To the Editor,

A 2-year-old male infant was admitted to the hospital with a history of rapid decline in general health and persistent hyperthermia (38.5°C to 39°C) over the previous 6 days. No history of congenital heart disease or previous hospitalization was reported by parents. General inspection revealed eutrophic child, easily irritable, and small pustular lesions over both legs. Rapid pulse (120bpm), dry and pale mucosa, and bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhagic spots were noted. Large erythematic area over the right hypochondrium, diffuse petechial exanthema over the lower limbs, and left proximal forefinger interphalangeal joint swelling were also observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A, left forefinger, proximal interphalangeal joint swelling. B, erythematic spot over the right hypochondrium and diffuse petechial exanthema over the right lower limbs. C, petechial exanthema over the right foot. D, subconjunctival hemorrhage spots.

Cardiac examination revealed hyperdynamic precordium and 3+/4+ systolic murmur was heard over the apex irradiating to the left axilla and posterior torso.

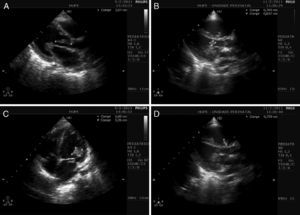

Laboratory findings on admission were white blood cell count 24500/μL with 25% rod-like neutrophil, platelet 21000/μL, hematocrit 24.7%, creatinine 0.4mg/dL, GGT 54IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 518IU/L, sodium 130mEq/L, and potassium 2.9mEq/L. Bidimensional color Doppler echocardiogram with parasternal short axis and apical long axis views showed left chambers enlargement (left ventricular diameter 37mm diastolic and 23mm systolic). A filamentary vegetation was observed extending from the ventricular aspect of the anterior mitral valve leaflet to the left ventricular outflow tract adherent to the noncoronary aortic cusp (Figure 2A and B; Movies 1 and 2). Severe mitral and mild aortic regurgitations were also present (Movie 3).

Figure 2. A, subaortic filament-shaped vegetation, extending from the anterior mitral valve leaflet to the noncoronary aortic cusp (marks). B, disc-shaped vegetation, attached to the anterior mitral valve leaflet (marks). C, large vegetation over the ventricular aspect of the anterior mitral valve leaflet and subvalve apparatus. Subaortic filamentary vegetation was no longer observed, and a tiny portion remained attached to the mitral valve (marks). D, disc-shaped vegetation, attached to the septal tricuspid valve leaflet (marks).

An acute infective endocarditis (IE) was thus considered and before starting an empiric antibiotic schedule (ceftriaxone, oxacillin, and vancomycin), two blood specimens were cultured. A surgical intervention was considered but disapproved by the cardiac team.

In 48h, metabolic acidosis, respiratory distress with sign of spontaneous bleeding from lung parenchyma, and anisocoria evolved. New echocardiogram showed that sub-aortic filamentary vegetation was no longer present and right ventricle was dilated. A new image adhered to the septal tricuspid valve leaflet was observed (Figure 2C and D; Movies 4 and 5). The child evolved with bilateral mydriasis, progressing to death.

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) was isolated from all blood samples, and was sensitive to vancomycin, clindamycin, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim and resistant to both oxacillin and penicillin.

Current report describes a case of aggressive IE caused by S. aureus involving 3 cardiac valves in an otherwise healthy male infant. In children, IE is commonly associated with congenital or rheumatic heart disease.1 In healthy children, bacteremia secondary to skin infection or due to central catheters invasion, particularly in neonates, is associated with IE, and S. aureus has been the most frequent infective agent isolated from blood cultures.1, 2 Community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) is a rapidly growing worldwide problem.3 Reassuringly, the prevalence of CA-MRSA colonization in a community's young children remains very low4. Milstone et al. reported a 61% CA-MRSA prevalence among all MRSA-colonized children in a pediatric intensive care unit.5 Jaggi et al. reported that invasive CA-MRSA represented 12.7% of all MRSA strain isolated in pediatric ICU, but none related to IE.6 Children with CA-MRSA infections tended to be younger African-American descendents and admitted to the hospital 1 week after initial infection.5, 6 Markers of CA-MRSA are no hospitalization, no dialysis or surgery, no exposure to interventional procedures, and neither MRSA colonization nor confinement in care or performing centers in the previous year, and isolated S. aureus susceptible to a wide range of antibiotics, including sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim and clindamycin.3 Over 95% of CA-MRSA strains carry toxins-encoding genes (eg, Pantone-Valentine), predisposing to severe soft-tissue infections and necrotizing pneumonia.3

The history of no previous hospitalization, findings of diffuse petechial exanthema and abdominal spot, and isolation from blood cultures of MRSA sensitive to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim confirmed this rare case of CA-MRSA IE. The extensive vegetation affecting mitral, aortic, and tricuspid valves and the clinical signs of necrotizing pneumonia and severe systemic embolization are evidence of the virulent strain of the infective agent in this case.

No clear recommendation can be obtained from the current case, owing to the fatal outcome. Jaggi et al. successfully employed surgical interventions in CA-MRSA infections not associated with IE, with no deaths.6 High diagnostic suspicion and early surgical intervention in selected cases may be beneficial.

.

Appendix A. Supplementary MaterialSupplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.rec.2011.06.011.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataCorresponding author: ecgar@yahoo.com