained, including age, sex, body mass index, conventional risk factors (including hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, current smoking, prior history of myocardial infarction and revascularization, and family history of CAD), left ventricular ejection fraction (%), and presence of multivessel disease. Body mass index was defined as weight (kg)/height (m2). Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure exceeding 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure exceeding 90 mmHg, previous history of hypertension, or the use of antihypertensive medication. DM was defined as fasting glucose exceeding 126 mg/dL, previous history of DM, or the use of DM medication. Dyslipidemia was defined as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol exceeding 160 mg/dL, previous history of dyslipidemia, or the use of lipid-lowering medication. Patients were considered to be current smokers if they had smoked regularly within the past 12 months. Left ventricular ejection fraction was measured by M-mode echocardiographic estimation to evaluate systolic function and multivessel disease was defined as the presence of at least 2 major epicardial coronary arteries with greater than 50% luminal narrowing. All data were requested by the principal investigators of each registry to be sent to Seoul National University Hospital, Korea. All submitted data were double-checked by a central monitoring team at this hospital.

The primary outcome was the patient-oriented composite outcome (POCO) at 5 years, which comprised all-cause death, any myocardial infarction, and any revascularization. All clinical outcomes adhered to the definitions of the Academic Research Consortium, including the addendum to the definition of myocardial infarction.17,18

All patients were grouped according to CFR, FFR, and IMR values in a representative vessel. The median values of CFR (2.88), FFR (0.88), and IMR (17.85) were used to classify patients into high-or low-CFR, -FFR, and -IMR groups, respectively.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are described as number and relative frequency and continuous variables as mean and standard deviation. A t test was performed to compare continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to calculate the cumulative incidence of clinical outcomes, and a log-rank test was used to evaluate group differences. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). In addition, multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to identify independent predictors of POCO according to the presence of DM. The models included covariates that were considered clinically reliable or were associated with clinical outcomes (univariate analysis, P value <.1). To evaluate the relative importance of covariates in POCO prediction, information gains of variables were calculated with the 5000 permutation resampling method. Information gain presents the effect of a variable of interest and is defined as the change in information entropy between before and after the addition of the given variable.19 Entropy is a measure of the randomness of the distribution of data. Higher information gain means that the covariate provides more information for classifying the clinical outcome. In addition, the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) regression line was used to explore the prognostic value of CFR. All P values were 2-sided, and P <.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical package R version 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for statistical analysis.

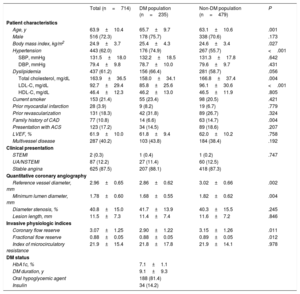

ResultsPatient characteristicsOf the 714 patients included in this study, 235 (32.9%) had DM. Baseline patient and lesion characteristics are presented in table 1. Compared with patients without DM, DM patients were older (63.1±10.6 vs 65.7±9.7 years; P=.001) and had a higher body mass index (24.6±3.4 vs 25.4±4.3; P=.027) and higher prevalence of hypertension (55.7% vs 74.9%; P <.001). Neither the clinical presentation nor the presence of multivessel disease were significantly different between the DM and non-DM populations.

Baseline characteristics

| Total (n=714) | DM population (n=235) | Non-DM population (n=479) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | 63.9±10.4 | 65.7±9.7 | 63.1±10.6 | .001 |

| Male | 516 (72.3) | 178 (75.7) | 338 (70.6) | .173 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.9±3.7 | 25.4±4.3 | 24.6±3.4 | .027 |

| Hypertension | 443 (62.0) | 176 (74.9) | 267 (55.7) | <.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 131.5±18.0 | 132.2±18.5 | 131.3±17.8 | .642 |

| DBP, mmHg | 79.4±9.8 | 78.7±10.0 | 79.6±9.7 | .431 |

| Dyslipidemia | 437 (61.2) | 156 (66.4) | 281 (58.7) | .056 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 163.9±36.5 | 158.0±34.1 | 166.8±37.4 | .004 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 92.7±29.4 | 85.8±25.6 | 96.1±30.6 | <.001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 46.4±12.3 | 46.2±13.0 | 46.5±11.9 | .805 |

| Current smoker | 153 (21.4) | 55 (23.4) | 98 (20.5) | .421 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 28 (3.9) | 9 (8.2) | 19 (6.7) | .779 |

| Prior revascularization | 131 (18.3) | 42 (31.8) | 89 (26.7) | .324 |

| Family history of CAD | 77 (10.8) | 14 (6.6) | 63 (14.7) | .004 |

| Presentation with ACS | 123 (17.2) | 34 (14.5) | 89 (18.6) | .207 |

| LVEF, % | 61.9±10.0 | 61.8±9.4 | 62.0±10.2 | .758 |

| Multivessel disease | 287 (40.2) | 103 (43.8) | 184 (38.4) | .192 |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| STEMI | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | .747 |

| UA/NSTEMI | 87 (12.2) | 27 (11.4) | 60 (12.5) | |

| Stable angina | 625 (87.5) | 207 (88.1) | 418 (87.3) | |

| Quantitative coronary angiography | ||||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 2.96±0.65 | 2.86±0.62 | 3.02±0.66 | .002 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 1.78±0.60 | 1.68±0.55 | 1.82±0.62 | .004 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 40.8±15.0 | 41.7±13.9 | 40.3±15.5 | .245 |

| Lesion length, mm | 11.5±7.3 | 11.4±7.4 | 11.6±7.2 | .846 |

| Invasive physiologic indices | ||||

| Coronary flow reserve | 3.07±1.25 | 2.90±1.22 | 3.15±1.26 | .011 |

| Fractional flow reserve | 0.88±0.05 | 0.88±0.05 | 0.89±0.05 | .012 |

| Index of microcirculatory resistance | 21.9±15.4 | 21.8±17.8 | 21.9±14.1 | .978 |

| DM status | ||||

| HbA1c, % | 7.1±1.1 | |||

| DM duration, y | 9.1±9.3 | |||

| Oral hypoglycemic agent | 188 (81.4) | |||

| Insulin | 34 (14.2) | |||

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CAD, coronary artery disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

All values are presented as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

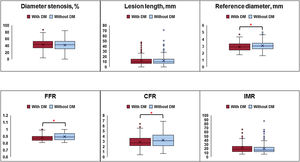

Anatomical lesion severity was not different between patients with and without DM (percent diameter stenosis, 41.7%±13.9% vs 40.3%±15.5%; P=.245; lesion length, 11.4±7.4mm vs 11.6±7.2mm; P=.846). However, the vessel reference diameter was smaller in patients with DM than in those without DM (2.86±0.62mm vs 3.02±0.66mm; P=.002) (figure 1 and table 1). In terms of physiological indices, patients with DM showed lower CFR and FFR values than those without DM (CFR, 2.90±1.22 vs 3.15±1.26; P=.011; FFR, 0.88±0.05 vs 0.89±0.05; P=.012) (figure 1 and table 1). There was no significant difference in IMR between patients with and without DM (21.8±17.8 vs 21.9±14.1; P=.978) (figure 1 and table 1).

Angiographic and physiological characteristics according to the presence of DM. Angiographic lesion severity, described by percent diameter stenosis and lesion length, was not significantly different between patients with and without DM. Regarding coronary physiological indices, CFR and FFR values were lower in patients with DM than in those without DM. Each box ranges from the upper to lower quartiles of the parameters and the line and x inside the box indicate the locations of the median and mean values. The whiskers extend from the box to the upper (upper quartile + 1.5×IQR) and lower (lower quartile − 1.5×IQR) extremes and outliers are plotted as individual dots. The red asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference using the Student t test. CFR, coronary flow reserve; DM, diabetes mellitus; FFR, fractional flow reserve; IMR, index of microcirculatory index; IQR, interquartile range.

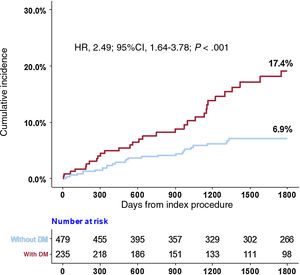

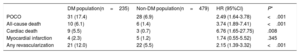

Compared with the non-DM population, the DM population showed a higher risk of POCO at 5 years (6.9% vs 17.4%; HR, 2.49; 95%CI, 1.64-3.78; P <.001) (figure 2 and table 2). Higher risk of POCO in the DM population was mainly driven by higher risk of all-cause death (6.1% for patients with DM vs 1.4% for patients without DM; HR, 3.74; 95%CI, 1.89-7.41; P <.001) and any revascularization (12.0% for patients with DM vs 5.5% for patients without DM; HR, 2.15; 95%CI, 1.39-3.32; P <.001) (table 2).

Clinical outcomes according to the presence of diabetes mellitus

| DM population(n=235) | Non-DM population(n=479) | HR (95%CI) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCO | 31 (17.4) | 28 (6.9) | 2.49 (1.64-3.78) | <.001 |

| All-cause death | 10 (6.1) | 6 (1.4) | 3.74 (1.89-7.41) | <.001 |

| Cardiac death | 9 (5.5) | 3 (0.7) | 6.76 (1.65-27.75) | .008 |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (2.3) | 5 (1.2) | 1.74 (0.55-5.52) | .345 |

| Any revascularization | 21 (12.0) | 22 (5.5) | 2.15 (1.39-3.32) | <.001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; DM, diabetes mellitus, HR, hazard ratio; POCO, patient-oriented composite outcome.

All values are presented as No. (%).

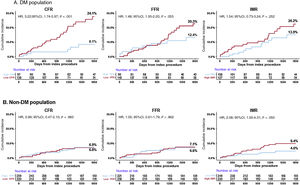

The relationship between physiological indices and long-term patient outcomes differed significantly between patients with and without DM. In the DM population, the low-CFR group had a higher risk of POCO than the high-CFR group (24.1% vs 8.1%; HR, 3.22; 95%CI, 1.74-5.97; P <.001) (figure 3 and table 3). In contrast, low FFR or high IMR values showed only a trend toward higher risk of POCO (low- vs high-FFR groups, 20.3% vs 12.4%; HR, 1.48; 95%CI, 1.00-2.20; P=.053; high- vs low-IMR groups, 20.2% vs 13.9%; HR, 1.54; 95%CI, 0.73-3.24; P=.252).

Cumulative incidence of the patient-oriented composite outcome according to physiological indices and the presence of DM. Differences are presented in the impact of coronary physiological indices on the patient-oriented composite outcome according to the presence of DM. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CFR, coronary flow reserve; DM, diabetes mellitusv; FFR, fractional flow reserve; HR, hazard ratio; IMR, index of microcirculatory resistance.

Clinical outcomes according to coronary physiological indices

| DM population (n=235) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low CFR | High CFR | HR (95%CI) | P* | |

| POCO | 25 (24.1) | 6 (8.1) | 3.22 (1.74-5.97) | <.001 |

| All-cause death | 9 (10.1) | 1 (1.1) | 7.05 (1.22-40.93) | .030 |

| Cardiac death | 8 (9.0) | 1 (1.1) | 6.26 (0.85-46.30) | .073 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (2.4) | 1 (2.0) | 2.22 (0.53-9.27) | .274 |

| Any revascularization | 16 (15.6) | 5 (7.1) | 2.46 (0.72-8.37) | .151 |

| Low FFR | High FFR | HR (95%CI) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCO | 22 (20.3) | 9 (12.4) | 1.48 (1.00-2.20) | .053 |

| All-cause death | 6 (6.1) | 4 (6.1) | 0.91 (0.32-2.55) | .855 |

| Cardiac death | 5 (5.1) | 4 (6.1) | 0.76 (0.30-1.93) | .566 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (3.0) | 1 (1.2) | 1.83 (0.18-18.64) | .612 |

| Any revascularization | 16 (15.6) | 5 (7.1) | 1.94 (0.97-3.90) | .063 |

| High IMR | Low IMR | HR (95%CI) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCO | 20 (20.2) | 11 (13.9) | 1.54 (0.73-3.24) | .252 |

| All-cause death | 6 (6.1) | 4 (6.2) | 1.26 (0.39-4.12) | .698 |

| Cardiac death | 5 (4.9) | 4 (6.2) | 1.05 (0.38-2.92) | .921 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (3.2) | 1 (1.2) | 0.56 (0.42-15.73) | .310 |

| Any revascularization | 14 (15.0) | 7 (8.2) | 1.70 (0.86-3.37) | .126 |

| Non-DM population (n=476) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low CFR | High CFR | HR (95%CI) | P* | |

| POCO | 13 (6.8) | 15 (6.9) | 0.99 (0.47-2.10) | .983 |

| All-cause death | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | 1.14 (0.19-6.72) | .884 |

| Cardiac death | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 2.28 (0.12-43.11) | .582 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.3) | 0.75 (0.19-2.94) | .685 |

| Any revascularization | 10 (5.4) | 12 (5.6) | 0.95 (0.48-1.90) | .894 |

| Low FFR | High FFR | HR (95%CI) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCO | 15 (7.1) | 13 (6.6) | 1.05 (0.61-1.79) | .862 |

| All-cause death | 2 (1.0) | 4 (1.9) | 0.45 (0.11-1.75) | .248 |

| Cardiac death | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.4) | NA | NA |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.59 (0.48-7.36) | .685 |

| Any revascularization | 13 (6.2) | 9 (4.8) | 1.32 (0.96-1.81) | .087 |

| High IMR | Low IMR | HR (95%CI) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCO | 18 (9.4) | 10 (4.6) | 2.08 (1.00-4.31) | .050 |

| All-cause death | 4 (2.1) | 2 (0.9) | 2.26 (0.53-9.66) | .274 |

| Cardiac death | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 2.23 (0.17-29.51) | .543 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (1.5) | 2 (0.9) | 1.68 (0.60-4.74) | .325 |

| Any revascularization | 14 (7.5) | 8 (3.8) | 2.03 (0.67-6.18) | .213 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CFR, coronary flow reserve; DM, diabetes mellitus; FFR, fractional flow reserve; HR, hazard ratio; IMR, index of microcirculatory resistance; NA, not available; POCO, patient-oriented composite outcome.

All values are presented as No. (%).

In the non-DM population, CFR and FFR values could not differentiate the risk of POCO. The low-CFR and low-FFR groups showed comparable risk of POCO at 5 years to the high-CFR and high-FFR groups (low- vs high-CFR groups, 6.8% vs 6.9%; HR, 0.99; 95%CI, 0.47-2.10; P=.983; low- vs high-FFR groups, 7.1% vs 6.6%; HR, 1.05; 95%CI, 0.61-1.79; P=.862) (figure 3 and table 3). IMR showed a borderline association with risk of POCO in the non-DM population (HR, 2.08; 95%CI, 1.00-4.31; P=.050) (figure 3 and table 3).

When the CFR values were treated as a continuous variable, the 5-year risk of POCO was significantly increased with a decrease in CFR in the DM population (HR, 1.71; 95%CI, 1.39-2.11; P <.001), but not in the non-DM population (HR, 1.13; 95%CI, 0.85-1.50; P=.418) (). There were no significant interactions of FFR or IMR values with the presence of DM for POCO (P for interaction=.353 for FFR and .163 for IMR vs DM). However, there was a significant interaction between CFR values and the presence of DM (P for interaction=.025).

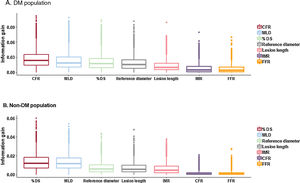

Independent predictors and information gain for clinical outcomesIndependent predictors of POCO at 5 years in patients with DM were a low CFR and family history of CAD (table 4). Of the angiographic and physiological indices, CFR showed the highest information gain (0.027; 95%CI, 0.010-0.044) (figure 4). In contrast, percent diameter stenosis and multivessel disease were independent predictors of POCO at 5 years in patients without DM (table 4) and diameter stenosis (0.014; 95%CI, 0.006-0.022) showed the highest information gain (figure 4).

Independent predictors of the patient-oriented composite outcome according to the presence of DM

| DM population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P |

| Low CFR* | 3.49 (1.01-11.78) | .048 |

| Family history of CAD | 8.23 (3.21-21.11) | <.001 |

| Non-DM population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P |

| % diameter stenosis | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) | .047 |

| Multivessel disease | 1.65 (1.01-2.69) | .026 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CAD, coronary artery disease; CFR, coronary flow reserve; DM, diabetes mellitus; HR, hazard ratio.

The following risk factors were included in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model: age, sex, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, family history of CAD, previous myocardial infarction, previous revascularization, ejection fraction, clinical presentation, disease extent, lesion characteristics (lesion length, diameter stenosis, minimum lumen diameter, reference vessel diameter), and physiologic characteristics.

Information gains of angiographic and physiological indices. Of angiographic and physiological indices, the highest information gain for POCO at 5 years was seen with CFR in the DM population and with diameter stenosis in the non-DM population. Each box ranges from the upper to lower quartiles, and the line inside the box indicates the location of the median. The whiskers extend from the box to the upper (upper quartile + 1.5×IQR) and lower (lower quartile − 1.5 x IQR) extremes and outliers are plotted as individual dots. CFR, coronary flow reserve; DM, diabetes mellitus; DS, diameter stenosis; FFR, fractional flow reserve; IMR, index of microcirculatory index; IQR, interquartile range; MLD, minimal lumen diameter.

This study investigated the prognostic implications of invasive physiological indices in deferred patients with DM. The main findings were as follows: first, among patients with deferred revascularization based on FFR, the DM population had a higher risk of POCO at 5 years than the non-DM population; second, a low CFR value was associated with a higher risk of POCO at 5 years and was an independent predictor of POCO in the DM population but not in the non-DM population; and third, there were no significant interactions of FFR and IMR values with the presence of DM regarding the risk of POCO. However, there was a significant interaction between CFR and the presence of DM. These results indicate the existence of different pathophysiological mechanisms in the genesis of POCO in patients with and without DM when coronary revascularization is deferred on the basis of FFR.

Association between coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitusDM is an important risk factor for CAD, and its prevalence is rapidly growing worldwide.4,5 Patients with DM are more likely to have severe and diffuse vascular disease, multivessel disease, and microvascular dysfunction,7,9,10 which are poor prognostic factors in patients with CAD. The current guidelines recommend invasive physiological index-guided coronary revascularization in patients without evidence of ischemia, with no differences in the indications for revascularization between DM and non-DM populations.1 However, the coronary physiological and prognostic implications of physiological indices can be different in the DM population because DM affects various compartments of the coronary circulation system.4 The long-term prognosis of patients with DM without obstructive coronary disease but impaired CFR is poor and similar to that of patients with DM and obstructive CAD.11 In this context, the current study evaluated the characteristics and prognosis of deferred coronary lesions in the DM population, taking into account not only the functional relevance of epicardial coronary stenoses, but also the subtended microcirculatory status.

Angiographic and physiological features in deferred patients with diabetes mellitusThe current study focused on coronary lesions deferred according to a FFR> 0.80 and investigated the impact of DM on deferred coronary lesions. The study results showed that angiographic lesion severity, assessed by percent diameter stenosis and lesion length, did not differ between patients with and without DM. However, reference diameter and minimal lumen diameter were smaller in patients with DM than in patients without DM. These results imply that there is a possibility of diffuse epicardial coronary disease in patients with DM, suggesting that deferred patients with DM might have a more extensive disease burden than those without DM. These results are in line with previous work indicating that the presence of DM is associated with more severe and diffuse CAD.7 In terms of physiological assessments, CFR and FFR values were lower in DM patients. These angiographic and physiological features seem to be the main factors underlying the higher risk of POCO in deferred coronary lesions in DM patients than in those without DM. In the current study, deferred patients with DM showed about a 2.5-fold higher risk of POCO than those without DM, even though all patients had a FFR> 0.8.

Given the potential impact of DM on the coronary microvascular system, it is interesting that the IMR values were similar in the DM and non-DM patients in our study. Although IMR reflects the microvascular state during hyperemia,20 not all aspects of microvascular dysfunction can be assessed by this index.21 The direct relationship between DM and IMR has been sparsely studied in a small number of patients.22 In addition, several previous studies reported that DM was not an independent predictor of high IMR, with DM patients showing a comparable level of IMR to non-DM patients.3,23 The microvascular dysfunction in DM has been explained by an endothelial dysfunction in which the coronary flow cannot be increased when needed.10,11,21 In this regard, our study results suggest that CFR can be a more appropriate index for evaluating microvascular dysfunction in patients with DM.

Clinical implications of physiological indices for revascularization deferral in patients with diabetes mellitusAlthough patients with DM generally have a higher risk of cardiovascular events than those without the condition, the risk is reported to differ according to anatomical and physiological disease burden. Malik et al.24 reported that the annual risk of a CAD event ranged from 0.4% to 4% per year, according to the amount of coronary artery calcium. Murthy et al.11 investigated coronary vascular dysfunction in the DM population and reported that DM individuals without CAD and preserved CFR had a very low risk of cardiac death. These studies suggest that DM is associated with a heterogeneous risk of CAD, thereby supporting the need for additional risk stratification in the DM population.

The current study demonstrated that CFR was the most important prognostic factor in the DM population after deferral of revascularization according to FFR. CFR showed the highest information gain and was an independent predictor of 5-year POCO in the DM population. There was a significant interaction of CFR values with the presence of DM regarding the risk of POCO, but not of FFR or IMR. Given that DM affects various compartments of the coronary circulation system, it may be natural that CFR is better associated with patients’ outcomes than the other specific indices.4 CFR reflects the status of both macrovascular and microvascular compartments of coronary circulation and its capacity to respond to oxygen demand. Compared with the DM population, associations of coronary physiological indices with future clinical outcomes and prognostic factors were different in the non-DM population. Our study results suggest that the association between coronary physiological indices and clinical outcomes in deferred patients according to FFR can differ according to the presence of DM, thereby supporting the importance of CFR measurement in DM patients.

Future perspectiveThe implications of these findings merit further research designed to improve the safety of revascularization-related decision-making and, ultimately, to obtain better long-term clinical outcomes in patients with DM. On the one hand, the presence of a normal CFR in vessels with a FFR> 0.80 in patients with DM might support deferral of revascularization. On the other hand, abnormal CFR values might foster implementation of tighter measures to control DM and cardiovascular risk factors. In the absence of studies supporting specific treatment for abnormal microcirculatory function in the DM population to modify prognosis, an abnormal CFR might indicate the presence of higher cardiovascular risk and therefore the need for closer patient surveillance. In addition, considering the diverse nature of microvascular dysfunctions, our study raises the need for thorough physiological evaluations in other disease states, such as CAD with primary myocardial disease, to understand the state of microvascular circulation.

LimitationsThere are several limitations to be considered. First, this study was not a randomized controlled trial and could not control for all potential biases and confounding factors. Therefore, further work is needed to validate our results. Second, information on the true anatomical disease burden is not available because intravascular imaging was not performed. Third, although the same exclusion criteria were applied, there might be some heterogeneity in the patient population because this study comprised 3 separate registries.

CONCLUSIONSThe association between coronary physiological indices and clinical outcomes in patients with CAD differs according to the presence of DM. CFR is the most important prognostic factor in patients with DM, but not in those without DM. Our results suggest that the pathophysiological mechanisms influencing long-term outcomes after coronary revascularization deferral might be different in patients with and without DM.

- -

DM is an important risk factor for CAD that affects various compartments of the coronary circulation system.

- -

However, the role of comprehensive coronary physiological assessment in CAD patients with DM has not been thoroughly investigated.

- -

This study demonstrated that the DM population with deferred coronary revascularization has a higher risk of POCO at 5 years than the non-DM population.

- -

Low CFR was associated with a higher risk of POCO and was an independent predictor of POCO in the DM population, but not in the non-DM population. There was a significant interaction between CFR values and the presence of DM regarding the risk of POCO.

- -

Our results suggest that the coronary physiology of the DM population is different from that of the non-DM population, thereby supporting the importance of CFR measurement in the DM population after deferral of revascularization.

B.-K. Koo received an Institutional Research Grant from St. Jude Medical (Abbott Vascular) and Philips Volcano. J. Myung Lee received a research grant from St. Jude Medical (Abbott Vascular) and Philips Volcano. J. Escaned received personal fees from Philips Volcano, Boston Scientific, and Abbott/St. Jude Medical outside the submitted work. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest relevant to the submitted work.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2020.06.007