The Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology presents its annual report on the data from the registry of the activity in Spain in 2014.

MethodsData were voluntarily provided by participating centers. The information was introduced online and was analyzed by the Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology.

ResultsData were reported by 106 hospitals. A total of 140 461 diagnostic procedures (125 484 coronary angiograms) were performed, representing a rate of 3014 diagnostic studies per million population. This year, the number of percutaneous coronary interventions increased to 67 611, giving a rate of 1447 interventions per million population. A total of 94 458 stents were implanted, including 64 057 drug-eluting stents and 2424 biodegradable intracoronary devices. Of the total number of percutaneous coronary interventions, 17 825 were in acute myocardial infarction, representing 26.4% of all coronary interventions. A radial approach was used in 74% of diagnostic procedures and in 70.4% of interventional procedures. The use of renal denervation decreased, whereas over 125 mitral leak closures were performed. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedures exceeded 1300 implantations per year, a 27% increase from 2013.

ConclusionsThe registry for 2014 shows a slight increase in coronary disease activity despite no increase in the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Drug-eluting intracoronary devices now comprise over 70% of all intracoronary devices. A continual increase is only seen in certain structural interventional techniques, such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation and perivalvular leak closure.

Keywords

This year, continuing the annual tradition that began in 1990 and which is considered one of its most important tasks, the Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology has collected data on the activity of as many cardiac catheterization laboratories as possible in order to perform the annual registry of their activity. The data collection has gradually been perfected in recent years1–23 with the introduction of online data entry. The data are cleaned by both the members of the steering committee and those of the working group because the preliminary data are presented at the group's annual meeting, held this year on June 11th and 12th on the island of Madeira.

The registry of the annual activity primarily enables analysis of the year-on-year changes in activity, an important factor when determining the extent of the implementation of percutaneous techniques in Spain. Per hospital and per community analyses establish a framework for comparing the differences in the activity in both absolute and relative terms by adjusting the data for the census population of each community. Despite the limitations of a voluntary registry of activity, the information obtained enables the situation in Spain to be determined and compared with that of other countries and allows us to assess the development of interventional cardiology in the different Spanish autonomous communities. The free availability of these data helps resource distribution to be determined and allows us to evaluate the various trends in the use of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

Although use of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has plateaued in recent years, changes were still evident in some of the variables. Despite the development of various infarction care programs by the autonomous communities and the Infarction Code Program, shown to increase the number of patients seen and reduce waiting times,24 the use of PCI slightly decreased in the management of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). However, the use of coronary interventional procedures in general continues to grow and the numbers of stent implantations are stable, with a clear tendency for the increasingly predominant use of drug-eluting devices. These trends may have been influenced by the good results obtained for second-generation drug-eluting stents and less than 12-month antiplatelet therapy in Spain,25,26 as well as by the development of the European Stent for Life initiative, which aims to improve infarction care and has set Spain as one of its “target” countries.27 The 2 structural heart disease techniques whose use continues to increase despite the economic situation are perivalvular leak closure and, particularly, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

This article presents the 24th report on Spanish interventional activity and covers the activity of all public centers and a considerable number of private centers.

METHODSData were collected on the diagnostic and interventional cardiac activity of most Spanish centers. Data collection is voluntary and is not audited. If data were conflicting or deviated from the trend observed in a center in recent years, the institutes in question were contacted for the reassessment of the data. Data were collected via a standard electronic questionnaire that could be accessed, completed, and consulted through the website of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.21 The information obtained was analyzed by the working group's steering committee, in collaboration with the Persei Consulting group. The results are published here but a preliminary draft was presented as a slideshow at the working group's annual meeting.

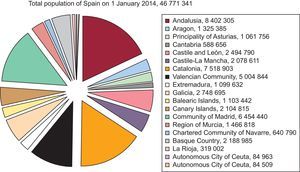

The population-based calculations, those of both Spain and each autonomous community, were based on the population estimates of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics up until January 1st 2014 and as published on its website.28 The Spanish population was estimated to have increased to 46 771 341 inhabitants (Figure 1). As in the most recent years, the number of procedures per million population for the country as a whole was calculated using the total population. This year, as before, rather than the number of diagnostic procedures per million population, the true number of coronary angiograms per million population was evaluated. The latter figure can be compared with the European recommendations and averages.

Population of Spain on 1 January 2014. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.28

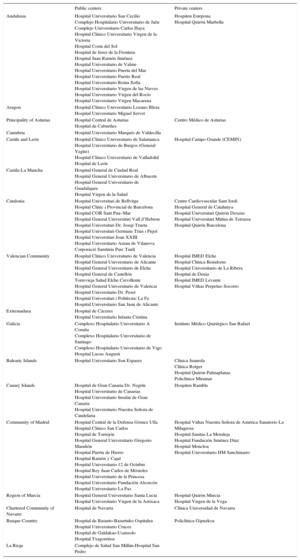

A total of 106 hospitals performing interventional procedures in adults participated in this registry; most centers (n=75) were public (Appendix). This participation represents a substantial proportion of the Spanish activity, with most of the volume attributable to publically financed centers. There were 208 catheterization laboratories: 136 (65%) were exclusively for cardiac catheterization, 13 (6%) were hybrids, and 59 (28%) had shared activity.

The 106 centers reported a total of 693 physicians performing interventional activity in 2014 (368 of them accredited). Additionally, there were 557 registered nurses and 88 radiology technicians.

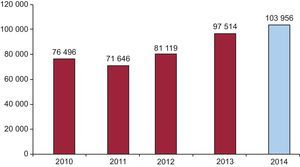

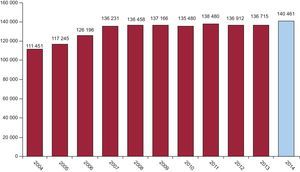

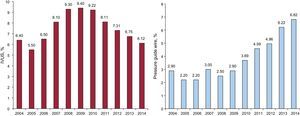

Diagnostic ProceduresDuring 2014, 140 461 diagnostic studies were performed, representing an increase of 2.7% over the previous year. Of these procedures, 125 484 were coronary angiograms. Notably, 103 957 diagnostic procedures were performed using a radial approach. This number represents 71.3% of all procedures, with a constant increment in recent years (Figure 2); particularly relevant is the 20% increase reported from 2012 to 2013. The national average of diagnostic studies per million population was 3014, a slight increase from 2013 (2944 procedures). This datum was previously reported as coronary angiograms per million population. When strictly referring to coronary angiograms, this figure was actually 2693 procedures per million population (2592 in 2013), markedly lower than the European estimations of 2006.25 The changes in diagnostic procedures performed since 2004 are shown in Figure 3.

Regarding the diagnostic activity per center, 62 institutions performed more than 1000 coronary angiograms (4 more than in 2013) and 16 performed more than 2000 (17 in 2013). The overall average was similar to that of recent registries18–23 at 1338 diagnostic procedures per center.

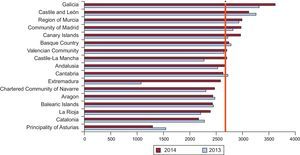

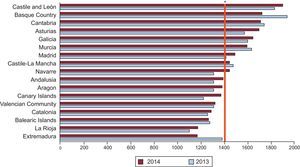

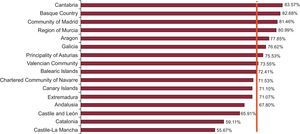

The distribution of diagnostic coronary angiograms per million population according to autonomous community is shown in Figure 4. The average per million population was 2693, slightly higher than that recorded in 2013 (2592 coronary angiograms per million population).

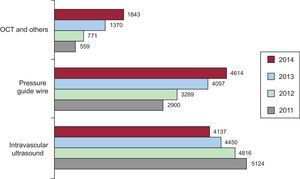

Once the most widely used intracoronary diagnostic technique, recent trends show a reduced use of intracoronary ultrasound in favor of a steady increase in the use of the pressure guide wide; again, the greatest percentage increase corresponded to optical coherence tomography, with 34.5% growth in 2014. The changes during the last 3 years in the various intracoronary diagnostic techniques are shown in Figure 5.

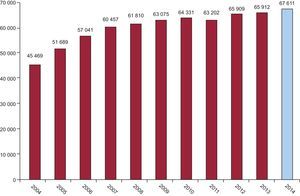

Percutaneous Coronary InterventionsThe number of PCIs increased slightly from the previous year, reaching 67 611 procedures (65 912 in 2013). The changes in PCI use over time are shown in Figure 6. The number of PCIs per million population was 1447 (vs 1419 in 2013 and 1434 in 2012). All centers with diagnostic activity also performed PCI.

The PCI to coronary angiography ratio was 0.54 (vs 0.55 in 2013 and 2012). In 2014, procedures for multivessel disease comprised 25% of all procedures (30% in 2013 and 24.8% in 2012). Fewer procedures were performed ad hoc during diagnosis (71% in 2014 vs 74% in 2013).

Use of radial access in PCI increased again, by 6% this year, and now shows a prevalence of 70.4%, only 4% lower than in diagnostic procedures.

With 2028 interventions (2202 in 2013 and 1810 in 2012), there was no increase in the number of procedures involving the unprotected left main coronary artery. This number represents just 3% of the total, despite repeated evidence from studies with long-term clinical follow-up of good outcomes in patients randomized to PCI if the disease does not involve the rest of the coronary tree.

The registry recorded 2852 procedures (2751 in 2013) to treat lesions considered by the operator to be chronic total occlusions, representing 4.2% of all PCIs.

Adjuvant drug therapy involving glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and antithrombotic agents (besides unfractionated heparin) was used in 15.3% of procedures; the most widely used drugs were abciximab (in 8.5% of PCIs) and bivalirudin (in 4.5%), respectively.

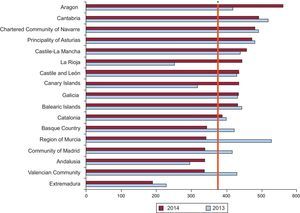

The distribution according to autonomous community of the 1447 PCIs per million Spanish population is shown in Figure 7. As usual, the distribution according to center was bimodal: while 26 centers performed fewer than 250 PCIs per year, with most private centers in this category, 45 centers performed between 500 and 1000 PCIs. There were 22 high-volume centers (> 1000), representing an increase from the 18 of the previous 2 years.

The intracoronary diagnostic techniques (intravascular ultrasound and pressure guide wire), used mainly to evaluate intermediate lesion severity or intervention outcomes, maintain the dynamic of the previous 6 years: use of intracoronary ultrasound decreased to 6.1% of interventions (use of optical coherence tomography in this setting was not recorded), whereas guide wide use increased to 6.8% (Figure 8).

This year, as before, information on immediate outcome variables in PCI were provided in 71% of cases; 98.4% were considered to have been successfully performed without complications, 1.2% reported severe complications (death, AMI, or the need for emergency cardiac surgery), and only 0.4% reported intraprocedural death.

StentsThe implantation of 94 458 stents was reported in 2014, almost 5000 fewer than in 2013. Although this variable is highly dependent on the total number of centers reporting data (close to 90%), we believe that increased use of longer stents avoids the need for stent overlap and reduces the number of stents per patient. Indeed, for the first time in 6 years, the stent to patient ratio was clearly reduced to less than 1.5, with a figure of 1.4 (1.5 in 2013, 1.6 in 2010, and 1.8 in 2008). In 2014, the market penetration of drug-eluting stents clearly increased, reaching 67.8% (61.5% in 2013 and 61.8% in 2012), or 64 057 units. However, this is a pure ratio between the total number of drug-eluting stents and the total number of stents and fully biodegradable devices (2424 reported devices vs 1384 in 2013) represented 2.5%. Thus, the total number of drug-eluting devices reached 70% for the first time (see below for the percentage device penetration per autonomous community). Use of self-expanding intracoronary devices and those specifically designed for the treatment of bifurcations increased to 114 (79 in 2013) and 332 (267 in 2013) procedures, respectively. The prevalence of direct stent implantation was lower than in previous years, about 25%, but this figure is similar to that reported in recent studies or data sets dealing with “real world” lesions.29

Wide variability continues to be seen in the implementation of drug-eluting stents among autonomous communities. Because the lack of data on drug-eluting stents could greatly affect the ratio in some of the communities with fewer centers, we have tried to clean the datum by eliminating from the calculation the centers not providing information on this variable. This aspect explains why the total ratio is 71.4% and why some communities have been omitted, such as La Rioja (Figure 9).

Other Devices and Procedures Used in Percutaneous Coronary InterventionsThe use of rotational atherectomy has plateaued compared with recent years with 1021 cases in 2014 (1254 in 2013), distributed among 71 centers, as in the last 3 years. The use of the cutting balloon grew once again to 2355 cases (2103 in 2013 and 1982 in 2012), with no distinction among the scoring balloon models. Thrombectomy catheter use has decreased for the first time. It was used in 8981 cases (9370 in 2013 and 9041 in 2012), a 4.1% decrease compared with 2013. This decrease is undoubtedly related to the recently published results of the TOTAL study,30 as well as those of the TASTE study31 of the previous year, that rule out clinical benefit from the systematic use of thrombectomy in primary angioplasty. Nonetheless, these devices were still used in 61.2% of primary PCIs in 2014.

Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in Acute Myocardial InfarctionThe 17 825 PCIs reported in the management of AMI as a general group represents a surprising decrease of 2.7% from the 18 337 in 2013 (17 125 in 2012). Nonetheless, they continue to account for more than a quarter of all PCIs (26.4% of the total number of PCIs). Of these 17 825 PCIs, a radial approach was used in 12 373 (69.4% vs 61.4% in 2013, 56% in 2012, and 49% in 2011).

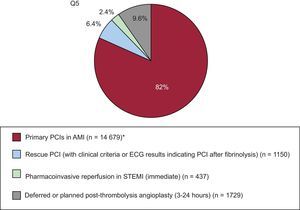

Notably, there was a 5.6% increase in the use of primary angioplasty (14 679 cases in 2014 vs 13 899 in 2013) while the other types of PCIs performed in the acute phase of AMI showed a general decrease. In fact, angioplasty was immediately performed in 437 cases in 2014 vs 671 cases in 2013, deferred to between 3 and 24hours after administration of fibrinolytic therapy in 1729 cases (1902 in 2013), and consisted of rescue angioplasty in 1150 cases (1359 in 2013). Primary PCIs represented 21.7% of all angioplasty procedures and 76.6% of all PCIs performed in AMI (Figure 10).

There was wide variability in the national distribution of PCIs in AMI by autonomous community; however, continuous care programs in AMI have recently been organized in some communities and some communities with few centers and data collection problems are highly sensitive to changes from previous years, hindering reliable interpretation of the data (Figure 11).

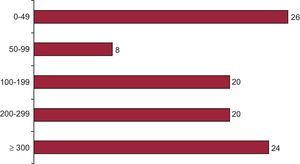

Regarding the number of procedures per center, 44 centers performed more than 200 PCIs in AMI per year (the same as in 2013), whereas 26 performed fewer than 50 (3 more than in 2013) (Figure 12).

Noncoronary Interventions in AdultsThere have been spectacular changes in the percutaneous treatment of valve disease that have not been accurately reflected in the number of valvuloplasty procedures—the number of both mitral (256 vs 240 cases in 2013) and aortic (229 vs 201 in 2013) valvuloplasties have only slightly increased—but have been reflected in the use of more innovative techniques. In the current registry, only information on transcatheter aortic valve implantation is requested. Use of this procedure increased to 1324 implantations in 2014 (a 27% increase vs the 1041 in 2013). Although the Spanish longitudinal data on transcatheter aortic valve implantation in the last 5 years is not exponential, with 426 in 2009, 655 in 2010, 770 in 2011, and 845 in 2012, the increased use of the technique in Europe is clear. No registry data were available on the number of cases of MitraClip® mitral valve repair.

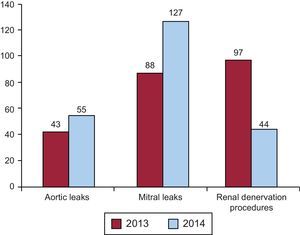

Data on the treatment of adult congenital heart disease continue to be similar to those of previous years, with 292 closures of atrial septal defects and 201 patent foramen ovale closures. Surprisingly, there was a slight increase compared with 2013 in other closure procedures, such as those involving the left atrial appendage, with only 51 procedures (8 more than in 2013), despite the positive experiences in Spanish centers.32 There was a notable increase in paravalvular leak closure, both mitral—127 (88 in 2013, 67 in 2012)—and aortic—55 (43 in 2013 and 31 in 2012)—in agreement with the broad experience of Spanish groups.33,34 The 44 renal denervation procedures in 2014 were a sharp fall from the 97 in 2013 and 61 in 2012; this decrease is probably related to the data of the Symplicity HTN–2 study35 (Figure 13).

DISCUSSIONThe activity reported in 2014 continued to show slight changes in some of the dynamics of interventional cardiology: after a number of years without changes, the role of PCIs is now more physiological or functional than visual, now that the pressure guide wire is the most commonly used supporting technique during PCI. Angioplasty in the management of AMI is focused on primary angioplasty, the only modality showing continued increases, as well as paravalvular leak closure and renal denervation. Data on coronary devices revealed a clear general increase in the use of drug-eluting stents, including biodegradable devices; bare metal stents are now used in barely 30% of cases. In structural heart disease, there was a clear increase in transcatheter valve implantations and growth in paravalvular leak closure.

In Spain, the reported numbers of many techniques are still below the European average, particularly PCIs per million population, transcatheter aortic valve implantation, and atrial appendage closure, with rates markedly lower than those of other European countries.36

Diagnostic activity slightly increased but the actual rate of coronary angiography per million population was much lower than the European data for 2005: 2693 coronary angiograms per million population vs 4030.37 Interventional activity increased, although slightly. This increase was not due to the growth in primary angioplasty, which was just 5.6% compared with 2013. No particular increase was seen in the number of “complex” percutaneous coronary revascularization cases, despite the promising results of relevant studies.38–41 The number of stent implantations decreased, as well as the stent per patient ratio and the number of bare metal stents. The publication of the FREEDOM study38 in diabetic patients and the long-term results of the SYNTAX trial39,40 have surely discouraged aggressive and complete percutaneous treatment of patients with multivessel and complex anatomy. However, as before, the registry shows more widespread use of the pressure guide wide, undoubtedly for decision making, as recommended by the FAME study.42 This approach could reduce both the number of PCIs performed and the number of lesions treated and stents used, even in patients with multivessel disease. The implementation of long stents (> 30 mm) in catheterization laboratories may also have helped to maintain a low stent per patient ratio.

Despite the slight increase in coronary interventional activity in Spain, the intervention rates per million population are still much lower than those of the rest of Europe, especially given that the Spanish PCI rate of 1447 per million population is lower than the European PCI of 1601 per million population of a decade ago.37

Undoubtedly, one of the indicators of the quality of care in Spanish hospitals that is irrespective of care networks or available budgets is the rate of radial vascular access, which is growing year-on-year. In 2014, the rate reached 70%, particularly in settings where the benefit is clear, such as angioplasty in AMI.43 Transcatheter aortic valve implantation is also growing, although its annual implantation rates are much lower than those of Europe.

CONCLUSIONSAlthough there was a general leveling off in activity, the registry data for 2014 show some interesting changes and differences from previous years. The progressive increase in primary angioplasty continues, due to both the incorporation of new autonomous communities to the primary PCI program and the marked increase in new centers.

Although there are differences among autonomous communities in coronary interventional activity in general and infarction in particular, the use of drug-eluting stents has grown throughout Spain, as well as that of completely biodegradable devices. However, in absolute terms, fewer stents are being used and the stent per patient ratio is lower. In addition, the most widely used adjunctive diagnostic technique is currently the pressure guide wire.

Regarding noncoronary interventional procedures, there is still a slow growth in transcatheter aortic valve implantation and treatment of paravalvular leaks and a clear decrease in renal denervation.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

The Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology wish to thank the directors and personnel of cardiac catheterization laboratories throughout Spain, as well as those responsible for the data collection, for their work.

| Public centers | Private centers | |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | Hospital Universitario San Cecilio Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Jaén Complejo Universitario Carlos Haya Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria Hospital Costa del Sol Hospital de Jerez de la Frontera Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez Hospital Universitario de Valme Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar Hospital Universitario Puerto Real Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | Hospiten Estepona Hospital Quirón Marbella |

| Aragon | Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | |

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital Central de Asturias Hospital de Cabueñes | Centro Médico de Asturias |

| Cantabria | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | |

| Castile and León | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca Hospital Universitario de Burgos (General Yagüe) Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid Hospital de León | Hospital Campo Grande (CEMIN) |

| Castile-La Mancha | Hospital General de Ciudad Real Hospital General Universitario de Albacete Hospital General Universitario de Guadalajara Hospital Virgen de la Salud | |

| Catalonia | Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona Hospital COR Sant Pau–Mar Hospital General Universitari Vall d’Hebron Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Trueta Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí | Centre Cardiovascular Sant Jordi Hospital General de Catalunya Hospital Universitari Quirón Dexeus Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa Hospital Quirón Barcelona |

| Valencian Community | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia Hospital General Universitario de Alicante Hospital General Universitario de Elche Hospital General de Castellón Torrevieja Salud Elche Crevillente Hospital General Universitario de Valencia Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante | Hospital IMED Elche Hospital Clínica Benidorm Hospital Universitario de La Ribera Hospital de Denia Hospital IMED Levante Hospital Vithas Perpetuo Socorro |

| Extremadura | Hospital de Cáceres Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina | |

| Galicia | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo Hospital Lucus Augusti | Instituto Médico Quirúrgico San Rafael |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Espases | Clínica Juaneda Clínica Rotger Hospital Quirón Palmaplanas Policlínica Miramar |

| Canary Islands | Hospital de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín Hospital Universitario de Canarias Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria | Hospiten Rambla |

| Community of Madrid | Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla Hospital Clínico San Carlos Hospital de Torrejón Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón Hospital Puerta de Hierro Hospital Ramón y Cajal Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre Hospital Rey Juan Carlos de Móstoles Hospital Universitario de la Princesa Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón Hospital Universitario La Paz | Hospital Vithas Nuestra Señora de América Sanatorio La Milagrosa Hospital Sanitas La Moraleja Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz Hospital Moncloa Hospital Universitario HM Sanchinarro |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca | Hospital Quirón Murcia Hospital Virgen de la Vega |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Hospital de Navarra | Clínica Universidad de Navarra |

| Basque Country | Hospital de Basurto-Basurtuko Ospitalea Hospital Universitario Cruces Hospital de Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital Txagorritxu | Policlínica Gipuzkoa |

| La Rioja | Complejo de Salud San Millán-Hospital San Pedro |