The Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) presents its annual activity report for 2021.

MethodsAll Spanish centers with catheterization laboratories were invited to participate. Data were collected online and were analyzed by an external company, together with the members of the ACI-SEC.

ResultsA total of 121 centers participated (83 public and 38 private). Compared to 2020, both diagnostic coronary angiograms and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) increased by 11,4% and 10,3%, respectively. The radial approach was the most used access (92,8%). Primary PCI also increased by 6.2% whereas rescue PCI (1,8%) and facilitated PCI (2,4%) were less frequently conducted. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation was one of the interventions with the most relevant increase. A total of 5720 transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedures were conducted with an increase of 34,9% compared to 2020 (120 per million in 2021 and 89,4 per million in 2020). Other structural interventions like transcatheter mitral or tricuspid repair, left atrial appendage occlusion and patent foramen oval closure also experienced a significant increase.

ConclusionsThe 2021 registry demonstrates a clear recovery of the activity both in coronary and structural interventions showing a relevant increase compared to 2020, the year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords

For more than 30 years, or, more specifically, since 1990, one of the main tasks of the Steering Committee of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) has been to report the activity recorded in interventional cardiology laboratories in Spain.1–30 These data are collected with considerable interest because they allow us to assess the changes over time in activity vs previous years, the incorporation and growth of new techniques, and the differences among Spanish regions.

Data collection is voluntary; nonetheless, due to the major impact of the national registry data, virtually all publicly-funded and private health centers contribute their data, which has become an annual tradition in all hospitals wishing to participate. Because the registry is not audited, it has several implicit limitations.30 The variables requested are modified annually based on the arrival of new techniques or devices. The database is managed by an independent external company that cleans the data before providing them to the Steering Community of the ACI-SEC. The registry data were presented at the ACI-SEC congress, celebrated on June 10, 2022, in Alicante.

Ultimately, the annual ACI-SEC registry is a testament to the engagement and transparency of the centers involved. It provides a series of vitally important data for describing the trends in interventional cardiology and comparing the data not only among Spanish autonomous communities, but also with those of other countries. This registry could be crucial for investment policies, by justifying the need for growth in certain techniques and in specific regions. In addition, the enormous amount of information gathered provides an opportunity to produce various scientific publications.

This article represents the 31st report on interventional activity in Spain and collects activity from public and private centers corresponding to 2021.

METHODSThe present registry reports diagnostic and therapeutic procedural activity undertaken in 2021 in interventional cardiology laboratories from most Spanish centers. The registry is voluntary and the data are not audited. In the case of anomalous data, the responsible center was contacted to minimize the margin of error. However, because the registry comprises individual reports from each center, it has an implicit margin of error. Data collection was performed using an electronic form that is modified annually by the members of the ACI-SEC Steering Committee to adapt the variables to new techniques and procedures.31 Nonetheless, the forms may omit a variable related to a new device or procedure. The data were analyzed by an external company with the help of one of the members of the committee. The members of the Steering Committee of the ACI-SEC were in charge of reporting the activity data for 2021 and comparing them with those of previous years.

As in previous years, the population-based calculations for both Spain and each autonomous community were based on the data published by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics on its website.32 The Spanish population was considered to have increased to 47 385 107 individuals; this total population figure was used for calculations per million population. Absolute (No.) and relative (%) data are reported.

RESULTSInfrastructure and resourcesIn 2021, 121 of the 122 invited centers participated (99.1%). All of the 83 publicly-funded health centers submitted their data (100%), whereas 38 of the 39 private centers invited provided data (97.4%). These numbers indicate no change in the participation of publicly-funded health centers vs 2020 but a reduction in 2 private centers. A total of 265 catheterization laboratories were recorded; of these, 153 (57.7%) were exclusively for cardiac catheterization, 70 (26.4%) were shared, 29 (10.9%) were hybrid, and 13 (4.9%) were supervised.

Reported staff grew to 494 interventional cardiologists, of which 474 (95.9%) were accredited by the ACI-SEC. The proportion of female interventional cardiologists (24.4%) slightly increased vs previous years (23.7% in 2019 and 23.9% in 2020). In addition, the numbers of registered nurses (722) and radiology technicians (106) were similar to those of previous years.

Diagnostic activity/coronary interventionsDiagnostic activityAfter registering a decrease in diagnostic procedures in 2020 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic,29 interventional diagnostic activity in Spain increased in 2021 by 11.4% (157 994 vs 147 478 in 2020), and the numbers were very similar to those of 2019 (165 124). Of these procedures, the vast majority were coronary angiograms (93%), followed by right heart catheterizations (4.6%) and endomyocardial biopsies (1.2%).

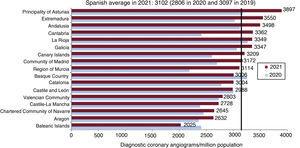

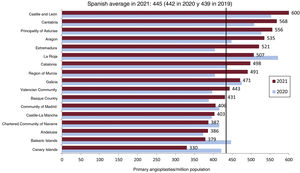

As in previous years, the predominant access route was radial (92% of studies). The national average of coronary angiograms recovered to 3102 per million population; the greatest increases vs 2020 were seen in Principality of Asturias, Cantabria, Extremadura, and Region of Murcia (figure 1).

Regarding cardiac computed tomography studies, 111 of the 122 centers reported the availability of this technique, a cardiologist actively participated in 37 of these 111 centers (33.3%), and the total number of studies (14 568 in 2021) recovered vs 2020 (13 137) and even increased vs 2019 (14 156).

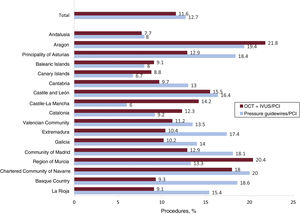

Intracoronary diagnostic techniquesThe use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques has progressively increased since 2012, with activity recovering from 2020 and even increasing vs 2019 (figure 2). Specifically, the use of pressure guidewires jumped by 19.2% vs 2020 (total, 10 347). Compared with 2020, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) grew by 22.7% (total, 5894) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) by 22.4% (total, 14 568).

IVUS/OCT was used in 11.6% of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs), while the pressure guidewire was used in 12.7% of PCIs. The distribution by autonomous community was uneven and the highest use of IVUS/OCT for PCI was recorded in Region of Murcia (20.4%) while that of pressure guidewire for PCI was found in Aragon (19.4%) (figure 3).

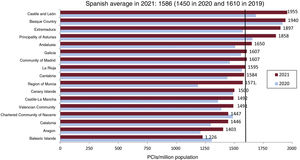

Percutaneous coronary interventionIn 2021, the number of PCIs (75 167) recovered to that of the year of the first COVID-19 lockdown (2020), with a 10.3% jump, canceling out the drop in 2020 vs 2019 (10.1%). The treatment percentages in specific subgroups were similar to those of previous years (18.4% in women, 23.2% in individuals > 74 years, and 3.8% in restenosis). Ultimately, the Spanish average was 1586 per million population (figure 4); Castile and León, the Basque Country, and Extremadura were the communities with the highest percentages. Just 22% of centers (18.2%) reported more than 1000 PCIs per year. The largest group of centers (42.1%; n=51) performed between 500 and 999 PCIs.

Similar to previous years, the most commonly used approach for PCI was the radial approach (92.9%), with a gradual increase since 2006 (29%) and an increase vs 2020 (91.1%). In line with the upward trend seen since 2013, the use of drug-eluting stents predominated (97%), with numbers similar to those of 2020 (96.7%). A total of 1.63 stents were used per PCI, similar to 2020 (1.6/PCI). The proportion of multivessel procedures was maintained vs 2020 (20.3%). The use of bioabsorbable stents and dedicated bifurcation stents was once again negligible, at 0.07% and 0.41%, respectively.

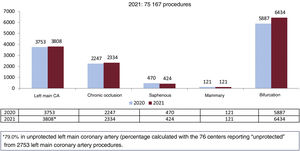

Regarding complex PCIs, such as chronic occlusions and left main coronary artery interventions, the absolute numbers increased vs 2020 but the percentage vs the total number of PCIs fell slightly (figure 5).

Complementary plaque modification techniques substantially increased vs 2020. The use of lithotripsy balloons jumped by 42% vs 2020, with a total of 1009 balloons reported. Coronary laser atherectomy also increased by 29% (95 cases in 2020 and 135 in 2021). Rotational atherectomy grew by 15.4%, reaching 1525 procedures.

Another notable aspect was the increase vs 2020 in PCI support systems such as the Impella (Abiomed, United States), of 24% (325 in total), or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, of 10.1% (168 in total). In contrast, balloon pump use fell by 9.4%, from 1020 procedures in 2020 to 924 in 2021.

Percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarctionPCI in the context of acute myocardial infarction increased again in 2021 (a 6.2% increase vs 2020) without reaching the activity levels of 2019 (21 993 in 2021 and 22 529 in 2019). Primary angioplasty showed growth of 6.2% and, in contrast, the percentages of rescue angioplasty (1.8%) and facilitated PCI (2.4%) fell vs 2020. The primary angioplasty rate increased, reaching 445 per million population (422 in 2020) (figure 6). Almost all autonomous communities recorded growth in the primary angioplasty rate vs 2020, except the Canary Islands, the Balearic Islands, the Chartered Community of Navarre, La Rioja, Galicia, and Madrid. The number of cases per center showed a largely homogeneous distribution, with 26 centers (22.4%) performing more than 300 interventions, 26 (22.4%) between 200 and 299, 22 (19%) between 100 and 199, and 42 (36.2%) between 1 and 99.

Specifically considering the centers reporting data on primary angioplasty, 90.6% used radial access. A thrombus extractor was applied in 34.6% and glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors in 14.9%. Finally, 3.4% of patients presented with cardiogenic shock requiring hemodynamic support and 6.1% developed cardiogenic shock in the first 24hours.

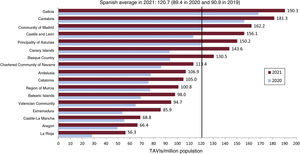

Structural catheterizationAortic valve interventionsIn 2021, the number of aortic valvuloplasties jumped by 16.9% vs 2020, reaching a total of 272 but failing to reach the 321 reported in 2019. Regardless, one of the more marked increases in the entire registry was in the number of transcatheter aortic valve implants (TAVIs), which reached 5720 procedures, 34.9% more than in 2020. The number of implants per million population also increased, reaching 120 per million (89.4 in 2020) (figure 7). Among the autonomous communities, Galicia and Cantabria continued at the head of the list, with implantation rates of 190.3 and 181.3, respectively, whereas the lowest rates were documented in La Rioja (56.3 per million) and Aragon (66.4 per million). One of the most positive aspects is probably the fact that, despite the highly marked differences among communities, all recorded an increase vs 2020. In relation to the number of procedures per center, 27 (23.5%) performed 100 or more, 18 (15.7%) reported between 50 and 99, and 70 (60.8%) reported less than 50. By age group, 66.2% of procedures were conducted in patients ≥ 80 years. A total of 197 valve-in-valve procedures were reported. The preferred access was easily percutaneous transfemoral (94.3%), followed by surgical transfemoral (2.5%), surgical transaxillary (1.9%), and transapical (1%). Other reported access routes were used in less than 1% of cases. Regarding the type of valve implanted, the following data were submitted by the centers: a) Edwards (Edwards Lifesciences, United States) in 35.8%; b) Evolut (Medtronic, United States) in 29.8%; c) Acurate Neo (Boston Scientific, United States) in 9.4%; d) Portico (Abbott Medical, United States) in 7.7%; and e) others (or not reported) in 17.2%; this group includes valves such as Lotus (Boston Scientific), MyVal (Meril, India), and Allegra (Biosensors, Singapore).

Mitral and tricuspid valve interventionsAlthough the downward trend in the number of mitral valvuloplasties was confirmed, there was still an increase in 2021 vs 2020 (187 vs 164). Nonetheless, the numbers have been gradually dropping since 2010, when 326 valvuloplasties were reported.

Mitral edge-to-edge repairs underwent a major increase, with a total of 612 interventions (438 in 2020), representing a 25.3% jump. Of these, 55.4% were performed for functional mitral regurgitation, 28.8% for degenerative, and 15.8% for mixed. MitraClip (Abbott Medical) was used in 89.7% of interventions while Pascal (Edwards Lifesciences) was used in 10.3%. Most centers (69%) performed fewer than 10 interventions, 15 centers (19%) between 10 and 19, 6 centers (7%) between 20 and 29, and 4 (5%) more than 30. The communities with the highest numbers of procedures were Andalusia, Catalonia, and Madrid. In addition, the centers reported 40 valve-in-valve procedures in the tricuspid position.

Regarding percutaneous intervention in the tricuspid valve, the data also indicated a considerable increase. In total, 98 edge-to-edge interventions were reported (37 in 2020), as well as 38 bicaval transcatheter prostheses (46 in 2020), 18 annuloplasties with Cardioband (Edwards Lifesciences), and 15 edge-to-edge repairs in the tricuspid position (15 in 2020).

Nonvalvular structural interventionsThe procedure showing the most growth vs 2020 was atrial appendage closure, from 845 to 1207 procedures (42.8% increase). This indicates a recovery from the decrease seen in 2020 and a much higher number than in 2019 (921 procedures). The distribution of the devices reported by centers was as follows: an Amulet device (Abbott Vascular, United States) was used in 627 patients, the Watchman FLX (Boston Scientific) in 457, and the LAmbre (Lifetech Scientific) in 123.

In relation to the percutaneous occlusion of paravalvular leaks, 195 patients were treated, 56 for aortic leaks and 139 for mitral leaks. This indicates a slight drop in the treatment of aortic leaks (69 in 2020) and an increase in that of mitral leaks (117 in 2020).

In addition, 132 septal ablations were reported (98 in 2020), as well as 30 coronary fistula occlusions (30 in 2020), 37 endovascular aortic repairs (25 in 2020), 25 renal denervations (18 in 2020), 15 coronary sinus reducers (16 in 2020), 21 interatrial shunts (13 in 2020), and 72 balloon pericardiotomies (74 in 2020). Finally, 124 percutaneous procedures were performed to treat acute pulmonary thromboembolisms (103 in 2020) and 91 for chronic thromboembolic disease (119 in 2020).

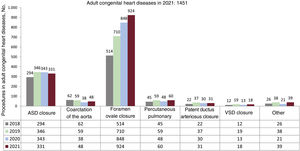

Interventions in adult congenital heart diseaseA total of 1451 procedures were performed in adult congenital heart diseases, representing an increase vs 2020 (1341). This growth was largely due to a highly marked jump in patent foramen ovale (PFO) closures (from 848 in 2020 to 924 in 2021). The remaining congenital heart diseases procedures in adults showed a slight increase vs 2020, except interatrial communication closures, which fell slightly (figure 8).

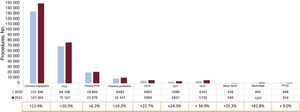

DISCUSSIONThe main findings of the ACI-SEC registry of interventional activity in 2021 were the following: a) overall activity clearly recovered compared with 2020, the year in which the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic probably had the greatest impact (figure 9); b) the numbers of procedures in ischemic heart disease increased vs 2020 and reached numbers similar to those of 2021; c) an increase was reported in the use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques (IVUS, pressure guidewire, OCT) and PCI support systems (Impella and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation); d) activity in structural heart disease maintained its strong upward trend, with highly marked increases in TAVI, mitral and tricuspid procedures, atrial appendage closure, and PFO closure; and e) there was once again marked heterogeneity among autonomous communities in the penetration of treatments with proven prognostic impact, such as primary angioplasty and TAVI.

Overview of the relative increase or decrease in each procedure in 2021 vs 2020. IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PFOC, patent foramen ovale closure; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TEER, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair.

The last registry published, which collected the activity from 2020, showed a major fall in activity, particularly in diagnostic coronary angiography, primary angioplasty, and TAVI.30 Undoubtedly, 2021 can be defined as a year of recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic, because most of the diagnostic and interventional procedures practically returned to the activity levels of 2019.29 Special mention must be made of the growth in intracoronary diagnostic techniques such as pressure guidewire, IVUS, and OCT. This increase probably reflects the recovery from the pandemic but also a growing recognition by interventional cardiologists of their usefulness.33 Indeed, the use of these techniques increased not only above 2020, but also above that of any of the previous prepandemic years, including 2019 (figure 2).

The current registry also revealed a slight increase in left main coronary artery lesions and chronic occlusions vs 2020. In addition, the data indicated the more than probable awareness of operators of the management of coronary plaque with specific techniques, with a notable increase in the use of lithotripsy balloons, special balloons (mainly cutting), and intracoronary laser or rotational atherectomy.34

Angioplasty in the context of acute myocardial infarction showed a clear decrease in treatments such as rescue and facilitated angioplasties, which became more useful during the pandemic,30 while there was a recovery in primary angioplasties, which reached a level similar to that of the prepandemic period. Notably, despite the unquestionable evidence showing that primary angioplasty is associated with reduced mortality,35 differences remain among autonomous communities, with higher rates per million population in Castile and León and Cantabria and lower rates in the Canary Islands and Balearic Islands. Particularly worrying is the reduction in this rate vs 2020 in these 2 communities. For this reason, the implementation would be recommended of specific measures in the communities with the lowest rates of primary angioplasty (figure 5).

Special mention is required of the increased activity in structural heart diseases and adult congenital heart diseases. It could be said that 2021 represents not only the year of recovery from the pandemic, but also the year with the highest structural heart disease activity of all time. In general, activity has not only increased vs 2020, but has also clearly exceeded that of 2019, the year with the greatest penetration of structural techniques to date.28–30 The increase in TAVI seems unstoppable, with a 34.9% increase vs 2020. Particularly important is the rate of procedures per million population, which increased to 120.7 (figure 7), a clearly higher rate than that of 2020 and which approaches the European average.36 The differences among communities in TAVI use are highly pronounced, with Galicia at the top of the list with 190.3 procedures per million population and La Rioja with less than 60 per million population. Although it is true that all communities underwent an increase vs 2020, the use of TAVI tripled in some communities compared with others.

Mitral and tricuspid interventions also require special mention due to their highly significant increases. The postpandemic recovery, together with the very strong scientific evidence,37 have probably contributed to the consolidation of edge-to-edge mitral repair techniques in Spain. Once again, there were major differences among autonomous communities in the penetration of this technique. Tricuspid valve interventions also markedly increased. Specifically, edge-to-edge tricuspid repair interventions demonstrated the greatest growth and practically tripled the 2020 rate (98 procedures in 2021 vs 38 in 2020). Some recent publications supporting its safety and efficacy have likely contributed to the consolidation of the technique in Spain.38

Other procedures such as left atrial appendage closure and PFO closure showed highly marked increases. Indeed, the greatest growth vs 2020 was seen in atrial appendage closure, at 42.8% (Figure 8 and figure 9). These data confirm the maturity of this technique and its penetration in Spain. Recent articles have supported its use39–41 and augur a probable paradigmatic shift in the management of patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and relative/absolute contraindications to anticoagulation. Regarding PFO closure, 2021 has been the year with the greatest penetration of the technique. Indeed, this technique was one of the few that grew in 2020. The total number of interventions in 2021 increased to 924, reaching a historic annual high since its introduction. This growth may be explained by the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, the maturity of the technique, and the general acceptance of the scientific evidence supporting PFO closure.42–44

CONCLUSIONSIn the first full year after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology Registry showed a clear overall recovery in activity vs 2020. Specifically, ischemic heart disease activity largely returned to the values recorded in 2019, and structural heart disease interventional activity progressively increased, exceeding not only that of 2020, but also that of 2019.

FUNDINGThis article has not received funding.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll authors have contributed to the drafting and critical revision of the article.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTX. Freixa is proctor for Abbott Medical and Lifetech Science. A. Jurado-Román has received honoraria for talks from Boston Scientific. B. Cid declares no conflicts of interest. I. Cruz-González is proctor for Abbott Medical, Lifetech Science, and Boston Scientific.

| Collaborator | Center |

|---|---|

| Armando Pérez de Prado | Hospital Universitario de León |

| Jose Luís Díez-Gil | Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe |

| Pablo Avanzas | Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias |

| Gerard Roura | Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge |

| Juan Horacio Alonso-Briales | Virgen de la Victoria de Málaga |

| Javier Botas-Rodríguez | Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón |

| Miguel Jerez-Valero | Hospital de Manises |

| Miguel Artaiz-Urdaci | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra (CUN) |

| Íñigo Lozano | Hospital de Cabueñes; Centro Médico Oviedo |

| José Antonio Baz | Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro |

| Juan Antonio Franco Peláez | Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz |

| Alfredo Gómez | Clínica Juaneda Palma; Hospital Universitario Son Espases |

| Ramon Calviño-Santos | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña (CHUAC) |

| Asier Subinas Elorriaga | Galdakao Usansolo |

| Juan Carlos Fernández | Hospital Universitario de Jaén |

| María José Pérez-Vizcayno | Hospital Clínico San Carlos |

| Juan Francisco Oteo-Domínguez | Hospital Puerta de Hierro |

| Jesús Jiménez | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Albacete |

| Koldobika García-San Román | Hospital Universitario de Cruces |

| Ramón López-Palop | Hospital Quirón Torrevieja |

| José Antonio Diarte-De Miguel | Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet |

| Roberto Sáez-Moreno | Hospital Universitario Basurto |

| Ricardo Fajardo-Molina | Hospital Torrecárdenas; Hosptal Vithas Virgen del Mar |

| Ignacio Sánchez-Pérez | Hospital General Universitari de Ciudad Real |

| Javier Zueco | Hospital de Valdecilla |

| Antonio Ramírez-Moreno | Hospital de Estepona |

| Juan Antonio Bullones-Ramírez | Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga |

| Alfonso Miguel Torres Bosco | Hospital Universitario Araba-Txagorritxu |

| Jaime Elízaga | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón |

| Juan Manuel Casanova | Hospital Arnau de Vilanova |

| Dabit Arzamendi | Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau |

| Antonio Enrique Gómez-Menchero | Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez de Huelva |

| Ignacio Cruz-González | Hospital Universitario de Salamanca |

| Bruno García-Del Blanco | Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron; Hospital Universitari Dexeus |

| Joaquín Sánchez-Gila | Hospital Virgen de las Nieves |

| Ignacio J. Amat-Santos | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid; Hospital Recoletas Campogrande |

| Juan Miguel Ruiz-Nodar | Hospital Clínica Benidorm; Hospital General Universitario de Alicante |

| Manuel Vizcaino-Arellano | Hospital Virgen Macarena |

| Antonio Merchán-Herrera | Hospital Universitario de Badajoz |

| Vicente Mainar | Hospital IMED Levante |

| Carlos Macaya | Hospital Vithas La Milagrosa; Hospital Vithas Nuestra Señora de América; Clínica Nuestra Señora del Rosario |

| Jose Ramón Ruiz-Arroyo | Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa |

| Mariano Larman-Tellechea | Policlínica Gipuzkoa-Hospital Donostia |

| José Moreu-Burgos | Hospital Universitario de Toledo |

| Julio Carballo-Garrido | Centro Médico Teknon |

| Francisco Javier Lacunza-Ruiz | Hospital Quirónsalud Murcia |

| Eduard Bosch | Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí |

| Javier Fernández-Portales | Hospital de Cáceres |

| Eduardo Pinar-Bermúdez | Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca; Hospital HLA La Vega |

| Francisco Manuel Jiménez-Cabrera | Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria |

| Raúl Moreno | Hospital Universitario La Paz |

| Beatriz Vaquerizo | Hospital del Mar |

| Leire Unzué | Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe |

| Eulogio García | Hospital Moncloa |

| Enrique Novo-García | Hospital General Universitario Guadalajara |

| Ramiro Trillo-Nouche | Hospital Clínico de Santiago de Compostela |

| Pedro Martín-Lorenzo | Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín |

| Ángel Sánchez-Recalde | Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal; Hospital Universitario la Zarzuela; Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Moraleja |

| Juan Carlos Rama-Merchán | Hospital de Mérida |

| Luís Antonio Íñigo-García | Hospital Costa del Sol |

| Mohsen Mohandes | Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII |

| Agustín Guisado-Rasco | Hospital Virgen del Rocío |

| Alberto Berenguer-Jofresa | Hospital General Universitario de Valencia |

| Juan Ruiz-García | Hospital Universitario de Torrejón |

| Raymundo Ocaranza-Sánchez | Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti |

| Juan Francisco Muñoz Camacho | Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa |

| Manel Sabaté | Hospital Clínic de Barcelona |

| Salvador Álvarez-Antón | Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla |

| Armando Bethencourt | Hospital Quirónsalud Palmaplanas |

| Agustín Fernández-Cisnal | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia |

| Francisco Pomar Domingo | Hospital de La Ribera |

| Juan Caballero | Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio |

| Alejandro Gutiérrez-Barrios | Hospital Puerta del Mar |

| María Pilar Portero-Pérez | Hospital San Pedro de Logroño |

| José Domingo Cascón-Pérez | Hospital Santa Lucía |

| Leire Andraka | Clínica IMQ Zorrozaurre |

| Soledad Ojeda-Pineda | Hospital Reina Sofía; Hospital Quirónsalud Córdoba |

| Araceli Frutos-García | Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante |

| Valeriano Ruiz-Quevedo | Hospital Universitario de Navarra |

| Mariano Usón | Hospital Juaneda Miramar |

| Fernando Sarnago-Cebada | Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre |

| Fernando Rivero-Crespo | Hospital Universitario de la Princesa |

| Jorge Palazuelos Molinero | Hospital de La Luz; Hospital Quirónsalud Sur Alcorcón |

| Francisco José Sánchez-Burguillos | Hospital Universitario de Valme |

| Rafael García de la Borbolla-Fernández | Viamed Santa Angela de la Cruz |

| Eduardo Alegría-Barrero | Hospital Ruber Internacional |

| María Eugenia Vázquez Alvarez | Hospital San Rafael de Madrid |

| Javier Suárez de Lezo | Clínica de la Cruz Roja |

| Sara María Ballesteros-Pradas | Hospital Quirón Sagrado Corazón |

| Raquel Pimienta-González | Complejo Hospitalario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria |

| Rosa Sánchez-Aquino | Hospital Rey Juan Carlos |

| Santiago Jesús Camacho-Freire | Hospital San Agustín |

| Francisco José Morales-Ponce | Hospital Universitario Puerto Real |

| Paula Tejedor | Hospital General Universitario de Elche |

| Belén Rubio-Alonso | Hospital Quirónsalud Madrid; Clínica Ruber Juan Bravo |

| Xavier Carrillo-Suárez | Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol |

| Javier Robles Alonso | Hospital Universitario de Burgos |

| Víctor Hugo Agudelo-Montáñez | Hospital Universitario Josep Trueta |

| Carlos Arellano-Serrano | Clínica Universidad Navarra - Madrid |

| Francisco Bosa-Ojeda | Hospital Universitario de Canarias |

| David Tejada-Ponce | Hospital General Universitario de Castellón |

| Xavier Freixa | Hospital General de Catalunya |

| Daniel Núñez-Pernas | Hospital de Vinalopó |

| Miguel Leiva Gordillo | Hospital de Denia |

| Pascual Baello Monge | Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset |

| Eva González-Caballero | Hospital Universitario de Jerez de la Frontera |

| Manuel J. Vargas-Torres | Hospital Rambla Sur |