Differences in the treatment of atrial fibrillation between men and women were investigated by using patients in a local health district as a reference population. The study included 688 patients (359 female) who presented with atrial fibrillation. Women were older, more frequently had heart failure, and were more often functionally dependent than men. With regards to the management of atrial fibrillation, women were prescribed digoxin more frequently than men, but underwent electrical cardioversion less often, were less frequently seen by a cardiologist, and understood less about their treatment. After stratifying the findings by age and adjusting for heart failure and the degree of functional dependence, it was observed that women aged over 85 years were prescribed digoxin more often than men, while women aged under 65 years underwent cardioversion less often than men. In conclusion, gender differences observed in the treatment of atrial fibrillation cannot be fully explained by differences in clinical characteristics between men and women in the population.

Keywords

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most prevalent arrhythmia and should be treated according to standard guidelines.1 Some studies have found differences between gender in how AF is treated, and have demonstrated that women receive more conservative treatment.2,3 Similar differences have also been described in the context of other cardiovascular diseases.4,5,6 However, all these studies have an inclusion bias depending on the origin of the patients, since they used criteria based on admission, level of care or the location of the referring specialist. The present study analyzes the treatment of AF in relation to gender in a group of patients from a local health district.

MethodsA cross-sectional, comparative, retrospective, single-center study was designed in the UFIB (Unitat Funcional i Integral de Braquiteràpia) del GIRAFA (Grup Integrat de Recerca en Fibril·lació Auricular, or Atrial Fibrillation Integrated Research Group). This group followed up patients at different care levels: a tertiary care hospital and two primary care centers dependent on the tertiary care hospital. Prospective follow-up was conducted during visits to the primary care physician and cardiologists, and in the hospital's emergency, internal medicine, neurology and cardiology units. One of the objectives of the group was to assess equality between gender regarding the allocation of resources. The present work was a substudy of patients included in previous studies according to a previously defined methodology7,8 with the aim of identifying gender differences in the treatment of AF, and thus this was the dependent variable.

Age, degree of dependency (Barthel index), hypertension, diabetes, heart disease and type, AF classification and associated complications at baseline were used as independent variables. The following were considered as independent variables in the treatment of AF: antiarrhythmic and prophylactic treatment of arterial embolism according to the clinical guidelines9,10,11; ablative treatment and non-pharmacological treatment; visits to the cardiologist during the course of AF; echocardiographic study and 24h Holter monitoring; and the patients’ level of understanding about diagnosis and treatment.

In the statistical analysis the mean and standard deviation were used for the continuous variables (analysis of variance) and absolute values or percentages for the discrete variables (χ2 test or Fisher's exact test). An age-stratified analysis was conducted, and logistic regression used to adjust the raw odds ratio (OR) of the statistically significant independent variables in the univariate study, as well as the adjusted OR for baseline factors whose distribution differed between sexes. A P-value of <.05 was used as a cutoff value for statistical significance.

ResultsA total of 668 patients were included (359 women and 309 men). The women were older (77.9±9.2 years vs 71±12.1 years; P<.001), with greater functional dependency (Barthel index, 87.6±19.1 vs 91.6±17.1; P=.006) and a higher prevalence of heart failure (35.9% vs 23.6%; P=.001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Basal Clinical Characteristics of the Study Patients *

| Total (n=668) | Women (n=359) | Men (n=309) | P | |

| Age (years) | 74.6±11.2 | 77.7±9.2 | 71±12.1 | <.001 |

| Patients (by age group) | <.001 | |||

| <65 years | 109 (16.3) | 31 (8.6) | 78 (25.2) | |

| 65–74 years | 180 (26.9) | 87 (24.2) | 93 (30) | |

| 75-84 years | 270 (40.4) | 158 (44) | 112 (36.2) | |

| ≥85 years | 109 (16.3) | 83 (23.1) | 26 (8.4) | |

| Time from diagnosis of AF (months) | 66.2±74.1 | 67.2±67.3 | 64.9±82.2 | NS |

| Barthel index score (n=620) | 89.4±18.3 | 87.6±19.1 | 91.6±17.1 | .006 |

| Barthel group (n=620) | .001 | |||

| ≥90 points | 471 (76) | 236 (71) | 235 (82) | |

| <90 points | 149 (24) | 97 (29) | 52 (18) | |

| Care level | NS | |||

| Family doctor | 286 (43) | 155 (43) | 131 (42) | |

| Cardiologist (outpatients) | 121 (18) | 58 (16) | 63 (20) | |

| Emergency unit | 169 (25) | 95 (26.5) | 74 (24) | |

| Hospital in-patient | 92 (14) | 51 (14.5) | 41 (13) | |

| Heart disease (n=654) | 344 (53) | 198 (56) | 146 (49) | NS |

| Hypertension (n=658) | 426 (65) | 237 (67) | 189 (62) | NS |

| Diabetes (n=657) | 152 (23) | 81 (23) | 71 (24) | NS |

| Type of AF (n=660) | NS | |||

| First episode | 49 (7) | 27 (8) | 22 (7) | |

| Paroxysmal | 207 (31) | 109 (31) | 98 (32) | |

| Persistent | 38 (6) | 15 (4) | 23 (7) | |

| Permanent | 366 (55) | 202 (57) | 164 (53) | |

| Complications (n=624) | ||||

| Stroke | 102 (16) | 62 (17) | 40 (13) | NS |

| Heart failure | 202 (32) | 129 (36) | 73 (24) | .001 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; NS, not significant.

* Data are expressed as n (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Regarding overall management (Table 2), the women received digoxin more often (58% vs 45%; P=.007), underwent fewer electrical cardioversion procedures (9% vs 16%; P=.005), were seen by a cardiologist less often (77% vs 88%; P<.001) and knew less about the treatment they received (51% vs 66%; P=.002).

Table 2. Comparison of Differences in Treatment Between Sexes a , *

| Total | Women | Men | P | |

| Antiarrhythmic treatment | 666 | 357 | 309 | NS |

| Without treatment | 165 (25) | 83 (23) | 82 (27) | |

| With treatment | 501 (75) | 274 (77) | 227 (73) | |

| Type of antiarrhythmic drug a | 501 | 274 | 227 | |

| Digoxin | 261 (52) | 158 (58) | 103 (45) | .007 |

| Amiodarone | 130 (26) | 70 (26) | 60 (26) | NS |

| Beta blockers | 76 (15) | 35 (13) | 41 (18) | NS |

| Calcium channel blockers | 65 (13) | 32 (12) | 33 (15) | NS |

| Class Ic agents | 45 (9) | 19 (7) | 26 (11) | NS |

| Suitable antiarrhythmic treatment | 643 | 342 | 301 | NS |

| Yes | 504 (78) | 274 (80) | 230 (76) | |

| No | 139 (22) | 68 (20) | 71 (24) | |

| Prophylaxis of thrombotic events | 657 | 350 | 307 | NS |

| No treatment | 105 (16) | 55 (16) | 50 (156) | |

| Some treatment | 552 (84) | 295 (84) | 257 (84) | |

| Type of prophylactic treatment | 549 | 291 | 259 | |

| Platelet aggregation inhibition | 198 (36) | 107 (37) | 91 (35) | NS |

| Anticoagulant therapy | 351 (64) | 183 (63) | 168 (65) | NS |

| Suitable prophylaxis of thrombotic events | 657 | 350 | 307 | NS |

| Yes | 499 (76) | 265 (76) | 234 (76) | |

| No | 158 (24) | 85 (24) | 73 (24) | |

| Electrical cardioversion | 638 | 335 | 303 | .005 |

| Yes | 77 (12) | 29 (9) | 48 (16) | |

| No | 561 (88) | 306 (91) | 255 (84) | |

| Attempted ablation | 668 | 359 | 309 | NS |

| Yes | 17 (2.5) | 5 (1.4) | 12 (3.9) | |

| No | 651 (97.5) | 354 (98.6) | 297 (96.1) | |

| Assessment by a cardiologist | 623 | 331 | 292 | <.001 |

| Yes | 513 (82) | 255 (77) | 258 (88) | |

| No | 110 (18) | 76 (23) | 34 (12) | |

| Echocardiographic study | 510 | 272 | 238 | NS |

| Yes | 399 (78) | 213 (78) | 186 (78) | |

| No | 111 (22) | 59 (22) | 52 (22) | |

| Holter monitoring | 610 | 322 | 288 | NS |

| Yes | 127 (21) | 61 (19) | 66 (23) | |

| No | 483 (79) | 261 (81) | 222 (77) | |

| Knowledge regarding the arrhythmia | 453 | 236 | 217 | NS |

| Yes | 366 (81) | 186 (79) | 180 (83) | |

| No | 87 (19) | 50 (21) | 37 (17) | |

| Knowledge regarding arrhythmia treatment | 376 | 198 | 178 | .002 |

| Yes | 218 (58) | 100 (51) | 118 (66) | |

| No | 158 (42) | 98 (49) | 60 (34) |

NS, not significant.

* Data are expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

a Some patients took more than one drug.

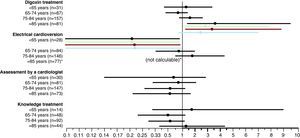

The clinical differences disappeared when the patients were stratified by age, except for women older than 85 years, who received digoxin more often, and women younger than 65 years, who underwent fewer electrical cardioversion procedures. The differences in these two age segments were maintained after adjusting for heart failure episodes or the Barthel index (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Age-stratified analysis. The raw odds ratio is shown for women vs men for the four significant variables in the univariate study. When the differences were statistically significant, the analysis was adjusted for heart failure (green), Barthel index (red) and for both (blue).

DiscussionThe present study provides evidence of differences between women and men in the treatment of AF in regard to four aspects: digoxin treatment; electrical cardioversion procedures; assessment by a cardiologist; and level of understanding of the treatment received. Thus, women received digoxin treatment more often, whereas men underwent electrical cardioversion procedures and cardiologist visits more often and had a better understanding of the procedure. These apparent differences are explained by the different demographic characteristics of the women and, in particular, their greater age. Furthermore, functional dependency and the prevalence of heart failure were greater in women. Even when these factors are taken into account, there was still a higher prevalence of digoxin treatment among women older than 85 years or more, and fewer electrical cardioversion procedures among women younger than 65 years. This was a population-based study and included all the potential sources of patients and care levels for these types of diseases: primary care, outpatient specialist clinics, emergency units, and in-hospital care. Using this approach, we attempted to avoid the bias inherent to previous studies2,3 caused by the non-inclusion of some of these sources. Thus, the differences found reliably reflect the differences in the population.

It is striking that women received more conservative treatment despite having greater comorbidities. In fact, they received digoxin to control the heart rate more often and had fewer indications for electrical cardioversion. Although the difference was not significant, perhaps due to the small number of cases, ablation of the arrhythmia was less frequent in women. Similar results have been found in European studies.12 This could be due to a longer delays in diagnosing women or in medical attention compared to men2,3,13 (greater age, longer evolution of the arrhythmia, greater atrial dilatation) and fewer women being referred to a cardiologist.14 In our study, this difference disappeared when the patients were stratified by age.

One of the limitations of the study is that differences in prognosis were not analyzed. In this regard, the results reported vary considerably,14,15 and thus the inclusion of this information would have been of interest. Furthermore, this was a substudy that was not specifically designed to analyze sex differences. Neither were the reasons for the initial visit that led to a diagnosis of arrhythmia analyzed, which would have helped in interpreting the differences found. Another limitation is the fact that this was a single-center study, and thus the findings cannot be extrapolated to the Spanish population as a whole without a prior study of external validity. Finally, for some variables, the number of events was low and thus some estimations could be unreliable. However, this interdisciplinary study has the advantage of reflecting actual practice at different care levels, without treatment biases attributable to the inclusion method. Thus, we conclude that although the differences at the population level in the clinical characteristics of the patients with AF can partly explain the differences found, certain inequalities are suspected which cannot be accounted for.

FundingDr. Òscar Miró has a research enhancement grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo [Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs]). This work was made possible in part by a grant from the Generalitat de Catalunya for consolidated research groups 2009–2013 (SGR 2009-1385).

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Received 10 March 2010

Accepted 27 April 2010

Corresponding author: Área de Urgencias, Hospital Clínic, Villarroel, 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain. bcvinent@clinic.ub.es