We report the results of the 2023 Spanish catheter ablation registry.

MethodsProcedural data were collected and incorporated into the REDCap platform by all participating centers through a specific form.

ResultsThere were 104 participating centers in 2023 compared with 103 in 2022. In 2023, the total number of ablation procedures was 26 207, indicating a stabilization of the increase observed in 2022 following the pandemic. The increase was mainly due to procedures for atrial fibrillation (AF), with a total of 9942 ablations, representing 38% of all substrates. Notably, pulse-field ablation represented 10.3% of all AF ablation procedures, leading single-shot ablation strategies to outnumber point-by-point AF ablation for the first time in the history of the registry. Cavotricuspid isthmus ablation remained the second most targeted substrate (19% of all substrates, n=5067). The overall acute success rate remained high (97%), with a downward trend in the complication rate (1.6% vs 1.8% in 2022) and mortality rate (0.03%; n=7). Compared with 2022, there was a significant increase in procedures performed using electro-anatomical mapping and zero-fluoroscopy techniques for cavotricuspid isthmus ablation (52% vs 26%), AV node re-entrant tachycardia (48% vs 34%), and accessory pathways (62% vs 22%). We registered 466 ablations in pediatric patients.

ConclusionsThe data indicate a stabilization in the post-pandemic increase in ablation procedures, with an absolute and relative increase in AF as the predominant substrate. Success rates remained stable with a modest reduction in complication and mortality rates.

Keywords

The Spanish catheter ablation registry has been systematically collecting data on the activity and resources of arrhythmia units in Spain for more than 2 decades. The present document comprises the latest official registry report of the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC). This report outlines the changes over time in the interventional management of cardiac arrhythmias in Spain.1–22 The objective is to provide pertinent information on each of the ablation techniques used, the available technology, and the human resources in the Spanish health care system. Finally, the document provides the data on the safety and effectiveness of each ablation target.

METHODSThe present work involves a retrospective registry of the activity of electrophysiology laboratories in Spain in 2023. Data were voluntarily obtained from participating centers using a standardized form available on the REDCap online platform, which is part of the recording platform of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC. The registry is continuously compiled, updated, and maintained throughout the year with the collaboration of a team consisting of full members of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC, as well as the technical team and coordinator of the Heart Rhythm Association registries of the SEC. The device manufacturing and marketing industry also collaborates by providing relevant data. All members contributed to data cleaning and analysis and are responsible for this publication. The data were re anonymized for the authors of the present report.

Information was collected on the specific technical and human resources of the participating arrhythmia units, the ablation technique and modality, and the type of ablation target treated, as well as the ablation outcomes and complications. Eleven ablation targets were analyzed: atrial fibrillation (AF), cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI), atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT), accessory pathway (AP), atrioventricular node (AVN), macrore-entrant atrial tachycardia (MAT), focal atrial tachycardia (FAT), idiopathic ventricular tachycardia (IVT), ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia (ICM-VT), nonischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia (NICM-VT), and cardioneuroablation.

The following variables were analyzed: the number of patients and procedures (specifying the number of pediatric patients, defined as those younger than 15 years), acute success (at the end of the procedure), the type of ablation catheter used, and the number and type of in-hospital complications. Periprocedural mortality data were also recorded. The data collection permitted the inclusion of specific details on certain ablation targets (eg, vein of Marshall ethanol infusion in AF and MAT, as well as scar type and location in nonischemic cardiomyopathies). Also recorded were the use of electroanatomic mapping systems and the number of zero-fluoroscopy procedures.

RESULTSTechnical and human resourcesThe technical and human resources of the participating laboratories, as well as the other procedures (in addition to ablation) performed by the arrhythmia units, are detailed in table 1.

Variations in human resources in Spanish electrophysiology laboratories from 2014 to 2023

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff physicians | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.7 |

| Full-time physicians | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| Fellows/y | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| RNs | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| RTs | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

RN, registered nurse; RT, radiologic technologist.

Values represent means.

The mean number of physicians per laboratory increased again to 3.7±1.4, while the number of full-time physicians per arrhythmia unit was 2.6±1.8 (table 1). The percentage of centers with at least 1 full-time electrophysiologist remained at 81%. Nursing staff numbers were stable, with an average of 3.4±1.9 nurses per unit. The percentage of centers with a training program for fellows was also stable at about 40% (37% in 2023), generally with 1 or 2 fellows per center (0.6±1.1).

Most centers (69%) were equipped with at least 1 dedicated cardiac electrophysiology laboratory. The number of centers with 2 dedicated laboratories continued its slow increase (27 centers in 2023 vs 24 in 2022) while 1 center had 3 available laboratories, as in 2022. Once again, laboratories were available on 3.8±2 days a week (median, 5).

Eleven centers (10.6%) had no electroanatomic mapping system, and the number of centers with at least 2 such systems was 51 (49%), which is similar to the figure recorded in 2022. The most common electroanatomic mapping systems were Ensite and Carto. Almost half of the centers (n=51; 49%) were equipped with intracardiac echocardiography. Of the alternative energy sources to radiofrequency, cryoablation was available in a similar percentage of centers as in 2022 (80% vs 79% in 2022). No laser ablations were reported. Finally, both electroporation (pulse-field ablation [PFA], 14% of centers) and cardioneuroablation (41% of centers) showed a notable increase. Regarding procedures other than ablation, most centers implanted pacemakers, defibrillators, cardiac resynchronization devices, and Holter monitors, with percentages exceeding 90% in all centers. The percentage of centers performing left atrial appendage closure remained at about 20%.

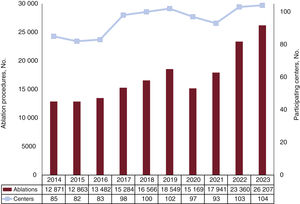

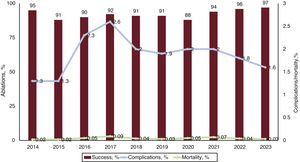

Overall resultsThere was a moderation in the increase in the number of ablations in 2023 vs the marked growth recorded in 2022, following 2 years of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (2020 and 2021). A total of 26 207 ablations were recorded, compared with 23 360 in 2022, with only 1 new center joining the registry (figure 1). The distribution of participating centers between private and publicly funded was very similar to that of previous years (74 publicly funded and 30 private).

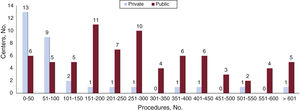

The median number of ablations per center was 202 [interquartile range, 308.5]. The number of centers performing a high number of ablations increased considerably, with the number of centers conducting more than 600 ablations per year rising from 3 to 6 in just 1 year (5 of these centers were publicly funded) (figure 2). In addition, there was a marked increase in private centers performing high numbers of ablations. For example, the number of private centers performing between 51 and 100 ablations (a 50% increase in this range) rose from 6 to 9, due to a corresponding decrease in centers performing fewer than 50 ablations per year.

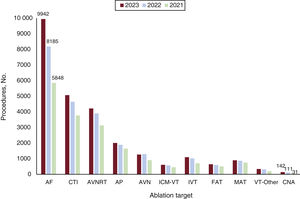

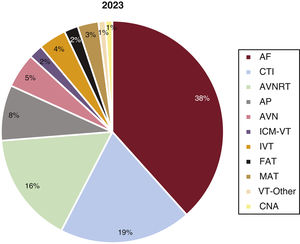

The distribution of ablation targets treated was similar to that of previous years, with an increase in the predominant ablation target AF both in absolute numbers (from 8185 to 9942 ablations) and relative terms (from 35% to 38% vs the other ablation targets) (figure 3 and figure 4). There was also a sharp increase in cardioneuroablation procedures, particularly in the number of centers treating this ablation target. AP ablation continued its downward trend vs the other ablation targets, decreasing from 9% to 8% in 2023.

Distribution of the number of procedures per ablation target and year. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia; CNA, cardioneuroablation; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; ICM-VT, ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macrore-entrant atrial tachycardia; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Relative proportions of ablation targets in 2023. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AT, atrial tachycardia (focal and atypical flutter); AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia; CNA, cardioneuroablation; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

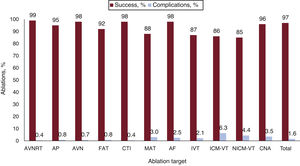

The overall acute procedural success rate slightly increased, from 96% to 97%, and the complication rate fell again (1.6% vs 1.8% in 2022), as did mortality (0.03%), to levels similar to those of a decade ago (figure 5). Regarding effectiveness and complication rates by ablation target, the complication rate for VT ablations improved for both idiopathic VT and VT with underlying heart disease (figure 6). Complications associated with AF ablation fell from 2.8% (in 2022) to 2.5%.

Variations in success and complication rates per ablation target in 2023. AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia; CNA, cardioneuroablation; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; ICM-VT, ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macrore-entrant atrial tachycardia; NICM-VT, nonischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia. Values represent percentages.

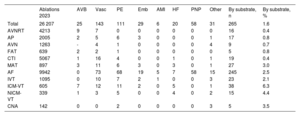

A total of 419 complications were recorded. Vascular complications were once again the most frequent (n=143), followed by pericardial effusion (n=111). The distribution of complications by ablation target is presented in table 2. There were 7 procedure-related deaths, vs 10 in 2022 (0.03%); 3 of these deaths were in patients with AF (2 due to massive stroke and 1 due to refractory shock) while the remaining 4 were in patients undergoing VT ablation. The following sections detail the results for each ablation target.

Complications recorded by ablation target in 2023

| Ablations 2023 | AVB | Vasc | PE | Emb | AMI | HF | PNP | Other | By substrate, n | By substrate, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 26 207 | 25 | 143 | 111 | 29 | 6 | 20 | 58 | 31 | 265 | 1.6 |

| AVNRT | 4213 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0.4 |

| AP | 2005 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 0.8 |

| AVN | 1263 | - | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 0.7 |

| FAT | 639 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.8 |

| CTI | 5067 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 19 | 0.4 |

| MAT | 897 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 27 | 3.0 |

| AF | 9942 | 0 | 73 | 68 | 19 | 5 | 7 | 58 | 15 | 245 | 2.5 |

| IVT | 1095 | 0 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 23 | 2.1 |

| ICM-VT | 605 | 7 | 12 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 38 | 6.3 |

| NICM-VT | 339 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 4.4 |

| CNA | 142 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3.5 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AP, accessory pathway; AVB, atrioventricular block; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia; CNA, cardioneuroablation; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; Emb, embolism; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; HF, heart failure; ICM-VT, ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macrore-entrant atrial tachycardia; NICM-VT, nonischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia; PE, pericardial effusion; PNP, phrenic nerve palsy; Vasc, vascular complications.

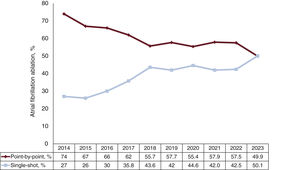

Once again, AF ablation remained the most commonly treated ablation target and even increased, with a total of 9942 procedures (1757 more than in 2022). This ablation target was treated in 89% of the centers participating in the registry (2 percentage points higher than in 2022). Regarding clinical presentation, 60.3% of cases were paroxysmal AF, 35.7% were persistent AF, and 4% were long-standing persistent AF. These percentages are similar to those of previous years. The overwhelming majority of ablation procedures involved electrical isolation of the pulmonary veins (n=9240), followed by electrogram reduction at the pulmonary vein antrum (n=957) and lines in the left atrium (n=633). Other ablation targets included superior vena cava isolation (n=83), fibrotic area ablation (n=122), and vein of Marshall ethanol infusion (n=174). Reported success rates were 97% for pulmonary vein isolation and 99% for superior vena cava isolation.

Defining single-shot as the only other single-shot ablation strategy besides point-by-point ablation, a combined single-shot plus point-by-point strategy was used in 89 patients, out of a total of 9942 AF ablation procedures. For the first time in the registry, the single-shot technique (50.1% of AF ablations) exceeded the point-by-point approach (49.9%) (figure 7). The point-by-point techniques included irrigated-tip catheters with contact forcesensing technology in 4775 procedures, standard irrigated catheters in 352 procedures, and other types in 56 procedures. Among the single-shot techniques, cryoablation continued to predominate (n=3954 procedures), although there was a highly significant increase in PFA (n=1038 procedures), which sharply increased from 3% of all AF ablation procedures in 2022 to 10.3% in 2023. Mapping systems were used in 5078 procedures (51%), and zero-fluoroscopy procedures comprised 530 (5.3%). As auxiliary instruments for ablation, steerable sheaths were used in 2683 procedures, intracardiac echocardiography in 1057, and general anesthesia in 4511.

In 2023, a total of 245 complications were recorded. This figure corresponded to 2.5% and is slightly lower than the 2.8% recorded in 2022. The most common complications were vascular (29%), followed by pericardial effusion (27%) and phrenic nerve palsy (24%). Less frequent complications included peripheral embolism (7.6%) and heart failure/shock (2.8%). Three deaths were reported (6 in 2022): 2 due to massive stroke and 1 due to cardiogenic shock. No cases of AF ablation-related atrioesophageal fistula were reported in 2023.

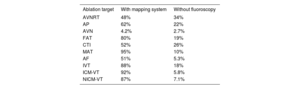

Cavotricuspid isthmusA total of 5067 CTI ablations were recorded in 2023 (427 more than in 2022). As a result, CTI was the second most commonly treated ablation target after AF (19.5% of all ablations). The trend continued toward an increased number of procedures performed with a mapping system (14% increase from 2022) and without fluoroscopy (7% increase from 2022) (table 3).

Use of electroanatomic mapping systems and zero-fluoroscopy procedures by ablation target in 2023

| Ablation target | With mapping system | Without fluoroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| AVNRT | 48% | 34% |

| AP | 62% | 22% |

| AVN | 4.2% | 2.7% |

| FAT | 80% | 19% |

| CTI | 52% | 26% |

| MAT | 95% | 10% |

| AF | 51% | 5.3% |

| IVT | 88% | 18% |

| ICM-VT | 92% | 5.8% |

| NICM-VT | 87% | 7.1% |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AP, accessory pathway; AVN, atrioventricular node; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; ICM-VT, ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; NICM-VT, nonischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macrore-entrant atrial tachycardia.

The success rate was 98% (similar to 2022), with a similar percentage of complications vs the previous year (0.5% in 2022 and 0.4% in 2023). Most complications were vascular (n=16) and 1 patient developed atrioventricular block (AVB). The most commonly used catheters were irrigated-tip catheters with contact forcesensing technology (41%), followed by standard irrigated catheters (31%) and 8- and 4-mm catheters (23% and 5%, respectively).

Atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardiaAVNRT ablation continued to be the third most commonly treated ablation target (16%), after AF and CTI. Although the percentage relative to other ablation targets has gradually decreased in recent years, the absolute number of procedures has progressively increased (4213 procedures, representing an 8% increase vs 2022). The reported success rate was 99%, with a complication rate of 0.4%, which included 9 AVBs (0.2%) and 7 vascular complications. Both the energy source used (radiofrequency was the most frequently used approach, while cryoablation was used in only 2.2% of procedures) and the use of mapping systems (48%) remained at figures similar to those of previous years.

Accessory pathwaysAP ablation was once again the fourth most frequently treated ablation target, accounting for 8% of all ablations performed and showing a 6.2% increase in the total number of procedures vs 2022 (2005 vs 1888 in 2022). The success rate was 95% while the complication rate was 0.8%, which included 6 pericardial effusions, 5 vascular complications, 3 embolisms, and 2 AVBs. In addition, 46% of the APs showed bidirectional conduction, 19% had exclusively anterograde conduction, and 35% had exclusively retrograde conduction. Left APs continued to be the most frequent location (52.5% of procedures, with a 98% ablation success rate), followed by inferoseptal pathways (26.5%; 97% success rate), para-Hisian/anteroseptal pathways (10.6%; 80% success rate), and right free wall pathways (10.5%; 93% success rate). Epicardial ablation was necessary in 28 procedures. Transseptal access was used more frequently than retroaortic access for ablation of the left pathways (61% vs 39%). Mapping systems were used in more than half of all procedures and almost a fifth were fluoroscopy-free.

Atrioventricular node ablationA total of 1263 AVN ablations were performed in 2023 (30 fewer than in 2022). A success rate of 98% was recorded, as well as a complication rate of 0.3% (all vascular). The most commonly used catheters were 4-mm catheters (47%), followed by standard irrigated catheters (28%) and 8-mm and irrigated contact forcesensing catheters (19% and 6%, respectively). Mapping systems and zero-fluoroscopy strategies were used in less than 5% of all procedures for this ablation target.

Macrore-entrant atrial tachycardiaIn 2023, 897 procedures were performed for this ablation target (35 more than in 2022). This figure represented 3.5% of all ablations in the registry. Overall effectiveness remained similar to that of 2022 (88% in 2022 and 89% in 2023) for both right atrial ablation targets (88%) and left atrial targets (91%). Most catheters (89%) were contact forcesensing catheters. There was a notable increase in the use of electroporation (n=5) and vein of Marshall ethanol infusion (n=18), although the number of procedures is still very low.

All procedures were performed using a mapping system, and 90 were performed without fluoroscopy. Of the 21 complications reported, the most frequent were vascular (n=11), followed by pericardial effusions requiring drainage (n=6) and embolic phenomena (n=3). As for AF ablation, no atrioesophageal fistula was reported after MAT ablation in 2023.

Focal atrial tachycardiaIn 2023, 639 FAT ablations were performed (47 more than in 2022), representing 2.5% of all reported ablations. Of these, 65% were in the right atrium and 35% in the left atrium, with acute success rates of 95% and 89%, respectively (similar to 2022). Five complications were recorded: 2 AVBs requiring pacemaker implantation, 2 vascular complications, and 1 pericardial effusion. All procedures were performed using a mapping system, while 124 were conducted without fluoroscopy.

Idiopathic ventricular tachycardiaIVT ablation procedures in 2023 remained consistent with 2022, both as a percentage (4.2%) and in absolute numbers (1095 vs 1011 procedures in 2022). The number of centers performing these procedures was also stable, at 85, with a median of 8.5 [12] procedures per center. Regarding the locations of the tachycardias, 47% originated in the right ventricular outflow tract, 20% in the left ventricular outflow tract, and 13% in the aortic root. In addition, 6.4% were fascicular tachycardias, 3% were epicardial tachycardias, and 0.1% originated in the pulmonary artery. In 10% of procedures, the origin was located elsewhere (from most to least frequent): papillary muscle, mitral annulus, tricuspid annulus, and moderator band. The reported success rate was 87% (72% in the left ventricular outflow tract and 91% in the right ventricular outflow tract).

Mapping systems were used in 90% of procedures. The use of irrigated-tip catheters with contact forcesensing technology was standard for this ablation target (89%). The use of energy sources other than radiofrequency was rare (alcohol ablation in 3 cases and cryoablation in 2). Overall, 23 complications were recorded (2.1%), including 10 vascular complications, 7 pericardial effusions, 2 embolisms, 1 acute infarction, and 1 aortic leaflet perforation. One death occurred, caused by electromechanical dissociation in the context of arterial ethanol ablation.

Ischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardiaAlthough there were no major changes in the number of centers performing ICM-VT ablations (n=70) or the percentage of procedures (2% of the total number of ablations performed), there was an absolute increase of 6.7% in the number of procedures (n=605). The median number of procedures was 5 [8]. Mapping systems were used in most procedures, and zero-fluoroscopy procedures were rare (table 3). The acute success rate was 86% and the most commonly used ablation catheters were irrigated-tip catheters with contact forcesensing technology (97%). Six centers performed stereotactic radioablation (18 procedures). The access routes were similar to those used in 2022, with transseptal access being the common (66% of procedures). A combined endocardial/epicardial approach was used in 9% of procedures, while exclusively epicardial access was used in 2.6%. The predominant strategy was substrate ablation (68%), with conventional activation mapping applied in 18%. The complication rate was 6.3%, which is similar to that of previous years, and included 12 vascular complications, 7 AVBs, 11 pericardial effusions, 2 embolisms, and 5 cases of heart failure decompensation. Three deaths were associated with the procedure (1 electromechanical dissociation, 1 stroke, and 1 cardiogenic shock; 0.5% mortality).

Nonischemic cardiomyopathy ventricular tachycardiaThe number of centers (n=59) and total number of procedures (n=339) in 2023 were similar to those in 2022. The median number of procedures per center was 2 [19] and the success rate was 85%. An electroanatomic mapping system was used in most procedures (87%). The main ablation targets were nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy in 183 procedures (54%; 79% success), arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy in 59 procedures (17%; 76% success), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in 14 procedures (4.1%; 100% success), congenital heart disease in 30 procedures (8.8%, 93.3% success), and bundle-branch tachycardia in 9 procedures (2.6%; 87.5% success).

The use of irrigated-tip catheters with contact forcesensing technology was standard (95.5%), while the use of other energy sources was rare, with 9 radioablations and 1 alcohol ablation. The transseptal approach was used in 37% of procedures. A combined endocardial-epicardial approach was used in 22% of procedures while exclusively epicardial access was used in 13%.

The reported complication rate was 4.4%: 5 pericardial effusions, 4 heart failure decompensations, 3 vascular complications, and 1 pleural effusion. No deaths were associated with the procedure.

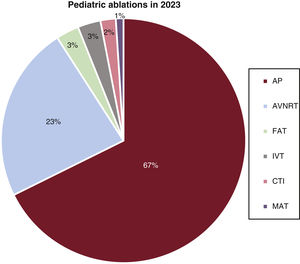

Ablations in pediatric patientsA total of 466 ablations were reported in pediatric patients, representing 3.3% of the total figure, without counting AF or VT ablations (including these ablation targets, the percentage of the total was 1.8%) (figure 8). The most frequently treated ablation target continued to be APs (67% of procedures, 313 procedures, 41 centers), followed by AVNRT (23%, 109 procedures, 29 centers) and FAT (3.4%, 16 procedures, 12 centers). Other ablation targets were much less frequently treated in this population: IVT (3.4%), ICT (1.5%), MAT (1%), NICM-VT (2 procedures), and AF (1 procedure). Thus far, no complications have been associated with ablations performed in the pediatric population.

Relative proportion of each ablation target in pediatric patients (younger than 15 years) vs the total number of procedures in 2023. AP, accessory pathway; AVNRT, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; FAT, focal atrial tachycardia; IVT, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia; MAT, macrore-entrant atrial tachycardia.

The percentage of ablation procedures performed with electroanatomic mapping systems was similar to that of 2022 (55% in 2022 and 54% in 2023). Notably, the use of mapping systems predominated in less complex ablation targets (CTI, AVNRT, and APs), which once again showed an increase in zero-fluoroscopy procedures (table 3). AVN ablation continued to be a less complex target that rarely involved mapping systems and zero-fluoroscopy strategies. The use of mapping systems is practically standard in MAT and VT ablations. For these targets, zero-fluoroscopy procedures are rare, although 18% of IVT ablations adopted a zero-fluoroscopy strategy. Finally, 20% of FAT ablations were performed without a mapping system.

CardioneuroablationIn 2023, there was a significant increase in the number of centers performing cardioneuroablation, rising from 25 centers in 2022 to 41 in 2023. However, the increase in the total number of procedures for this ablation target was more modest (111 in 2022 to 142 in 2023). This indicates that the technique is becoming more established, although the indication for this type of ablation remains limited, likely due to strict patient selection.

DISCUSSIONThe data from the Spanish catheter ablation registry for 2023 indicate a strong recovery in activity after the marked fall in the number of procedures in 2020 and 2021 due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In addition, only 2 years after its introduction, the REDCap online platform has been proven to effectively enable the responsible person in each center to submit data to the registry. Compared with the previous data collection method, the current approach allows for quicker data inclusion, minimizes errors, and provides the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC with an opportunity to use the data for strategic and scientific purposes, while ensuring the impartial and anonymous use of the information gathered.

The absolute number of procedures supports the growth detected in the prepandemic years (figure 1) and even highlights a notable increase both in absolute and relative terms in AF as the predominant ablation target: AF now accounts for almost 40% (specifically, 38%) of all ablation procedures performed in the Spanish healthcare system. The number of participating centers has stabilized at around 100 (n=104), allowing for a comparison with the data from 2022 and reinforcing the validity of the estimated growth in activity (particularly in AF ablation) in the arrhythmia units compared with the previous year.22

For the first time, the absolute number of single-shot techniques has exceeded point-by-point procedures. This trend, driven largely by cryoablation over the years, has finally been confirmed by the rapid rise of PFA as the technique of choice for AF ablation, with a notable increase in its use in just1 year, from 3% to 10.3%. It is likely that PFA will become one of the predominant single-shot techniques in the coming years. It will be interesting to observe whether this shift leads to a decline in the use of point-by-point radiofrequency catheter procedures, cryoablation, or both.

CTI and AVNRT ablation remained the second and third most common procedures, respectively. One noteworthy aspect of these 2 ablation targets is the growing number of procedures performed using a mapping system and without fluoroscopy.

AP ablation exhibited a slow decline, particularly in relative terms, now representing less than 10% of all ablations (8%). The remaining ablation targets remained largely unchanged.

Cardioneuroablation, first incorporated into the registry in 2021, continued to grow, not only in the number of procedures (from 111 in 2022 to 142 in 2023) but also in the number of centers performing it (from 25 to 41), suggesting the technique is becoming more established, despite its use being restricted to highly selected patients.

The overall procedural success rate in 2023 was comparable to that of the previous year (97% in 2023 vs. 96% in 2022). More notably, there has been a progressive reduction in the complication rate, approaching levels recorded a decade ago, when complex ablation targets were less common (eg, in 2014, AF ablation represented less than 20% of ablations vs the other targets).13 The complication rate has fallen to 1.6% (vs 1.8% in 2022), with a mortality rate of 0.03% (7 cases).

In terms of novel ablation strategies, alongside the increased use of PFA and cardioneuroablation, the use of mapping systems for less complex ablation targets is also becoming more established, with a corresponding increase in zero-fluoroscopy procedures. Growth was also recorded in the use of vein of Marshall ethanol infusion for the treatment of MAT and in substrate ablation for patients with AF. The number of pediatric ablations remained stable.

LimitationsThe present data come from a voluntary registry and are therefore subject to the limitations inherent in this type of report, including its retrospective nature and the inability to statistically compare the data with those from previous years.

CONCLUSIONSThe post-SARS-CoV-2 pandemic increase in activity stabilized in 2023. Registry participation remained steady, reaching a historic peak of 104 participating centers. AF continued its upward trend as the predominant ablation target in both absolute and relative terms compared with other targets, with the notable emergence of PFA. This technique appears to have become established as the leading single-shot method, surpassing point-by-point ablation, despite the increasing complexity of AF ablation strategies. The acute success rate of procedures remains very high (97%), with a sustained decline in complication rates (1.6%) and mortality (0.03%).

FUNDINGNo funding was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSBoth the primary author, V. Bazan, and the coauthors, E. Arana, J.M. Rubio-Campal, and D. Calvo, have fully contributed both to the design of the study and to the data analysis, manuscript drafting, and manuscript revision. D. Calvo is registry coordinator for the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

The coordinators of the registry would once again like to thank all of the participants in the Spanish catheter ablation registry, whose selfless help every year permit the publication of this document. We thank the technical team of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC, the staff of the SEC (Gonzalo Justes, Miguel Salas, Israel García, and Jesús de la Torre) for their outstanding work in data collection and organization, and the other members of the Information Technology and Communication department of the SEC.

| Center | Collaborator |

|---|---|

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria, Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Luis Álvarez Acosta |

| Hospital San Juan de Dios, Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Julio Hernández Afonso |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra | Pablo Ramos Ardanaz |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia | Pablo Peñafiel Verdú |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz | Lucas R. Cano Calabria |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga | Alberto Barrera Cordero |

| Hospital QuirónSalud, Málaga | Alberto Barrera Cordero |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Marbella, Málaga | Alberto Barrera Cordero |

| Hospital Vithas Málaga, Málaga | Alberto Barrera Cordero |

| Hospital Vithas Xanit Internacional Benalmádena, Málaga | Alberto Barrera Cordero |

| Hospital Vithas Sevilla, Seville | Ernesto Díaz Infante/Rocío Cózar León |

| Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid | Vanesa Cristina Lozano Granero |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña | José Luis Martínez Sande |

| Hospital Universitario Dexeus, Barcelona | Àngel Moya Mitjans |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Cantabria | Felipe Rodríguez Entem |

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid | Ricardo Salgado Aranda |

| Hospital Severo Ochoa, Leganés, Madrid | Ricardo Salgado Aranda |

| Hospital Universitario Santa Lucía, Cartagena, Murcia | Ignacio Gil Ortega |

| Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo, Pontevedra | Pilar Cabanas Grandío |

| Hospital Universitario de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra | Óscar Alcalde Rodriguez |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos, Burgos | Francisco Javier García Fernández |

| Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Esplugues de Llobregat, Barcelona | Georgia Sarquella-Brugada |

| Hospital Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Majadahonda, Madrid | Víctor Castro Urda |

| Hospital Universitario de León, León | María Luisa Fidalgo Andrés |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz, Badajoz | J. Manuel Durán Guerrero |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba | Francisco Mazuelos Bellido |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Alcorcón, Madrid | Jose Amador Rubio Caballero |

| Hospital Universitario General de Castellón, Castellón | Víctor Pérez Roselló |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza | Mercedes Cabrera Ramos |

| Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid | José Manuel Rubio Campal |

| Hospital Universitario General de Villalba, Collado Villalba, Madrid | José Manuel Rubio Campal |

| Clínica Sagrada Família, Barcelona | Andreu Porta Sánchez |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete, Albacete | Víctor M. Hidalgo Olivares |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias | José Manuel Rubín López |

| Hospital del Mar, Barcelona | Jesús Jiménez López |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca, Baleares | Carlos Eugenio Grande Morales |

| QuirónSalud Sagrado Corazón, Seville | Juan Manuel Fernández Gómez |

| Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca | Javier Jiménez Candil |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Infanta Luisa, Seville | Rafael Moreno Garrido |

| Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva | María Teresa Moraleda Salas |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid | Daniel Rodríguez Muñoz |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña | Iván Vázquez Esmorís |

| Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, Alicante | José Luis Ibáñez Criado |

| Clínica HLA Vistahermosa, Alicante | Alicia Ibáñez Criado |

| Hospital de Basurto, Bilbao, Vizcaya | María Fe Arcocha Torres |

| Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville | Pablo Bastos Amador |

| Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti, Lugo | Juliana Elices Teja |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme, Seville | Ricardo Pavón Jiménez |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada | Miguel Álvarez López |

| Unidad Funcional Territorial de Electrofisiología Camp de Tarragona, Tarragona | Gabriel Martín Sánchez |

| Hospital La Luz, Madrid | Juan Benezet Mazuecos |

| Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos, Móstoles, Madrid | Federico Gómez Pulido |

| Clínica HLA Santa Isabel, Seville | Alvaro Arce León |

| Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia | Aurelio Quesada Dorador |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas | Haridian Mendoza Lemes |

| Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid | Benito Herreros Guilarte |

| Hospital Universitario La Fe, Valencia | Joaquín Osca Asensi |

| Hospital Universitario QuirónSalud Madrid, Madrid | Tomás Datino Romaniega |

| Complejo Hospitalario Ruber Juan Bravo (equipo Dr. Datino), Madrid | Tomás Datino Romaniega |

| Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Barcelona | Axel Sarrias |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Canarias, Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Julio Jesús Ferrer Hita |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio, Granada | José Miguel Lozano Herrera |

| Hospital Universitario de Toledo, Toledo | Miguel Ángel Arias |

| Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona | Nuria Rivas Gandara |

| Hospital San Pedro La Rioja, Logroño | Pepa Sánchez Borque |

| Hospital Universitario de Álava, Vitoria | Enrique García Cuenca |

| Hospital Universitario de la Ribera, Alzira, Valencia | Bruno Bochard Villanueva |

| Hospital de Manises, Manises, Valencia | Pau Alonso Fernández |

| Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias | Irene Valverde André |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Huelva, Huelva | María Teresa Moraleda Salas |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid | María de Gracia Sandín Fuentes |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid | Agustín Pastor Fuentes |

| Hospital de Cáceres, Cáceres | Javier Portales Fernández |

| Hospital Perpetuo Socorro, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | Pablo M. Ruiz Hernández |

| Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona | Eduard Guasch Casany |

| Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Seville | Alonso Pedrote |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza | Antonio Asso Abadía |

| Clínica Corachán, Barcelona | Jose Maria Guerra Ramos |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona | Ignasi Anguera |

| Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida | Javier Cantalapierda |

| Hospital de Cruces, Barakaldo, Vizcaya | Íñigo Sainz Godoy |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Valencia | Eloy Domínguez Mafé |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona | Enrique Rodriguez Font |

| Centro Médico Teknon, Barcelona | Julio Martí Almor |

| Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante, San Juan de Alicante, Alicante | José Moreno Arribas |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid | José Luis Merino Llorens |

| Hospital Viamed Santa Elena, Madrid | José Luis Merino Llorens |

| Complejo Hospitalario Ruber Juan Bravo (equipo Dr. Merino), Madrid | José Luis Merino Llorens |

| Hospital Clínica Benidorm, Alicante | Vicente Bertomeu González |

| Hospital Universitari Josep Trueta, Girona | Eva María Benito Martín |

| Hospital HM Modelo, A Coruña | Ignacio Mosquera Pérez |

| Hospital La Inmaculada, Granada | Miguel Álvarez López |

| Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset, Valencia | Antonio Peláez González |

| Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real | Francisco Javier Jiménez Díaz |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Valencia | Assumpció Saurí Ortiz |

| Hospital Universitario Donostia, San Sebastián, Guipúzcoa | Antonio Óscar Luque Lezcano |

| Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | Federico Segura Villalobos |

| Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe, Madrid | Jesús Almendral Garrote |

| Hospital Universitario de Torrejón de Ardoz, Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid | Óscar Salvador Montañés |

| Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias Alcalá de Henares, Madrid | Juan José González Ferrer |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena, Valdemoro, Madrid | Federico Gómez Pulido |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid | Rafael Peinado Peinado |

| Hospital IMED, Valencia | Óscar Fabregat Andrés |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid | Ángel Arenal |

| Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla, Madrid | Sara Moreno |

| Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Zarzuela, Madrid | Álvaro Marco del Castillo |

The complete list of collaborators and participating electrophysiology laboratories is provided in appendix 1.