The Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) presents its annual activity report for 2020, the year of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

MethodsAll Spanish centers with catheterization laboratories were invited to participate. Data were collected online and were analyzed by an external company, together with the members of the ACI-SEC.

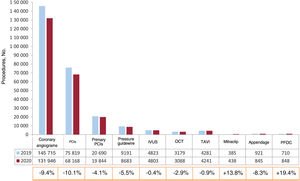

ResultsA total of 123 centers participated (4 more than 2019), of which 83 were public and 40 were private. Diagnostic coronary angiograms decreased by 9.4%, percutaneous coronary interventions by 10.1%, primary percutaneous coronary interventions by 4.1%, transcatheter aortic valve replacements by 0.9%, and left atrial appendage closure by 8.3%. The only procedures that increased with respect to previous years were edge-to-edge mitral valve repair (13.8%) and patent foramen ovale closure (19.4%). The use of pressure wire (5.5%), intravascular imaging devices and plaque preparation devices decreased (with the exception of lithotripsy, which increased by 62%).

ConclusionsIn the year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the registry showed a marked drop in activity in all procedures except for percutaneous mitral valve repair and patent foramen ovale closure. This decrease was less marked than previously described, suggesting a rebound in interventional activity after the first wave.

Keywords

Since 1990, the Steering Committee of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC) has collected activity data from cardiac catheterization and interventional cardiology laboratories in Spain.1–5 The data typically obtained from the national registry are very important because they shed light on the changes over time in interventional activity volume in Spain, the implementation and growth of new techniques and health care networks, and the variability among different regions. The annual registry proves the transparency of all of the registry centers and their commitment to continuous improvement.

In addition, the 30th registry report (1990-2020) is particularly important because it is a record of the first year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Various articles have shown that interventional activity significantly fell in the first months of the pandemic (March to May 2020) due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related saturation of the health care system, the drop in health care seeking due to fear of infection, or the effect of competing risk.6–9 Thus, the present registry is vital for estimating the overall and regional impact of the pandemic on interventional activity in Spain in 2020.

Data were submitted voluntarily, online, and without audit. The database, which has been updated, is managed by an independent external company. Subsequently, the ACI-SEC committee cleaned the data, which were presented to the public in an online seminar on June 29, 2021, and in-person at the ACI-SEC congress in September 2021 in Málaga.

The objective of the present article was to present the 30th report on interventional activity in Spain, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODSDesignThe registry is retrospective and voluntary and the data are submitted online and without audit. The registry comprises 295 variables; 50 must be completed. Data collection was performed via an online database that was accessed through a link sent by e-mail to the responsible researcher in each center or through the ACI-SEC website.10 The study period ran from January 1 to December 31, 2020. Data collection took place between April and May, 2021.

An external company (Tride, Madrid) and members of the ACI-SEC committee analyzed the data together. The data were cleaned by the ACI-SEC committee, and discordant data or data deviating from the trend in a center were verified with researchers in the center in question. None of the data from this registry have been published, although a summary was presented in the above-mentioned online seminar.

Absolute (n) and relative (%) data are reported. Comparisons were made with previous years and also among different autonomous communities.

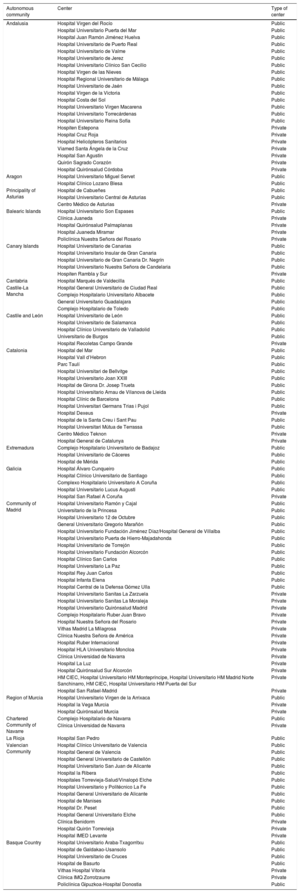

Study populationVia e-mail and/or telephone call, 126 hospitals were invited to participate; 84 were public and 42 were private (appendix 2). The study population was taken from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics for January 1, 2020.11 The Spanish population was estimated at that time to be 47 450 795 inhabitants. The number of procedures per million population for the country as a whole was calculated using the total population.

RESULTSInfrastructure and resourcesIn 2020, 123 of the 126 invited centers participated (97.6%). Of the 84 publicly-funded centers invited, 83 provided data (98.8%), while 40 of the 42 private centers provided data (95.2%). This represented an increase vs previous years (107 in 2017, 109 in 2018, 119 in 2019, and 123 in 2020). Compared with 2019, the same number of publicly-funded centers participated (n=83) but there were 4 more private centers (36 in 2019 and 40 in 2020). In addition, 281 catheterization laboratories were recorded (vs 263 in 2019); of these, 160 (56.9%) were exclusively for cardiac catheterization, 77 (27.4%) were shared, 31 (11%) were hybrid, and 13 (4.7%) were supervised.

Regarding human resources, the centers reported that 496 interventional cardiologists, most (468) accredited by the ACI-SEC; 112 (23.9%) were women, which was a similar percentage to 2019 (23.7%). The number of fellows fell once again (67 vs 79 in 2019 and 90 in 2018). There was a slight uptick in the number of registered nurses (739) and radiology technicians (94).

Diagnostic activityIn the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns, interventional diagnostic activity fell by 10.7% in Spain (147 000 vs 165 124 in 2019), which broke the upward trend of previous years and returned the levels to those of 2014. Of these procedures, most were coronary angiograms (131 946, a 9.4% reduction vs 2019), followed by endomyocardial biopsies and studies of patients with valvular heart disease.

As a consequence of the reduced activity, just 15 centers (12.3% of participating centers) performed more than 2000 coronary angiograms, vs 20 centers (16.8%) in 2019. As in previous years, the preferred access route was radial (90.5% of studies). The national average of coronary angiograms fell to 2806/million population; the steepest falls were recorded in the Region of Murcia, Cantabria, and Castile-La Mancha, while the lowest reductions per million population were in the Balearic Islands and the Chartered Community of Navarre.

Regarding cardiac computed tomography studies, 111 of the 122 centers reported the availability of this technique; the number of examinations fell from 14 156 in 2019 to 13 137 in 2020.

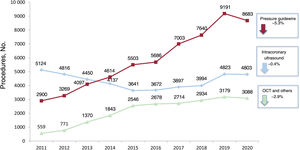

Intracoronary diagnostic techniquesPressure guidewire use consistently increased from 2011 to 2019, eventually tripling the original level. However, it fell in 2020 by 5.3% to 8683 procedures (figure 1). Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was relatively stable and optical coherence tomography dropped by 2.9%.

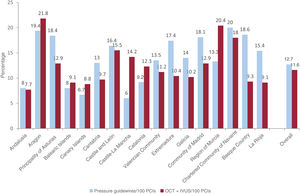

The highest penetrance of pressure guidewire or intravascular imaging was asymmetrical among autonomous communities (figure 2). Pressure guidewire use was highest in Navarre, the Basque Country, and Aragon (with 19 guidewires/100 percutaneous coronary interventions [PCIs]) and lowest in Castile-La Mancha and the Canary Islands (6/100 PCIs). In contrast, the highest penetrance of intravascular imaging was in Aragon and Murcia (21 and 20/100 PCIs, respectively); the lowest was in Andalusia and the Canary Islands.

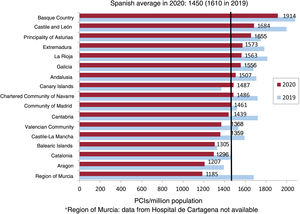

Coronary interventionsDuring the first year of the pandemic, the number of PCIs fell by 10.1%. Its levels are now around those of 2015. This reduction paralleled that in diagnostic activity because the PCI/coronary angiogram ratio was unchanged from previous years (0.52). The decrease also did not disproportionately affect any subgroup of patients because the percentages of women (19.1%) and patients older than 74 years (21%) were stable. The average rate in Spain was 1450 PCIs/million population (figure 3); the highest rates were seen in the Basque Country and Castile and León, as in previous years. Only 2 centers reported more than 1500 PCIs, while just 17 documented more than 1000 (13.9% of centers vs 22.7% in 2019).

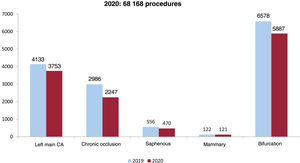

Radial access became consolidated as the most commonly used approach for PCI and has maintained an upward trend from 2006 (29%) to 2020 (91.1%). Drug-eluting stent use became the norm in 2020; of 92 771 implanted stents, 89 706 were drug-eluting stents and all autonomous communities except Murcia (88%) exceeded 94%. The use of bioabsorbable devices or dedicated bifurcation stents was limited (<0.5%). Regarding the PCI type, most interventions were single-vessel PCIs and only 20% were multivessel. The stent/angioplasty ratio was similar to that of previous years (1.6 stents/PCI). Complex and high-risk interventional procedures also fell in the first year of the pandemic, with a highly pronounced reduction in the number of chronic occlusions (−25%) and of left main coronary artery interventions (a drop of 380 procedures [9.2%]) (figure 4). All plaque and calcium modification techniques fell, except lithotripsy, which increased by 62% to reach 586 balloons/y. The rotational atherectomy/lithotripsy ratio fell from 4.5 in 2019 to 2.2 in 2020. Circulatory assist device use was similar to that of previous years—247 Impella (Abiomed, United States) and 1020 balloon pumps—but extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) use increased by 34% (from 113 in 2019 to 151 in 2020). This increase was probably related to COVID-19.

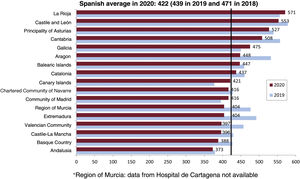

Coronary interventions in acute myocardial infarctionIn 2020, coronary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction dropped by 1490 procedures to 21 039 (−5.5%). Of these, 94.3% were primary angioplasties; the remainder were rescue angioplasties or angioplasties after successful fibrinolysis. Primary angioplasty showed the steepest fall, while rescue angioplasty increased by 17%. The percentage of women fell from 27.8% in 2019 to 25% in 2020. The primary angioplasty rate fell in Spain to 422/million population (figure 5). This reduction occurred in most autonomous communities, except La Rioja, Galicia, the Canary Islands, and Madrid. Primary PCIs represented 29.5% of all angioplasties, a slight increase vs previous years. Regarding the number of primary angioplasties/center, the number of centers performing more than 300 primary angioplasties decreased from 26 to 2019 to 20 to 2020. At the other extreme, the number performing fewer than 50 increased from 34 to 40.

Concerning the technical aspects of primary angioplasty, the radial approach was the norm (91.1%), as in conventional angioplasty. Despite evidence against them, thrombus aspiration devices were used in 34% of cases. Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors were administered in 16.4% of cases.

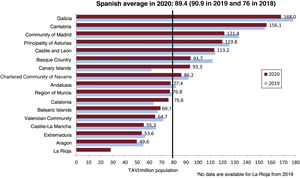

Aortic valve interventionsIn 2020, 226 aortic valvuloplasties were performed, 30% fewer than in the previous year and a return to 2014 levels. The number of transcatheter aortic valve implantations (TAVIs), which had been consistently growing at about 20% to 37% per year since 2014, fell by 0.9% (4241 implants). Of these, 185 involved device implantation within another failed bioprosthesis (valve-in-valve). TAVI number per million population in Spain was 89.4 (figure 6) vs 90.9 in 2019. Cantabria, the Canary Islands, Catalonia, and the Balearic Islands showed increases from 2019, while the TAVI number per million population fell in the remaining autonomous communities. Nonetheless, the communities with the most TAVIs per million population were Galicia, Cantabria, and Madrid. Just 16 centers (14%) performed more than 100 implants, while most (75 centers, 65.8%) performed fewer than 50.

Regarding the technical aspects, transfemoral access was the approach of choice in 96.2% of cases (93.0% percutaneous and 3.2% surgical). The nontransfemoral access routes chosen were the subclavian (2.2%) and, rarely, the transapical approach (<1%). The type of valve most frequently implanted in the 3904 cases with this information was the balloon expandable (1707, 43.7%) (Edwards Lifesciences, United States), followed by the Evolut self-expanding valve (1341, 34.3%) (Medtronic, United States) and the self-expanding Acurate Neo (406, 10.4%) (Boston Scientific, United States). Other valves implanted with lower frequency were Portico (293, 7.5%) (Abbott Vascular, United States) and, in lower numbers, Lotus (Boston Scientific), MyVal (Meril, India), and Allegra (Biosensors, Singapore). Regarding the patient profile, most patients (65.5%) were older than 80 years.

Mitral and tricuspid valve interventionsIn 2020, the downward trend in mitral valvuloplasties became consolidated; this trend has been evident since 2011. Overall, 164 procedures were performed in Spain, fewer than half that in 2011.

In addition, 31 prostheses were percutaneously implanted in the mitral position (most within the annulus or a failed bioprosthesis), which was more than double the number of previous years.

Despite the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, there was significant growth in percutaneous mitral valve repair with the edge-to-edge clip technique. In total, 438 procedures were performed vs 385 in 2019 (a 14% increase); a total of 596 clips were implanted (giving a clip/procedure ratio of 1.4, which indicates no change vs 2019; 64% of procedures involved a single clip). Secondary mitral regurgitation was the most commonly treated etiology (50.1%), followed by degenerative (36.6%) and mixed (13.2%).

Tricuspid valve activity was still limited, although there was a notable increase vs 2019. Thus, 15 TAVIs were performed in the tricuspid position, 46 valves in the bicaval heterotopic position (6 in 2019 and 2 in 2018), and 37 clip repairs (18 in 2019).

Nonvalvular structural interventionsLeft atrial appendage closure, which grew by 43% in 2019, fell by 8% in 2020, dropping to 845 procedures. Of these, 489 patients used the Amulet device (Abbott Vascular, United States), 313 used the Watchman (Boston Scientific, United States), and 132 used the LAmbre (Lifetech Scientific, United States), which was the only device showing growth (38% vs 2019).

In total, 186 patients underwent paravalvular leak treatment (203 in 2019); there was a minute increase in the closure of mitral leaks (113 in 2019 vs 117 in 2020) and a decrease in that of aortic leaks (90 in 2019 vs 69 in 2020).

Moreover, there were 98 cases of alcohol septal ablation (114 in 2019), 36 coronary fistula occlusions (34 in 2019), 25 endovascular aortic repairs (50 in 2019), 18 renal denervations (39 in 2019), 17 pulmonary vein dilatations (11 in 2019), 16 coronary sinus reducers (9 in 2019), 13 interatrial shunts (9 in 2019), and 74 balloon pericardiotomies (64 in 2019). In addition, 103 percutaneous procedures were performed to treat pulmonary thromboembolisms in acute cases (vs 133 in 2019), as well as 119 in chronic cases (vs 162 in 2019).

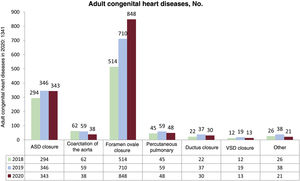

Interventions in adult congenital heart diseaseA total of 1341 procedures were performed in adult congenital heart diseases. This represented a 5.8% increase vs 2019, largely due to patent foramen ovale closure, which was the only procedure showing growth, with 848 cases (710 in 2019 and 514 in 2018) (figure 7). The other procedures fell vs previous years: 343 atrial septal defect closures, 38 aortic coarctation closures, 30 ductal closures, and 13 ventricular septal defects.

DISCUSSIONWe have summarized interventional activity in Spain in 2020, the first year of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (figure 8). The main findings were: a) most procedures showed notably decreased activity in 2020 compared with the upward trend of previous years; b) only patent foramen ovale closure and mitral valve clip repair increased vs previous years (19.4% and 13.8%, respectively); and c) there was once again marked heterogeneity among autonomous communities in the penetrance of treatments with proven prognostic impact, such as primary angioplasty, pressure guidewires, and TAVI.

In previous studies, we showed that, during the first weeks of the lockdown in March and April 2020, some interventional procedures fell markedly, such as primary angioplasty6 and TAVI.12 However, this article is the first to compile the totality of procedures in Spain throughout 2020. Notably, the observed reduction was lower than that described during the first weeks of the first lockdown, which indicates a rebound in activity after the first wave of the pandemic. For example, a recent article reported reductions in PCI of 48% and in structural procedures of 81% in Spain,13 whereas the current registry showed reductions of 10.1% in PCI and of < 1% in TAVI. Among all procedures, those with the steepest falls were diagnostic catheterizations and nonurgent PCIs, at close to 10%. It must be highlighted that, whereas primary angioplasty fell by 4.1%, rescue angioplasty increased, which may reflect greater penetrance of pharmacological reperfusion during the weeks of the worst hospital saturation in the first wave of the pandemic.14

Of the gamut of interventional procedures, those with the greatest falls were certain structural procedures such as TAVI. However, some even increased, such as mitral valve clip repair, tricuspid valve treatment, and patent foramen ovale closure. Of these, patent foramen ovale closure stood out, given that it is a preventive procedure and, thus, not clinically urgent, which suggests the huge growth remaining for this technique based on the latest scientific evidence regarding stroke recurrence prevention.15

A marked heterogeneity in the application of different treatments has become consolidated over the years among the various autonomous communities in Spain. This heterogeneity is particularly significant when it concerns techniques or procedures that are associated with a major prognostic impact and are based on solid scientific evidence. This is the case, for example, with the pressure guidewire16 (figure 2); whereas some autonomous communities such as Navarre, Aragon, Asturias, the Basque Country, and Madrid approach the European average of 1 pressure guidewire for every 5 PCIs, Castile-La Mancha, the Canary Islands, the Balearic Islands, and Andalusia performed less than 1 for every 12 PCIs. The case of TAVI is also particularly striking; severe aortic stenosis is the most frequent valvular heart disease in the adult population, affecting 5% of individuals older than 65 years and showing 97% mortality at 5 years.17 Based on its proven effectiveness in recent studies, clinical practice guidelines award TAVI a strong recommendation.18 Nevertheless, although some Spanish autonomous communities such as Galicia and Cantabria greatly exceeded the European average of 141 TAVIs/million population,17 most were below; this was the case for Aragon and La Rioja in particular, which failed to reach even 50/million.

CONCLUSIONSIn the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry revealed a marked decrease in activity in all procedures, except for percutaneous mitral valve clip repair and patent foramen ovale closure. This fall was lower than previously described, which indicates a rebound in interventional activity after the first wave of the pandemic.

FUNDINGNone.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll authors significantly contributed to the data collection and the critical revision of the manuscript. R. Romaguera, S. Ojeda, I. Cruz-González, and R. Moreno drafted the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

The Steering Committee of the ACI-SEC would like to thank our collaborators for their work and effort, which make this registry possible, particularly given the difficult situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Agustín Guisado Rasco (Hospital Virgen del Rocío), Alejandro Gutiérrez-Barrios (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar), Antonio Gómez-Menchero (Juan Ramón Jiménez Huelva), Francisco José Morales Ponce (Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real), Francisco José Sánchez Burguillos (Hospital Universitario de Valme), Jesús Oneto (Hospital Universitario de Jerez), Juan Caballero Borrego (Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio), Joaquín Sánchez Gila (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves), Juan Antonio Bullones Ramírez (Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga), Juan Carlos Fernández (Hospital Universitario de Jaén), Juan Horacio Alonso Briales (Hospital Virgen de la Victoria), Luis Antonio Íñigo García (Hospital Costa del Sol), Manuel Vizcaíno Arellano (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena), Ricardo Fajardo Molina (Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas), Soledad Ojeda (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía y Hospital Quirónsalud Córdoba), Antonio Ramírez-Moreno (Hospiten Estepona), Javier Suárez de Lezo (Hospital Cruz Roja), Luis Antonio Íñigo García (Hospital Helicópteros Sanitarios), Rafael García-Borbolla Fernández (Viamed Santa Ángela de la Cruz), Santiago Jesús Camacho Freire (Hospital San Agustín), Sara María Ballesteros Pradas (Hospital Quirónsalud Sagrado Corazón), Iñigo Lozano (Hospital de Cabueñes), Pablo Avanzas (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias), María José Bango (Centro Médico de Asturias), Francisco Bosa Ojeda (Hospital Universitario de Canarias), Francisco Manuel Jiménez Cabrera (Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria), Pedro Martin Lorenzo (Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín), Raquel Pimienta González (Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria), Zuheir Kabbani Rihawi (Hospital Universitario Hospiten Rambla), Javier Zueco (Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla), Ignacio Sánchez Pérez (Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real), Jesús Jiménez-Mazuecos (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete), Enrique Novo García (Hospital General Universitario de Guadalajara), José Moreu Burgos (Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo), Armando Pérez de Prado (Hospital Universitario de León), Ignacio Cruz-González (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca), Ignacio J. Amat-Santos (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Hospital Recoletas Campo Grande y Hospital Vithas Vitoria), Javier Robles Alonso (Hospital Universitario de Burgos), Beatriz Vaquerizo (Hospital del Mar), Bruno García del Blanco (Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron y Hospital Dexeus), Eduard Bosch Peligero (Parc Taulí), Gerard Roura (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge), Mohsen Mohandes (Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII), Joan Bassaganyas (Hospital de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta), Juan Manuel Casanova-Sandoval (Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida), Manel Sabaté (Hospital Clínic de Barcelona y Hospital General de Catalunya), Xavier Carrillo Suárez (Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol), Joan García Picart (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau), Juan Francisco Muñoz Camacho (Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa), Julio Carballo Garrido (Centro Médico Teknon), Juan Sanchis (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia), Alberto Berenguer Jofresa (Hospital General de Valencia), Ana María Planas del Viejo (Hospital General Universitario de Castellón), Araceli Frutos García (Hospital Universitario de San Juan de Alicante), Francisco Pomar Domingo (Hospital de la Ribera), Francisco Torres Saura (Hospitales Torrevieja-Salud/Vinalopó Elche), José Luis Díez Gil (Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe), Juan Miguel Ruiz Nodar (Hospital General Universitario de Alicante y Clínica Benidorm), Miguel Jerez Valero (Hospital De Manises), Pablo Aguar (Hospital Dr. Peset), Paula Tejedor (Hospital General Universitario Elche), Ramón López Palop (Hospital Quirónsalud Torrevieja), Vicente Mainar (Hospital IMED Levante), Antonio Merchán Herrera (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz), Javier Fernández Portales (Hospital de Cáceres), Juan Carlos Rama Merchán (Hospital de Mérida), José Antonio Baz (Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro), Ramiro Trillo Nouche (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago), Ramón Calviño Santos (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña), Raymundo Ocaranza (Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti), Gonzalo Peña (Hospital San Rafael A Coruña), Alfredo Gómez Jaume (Hospital Universitario Son Espases y Clínica Juaneda), Armando Bethencourt (Hospital Quirónsalud Palmaplanas), Lucia Vera Pernasetti (Policlínica Ntra. Sra. del Rosario), María Pilar Portero Pérez (Hospital San Pedro), Ángel Sánchez-Recalde (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Zarzuela y Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Moraleja), Fernando Rivero Crespo (Universitario de la Princesa), Fernando Sarnago Cebada (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre), Jaime Elízaga (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón), Juan Antonio Franco Peláez (Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz/Hospital General de Villalba), Juan Francisco Oteo Domínguez (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda), Juan Ruiz García (Hospital Universitario de Torrejón), Lorenzo Hernando Marrupé (Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón), María José Pérez Vizcayno (Hospital Clínico San Carlos), Raúl Moreno (Hospital Universitario La Paz), Rosa Sánchez-Aquino González (Hospital Rey Juan Carlos y Hospital Infanta Elena), Salvador Álvarez Antón (Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla), Belén Rubio Alonso (Quirónsalud Madrid y Complejo Hospitalario Ruber Juan Bravo), Carlos Macaya (Hospital Nuestra Señora del Rosario, Vithas Madrid la Milagrosa y Clínica Nuestra Señora de América), Eduardo Alegría Barrero (Hospital Ruber Internacional), Eulogio García (Hospital HLA Universitario Moncloa), Felipe Hernández Hernández (Clínica Universidad de Navarra (Madrid), Jorge Palazuelos Molinero (Hospital La Luz y Hospital Quirónsalud Sur Alcorcón), Leire Unzué (Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe, Hospital Universitario HM Sanchinarro y Hospital Universitario HM Puerta del Sur), María Eugenia Vázquez Álvarez (Hospital San Rafael-Madrid), Eduardo Pinar Bermúdez (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca y Hospital La Vega Murcia), Francisco Javier Lacunza Ruiz (Hospital Quirónsalud Murcia), Valeriano Ruiz Quevedo (Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra), Miguel Artaiz Urdaci (Clínica Universidad de Navarra de Pamplona), Alfonso Miguel Torres Bosco (Hospital Universitario Araba-Txagorritxu), Asier Subinas Elorriaga (Hospital de Galdakao-Usansolo), Koldobika Garcia San Román (Hospital Universitario de Cruces), Roberto Saez Moreno (Hospital de Basurto), Leire Andraka (Clínica IMQ Zorrotzaurre), Mariano Larman Tellechea (Policlínica Gipuzkoa-Hospital Donostia), José Antonio Diarte de Miguel (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet), and José Ramón Ruiz Arroyo (Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa).

| Autonomous community | Center | Type of center |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | Hospital Virgen del Rocío | Public |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar | Public | |

| Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez Huelva | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario de Valme | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario de Jerez | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio | Public | |

| Hospital Virgen de las Nieves | Public | |

| Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario de Jaén | Public | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Victoria | Public | |

| Hospital Costa del Sol | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía | Public | |

| Hospiten Estepona | Private | |

| Hospital Cruz Roja | Private | |

| Hospital Helicópteros Sanitarios | Private | |

| Viamed Santa Ángela de la Cruz | Private | |

| Hospital San Agustín | Private | |

| Quirón Sagrado Corazón | Private | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Córdoba | Private | |

| Aragon | Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | Public |

| Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa | Public | |

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital de Cabueñes | Public |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias | Public | |

| Centro Médico de Asturias | Private | |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Espases | Public |

| Clínica Juaneda | Private | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Palmaplanas | Private | |

| Hospital Juaneda Miramar | Private | |

| Policlínica Nuestra Señora del Rosario | Private | |

| Canary Islands | Hospital Universitario de Canarias | Public |

| Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria | Public | |

| Hospiten Rambla y Sur | Private | |

| Cantabria | Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla | Public |

| Castile-La Mancha | Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real | Public |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Albacete | Public | |

| General Universitario Guadalajara | Public | |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo | Public | |

| Castile and León | Hospital Universitario de León | Public |

| Hospital Universitario de Salamanca | Public | |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid | Public | |

| Universitario de Burgos | Public | |

| Hospital Recoletas Campo Grande | Private | |

| Catalonia | Hospital del Mar | Public |

| Hospital Vall d’Hebron | Public | |

| Parc Taulí | Public | |

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII | Public | |

| Hospital de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida | Public | |

| Hospital Clínic de Barcelona | Public | |

| Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol | Public | |

| Hospital Dexeus | Private | |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau | Public | |

| Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa | Public | |

| Centro Médico Teknon | Private | |

| Hospital General de Catalunya | Private | |

| Extremadura | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz | Public |

| Hospital Universitario de Cáceres | Public | |

| Hospital de Mérida | Public | |

| Galicia | Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro | Public |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago | Public | |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti | Public | |

| Hospital San Rafael A Coruña | Private | |

| Community of Madrid | Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal | Public |

| Universitario de la Princesa | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre | Public | |

| General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz/Hospital General de Villalba | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario de Torrejón | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón | Public | |

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz | Public | |

| Hospital Rey Juan Carlos | Public | |

| Hospital Infanta Elena | Public | |

| Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Zarzuela | Private | |

| Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Moraleja | Private | |

| Hospital Universitario Quirónsalud Madrid | Private | |

| Complejo Hospitalario Ruber Juan Bravo | Private | |

| Hospital Nuestra Señora del Rosario | Private | |

| Vithas Madrid La Milagrosa | Private | |

| Clínica Nuestra Señora de América | Private | |

| Hospital Ruber Internacional | Private | |

| Hospital HLA Universitario Moncloa | Private | |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra | Private | |

| Hospital La Luz | Private | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Sur Alcorcón | Private | |

| HM CIEC, Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe, Hospital Universitario HM Madrid Norte Sanchinarro, HM CIEC, Hospital Universitario HM Puerta del Sur | Private | |

| Hospital San Rafael-Madrid | Private | |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca | Public |

| Hospital la Vega Murcia | Private | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Murcia | Private | |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra | Public |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra | Private | |

| La Rioja | Hospital San Pedro | Public |

| Valencian Community | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia | Public |

| Hospital General de Valencia | Public | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Castellón | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante | Public | |

| Hospital la Ribera | Public | |

| Hospitales Torrevieja-Salud/Vinalopó Elche | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe | Public | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Alicante | Public | |

| Hospital de Manises | Public | |

| Hospital Dr. Peset | Public | |

| Hospital General Universitario Elche | Public | |

| Clínica Benidorm | Private | |

| Hospital Quirón Torrevieja | Private | |

| Hospital IMED Levante | Private | |

| Basque Country | Hospital Universitario Araba-Txagorritxu | Public |

| Hospital de Galdakao-Usansolo | Public | |

| Hospital Universitario de Cruces | Public | |

| Hospital de Basurto | Public | |

| Vithas Hospital Vitoria | Private | |

| Clínica IMQ Zorrotzaurre | Private | |

| Policlínica Gipuzkoa-Hospital Donostia | Public |