Randomized trials have shown the efficacy of transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO) in patients aged ≤ 60 years with cryptogenic embolism. We aimed to assess the long-term safety and efficacy of PFO closure in patients aged> 60 years.

MethodsOf 475 consecutive patients with cryptogenic embolism who underwent PFO closure, 90 older patients aged> 60 years (mean, 66±5 years) were compared with 385 younger patients aged ≤ 60 years (mean, 44±10 years).

ResultsOlder patients had a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes; P <.01 for all vs younger patients). There were no differences in periprocedural complications between the 2 groups. During a median follow-up of 8 (4-12) years, there were a total of 17 deaths, all from noncardiovascular causes (7.8% and 2.6% in the older and younger patient groups, respectively; HR, 4.12; 95%CI, 1.56-10.89). Four patients had a recurrent stroke (2.2% and 0.5% in the older and younger patient groups, respectively; HR, 5.08; 95%CI, 0.71-36.2), and 12 patients had a transient ischemic attack (TIA) (3.3% and 2.3% in the older and younger patient groups, respectively; HR, 1.71; 95%CI, 0.46-6.39). There was a trend toward a higher rate of the composite of stroke/TIA in older patients (5.5% vs 2.6%; HR, 2.62; 95%CI, 0.89-7.75; P=.081), which did not persist after adjustment for CVRF (HR, 1.97; 95%CI, 0.59-6.56; P=.269).

ConclusionsIn older patients with cryptogenic embolism, PFO closure was safe and associated with a low rate of ischemic events at long-term. However, older patients exhibited a tendency toward a higher incidence of recurrent stroke/TIA compared with younger patients, likely related to a higher burden of CVRF.

Keywords

In patients with cryptogenic stroke, up to 4 randomized trials and subsequent meta-analyses have recently shown a significant reduction in recurrent ischemic stroke events following percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale (PFO).1–6 All randomized trials but one excluded patients older than 60 years, and a mean patient age of about 50 years was reported in the single randomized trial including older patients.3 Thus, whereas PFO closure has been established as the new gold-standard therapy in young patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO, there are no definite recommendations on the management of patients older than 60 years.7–9 Some studies have shown that older patients with cryptogenic stroke exhibit a much higher prevalence of PFO (compared with patients with stroke of known cause), similar to that in younger populations,10,11 but scarce data exist on acute and mid-term clinical outcomes of older patients undergoing PFO closure.12–16 In addition, no studies to date have specifically focused on the long-term outcomes of patients older than 60 years.

The objective of our study was to evaluate long-term clinical outcomes following transcatheter PFO closure in older (> 60 years) patients with cryptogenic embolism.

METHODSA total of 475 consecutive patients who underwent PFO closure between 2001 and 2018 because of cryptogenic embolism (stroke, transient ischemic attack [TIA], peripheral embolism) were included. A presumptive diagnostic of paradoxical embolism was established by a neurologist after screening including brain magnetic resonance imaging and/or brain computed tomography, 24-hour Holter monitoring, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), and transcarotid Doppler. The diagnosis of PFO was established on the basis of a right to left shunt during TEE examination with agitated saline contrast test with and without Valsalva maneuver. The shunt was classified as small, moderate or large, with or without atrial septal aneurysm.17

The type and size of the implanted device were left to the criteria of the physician performing the procedure. Postprocedural TTE was performed in all patients prior to hospital discharge, typically a few hours after the procedure to confirm device position, evaluate residual shunt, and exclude pericardial effusion. Medical therapy at discharge was (usually) aspirin (indefinitely), and clopidogrel was added in some patients (for 6 months) according to the preference of the physician performing the procedure. Anticoagulation was prescribed in the presence of other medical reasons requiring anticoagulation therapy (pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis). At 1- to 6-months postprocedure, patients had a clinical visit and an echocardiographic (TTE and/or TEE) examination. All procedural and 1- to 6-month follow-up data were prospectively entered into a dedicated database.

Follow-up was ensured by the referral neurologist/cardiologist or the physician performing the PFO closure along with the family physician responsible for the patient, but there was no pre-established timing for the clinical visits during the follow-up period after the 1-year follow-up. The medical records of all patients were reviewed and data on all clinical events and current medications were collected. In addition, a systematic clinical visit or telephone call was conducted in all patients with no follow-up data. Each patient was asked about recurrences of stroke, TIA or peripheral embolism, new hospitalizations (and reason), bleeding, arrhythmias and cardiac events, migraine, and current medications. When an event was suspected on the basis of the questionnaire, the complete medical file of the center taking care of the patient was consulted. The patient's primary care physician and cardiologist/neurologist responsible for the patient were consulted if any further information was needed.

All neurological events (stroke, TIA) were diagnosed by a neurologist and defined according to TOAST criteria.18 All bleeding events were recorded and classified according to the BARC criteria.19

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are reported as No. (%). Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation or median (25th to 75th interquartile range) depending on variable distribution. Group comparisons were analyzed using the Student t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, and chi-square test of Fisher exact test for categorical variables. A propensity score analysis was performed to adjust intergroup (≤ 60 year-old group vs> 60 year-old group group) differences in baseline characteristics. The selected variables were body mass index, smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, pulmonary embolism and antithrombotic treatment, using a logistic regression analysis. Clinical outcomes were compared between groups with the use of proportional hazard models. Further comparisons were performed with the Tukey technique. Clinical event rates were also summarized by using the Kaplan-Meier estimates, and comparisons between groups were performed with the log-rank test. Results were considered significant at the <.05 level. All analyses were conducted using the statistical package SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

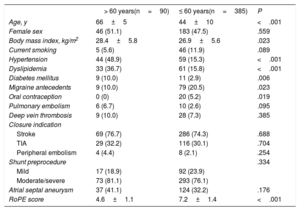

RESULTSBaseline characteristicsOf 475 patients who underwent PFO closure, 90 patients (18.9%) were older than 60 years at the time of the closure (mean age of 66±5 years, vs 44±10 years in the group aged ≤ 60 years). The baseline characteristics of the patients according to age at the time of PFO closure are shown in table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics according to age (> 60 years vs ≤ 60 years)

| > 60 years(n=90) | ≤ 60 years(n=385) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 66±5 | 44±10 | <.001 |

| Female sex | 46 (51.1) | 183 (47.5) | .559 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.4±5.8 | 26.9±5.6 | .023 |

| Current smoking | 5 (5.6) | 46 (11.9) | .089 |

| Hypertension | 44 (48.9) | 59 (15.3) | <.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 33 (36.7) | 61 (15.8) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (10.0) | 11 (2.9) | .006 |

| Migraine antecedents | 9 (10.0) | 79 (20.5) | .023 |

| Oral contraception | 0 (0) | 20 (5.2) | .019 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 6 (6.7) | 10 (2.6) | .095 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 9 (10.0) | 28 (7.3) | .385 |

| Closure indication | |||

| Stroke | 69 (76.7) | 286 (74.3) | .688 |

| TIA | 29 (32.2) | 116 (30.1) | .704 |

| Peripheral embolism | 4 (4.4) | 8 (2.1) | .254 |

| Shunt preprocedure | .334 | ||

| Mild | 17 (18.9) | 92 (23.9) | |

| Moderate/severe | 73 (81.1) | 293 (76.1) | |

| Atrial septal aneurysm | 37 (41.1) | 124 (32.2) | .176 |

| RoPE score | 4.6±1.1 | 7.2±1.4 | <.001 |

RoPE, risk of paradoxical embolism; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Values are reported as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

There were no statistically significant differences between groups in terms of sex, venous thromboembolic disease, current smoking, closure indication, baseline PFO shunt severity, or the presence of atrial septal aneurysm. However, the older group was more likely to have cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and a higher body mass index. Older patients had also a higher risk of paradoxical embolism (RoPE) score.

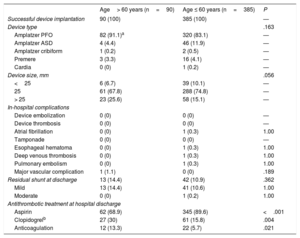

Procedural resultsThere were no statistically significant differences between groups regarding procedural and in-hospital outcomes (table 2). Device implantation was successful in all cases and a similar (low) rate of residual shunt at discharge was observed in both groups. The Amplatzer PFO device (Abbott, Chicago, IL, United States) was used in the vast majority of patients in both groups. Only one episode of atrial fibrillation (AF) post closure occurred in a patient who experienced an esophageal hematoma secondary to the TEE probe in the younger group and who made a full recovery after simple observation. There was a trend toward a bigger device size in the older group.

Procedural characteristics and in-hospital outcomes according to patients’ age

| Age> 60 years (n=90) | Age ≤ 60 years (n=385) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful device implantation | 90 (100) | 385 (100) | — |

| Device type | .163 | ||

| Amplatzer PFO | 82 (91.1)a | 320 (83.1) | — |

| Amplatzer ASD | 4 (4.4) | 46 (11.9) | — |

| Amplatzer cribiform | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | — |

| Premere | 3 (3.3) | 16 (4.1) | — |

| Cardia | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | — |

| Device size, mm | .056 | ||

| <25 | 6 (6.7) | 39 (10.1) | — |

| 25 | 61 (67.8) | 288 (74.8) | — |

| > 25 | 23 (25.6) | 58 (15.1) | — |

| In-hospital complications | |||

| Device embolization | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Device thrombosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Tamponade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Esophageal hematoma | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Major vascular complication | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | .189 |

| Residual shunt at discharge | 13 (14.4) | 42 (10.9) | .362 |

| Mild | 13 (14.4) | 41 (10.6) | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 1.00 |

| Antithrombotic treatment at hospital discharge | |||

| Aspirin | 62 (68.9) | 345 (89.6) | <.001 |

| Clopidogrelb | 27 (30) | 61 (15.8) | .004 |

| Anticoagulation | 12 (13.3) | 22 (5.7) | .021 |

Values are reported as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Regarding antithrombotic therapy at hospital discharge, aspirin was more often prescribed in younger patients, whereas clopidogrel and oral anticoagulation was more frequently prescribed in older participants. Because no patient had AF during the evaluation process, a higher rate of previous pulmonary embolism and peripheral venous thrombosis in the older group (despite nonsignificant differences between groups) may have led to a higher rate of anticoagulation at discharge. After PFO closure, antithrombotic treatment was left to the discretion of the referral neurologist or cardiologist. Finally, there were no reasons other than PFO closure to prescribe dual antiplatelet therapy in some patients.

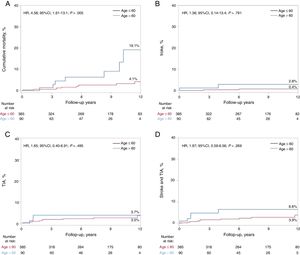

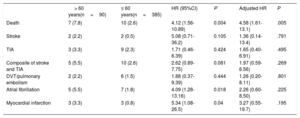

Follow-upThe median follow-up of the entire study population was 8 (4-12) years. Follow-up was complete in all patients except 21 (4.4%, lost to follow-up; 19 [4.9%] and 2 [2.2%] patients in the younger and older patient groups, respectively), leading to a total of 366 and 88 patients with complete follow-up in the younger and older patient groups, respectively. The main clinical outcomes according to patient age (≤ 60 vs> 60 years) are shown in table 3. All-cause mortality was higher in the older group (hazard ratio [HR], 4.12, 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 1.56-10.89; P=.004), and differences persisted after adjustment (HR, 4.58, 95%CI, 1.61-13.1; P=.005). Of the 17 deaths, all were of noncardiovascular origin (cancer in 7, severe dementia in 1, car accident in 1, chronic pulmonary embolism hypertension in 1, intracerebral hemorrhage due to cerebral aneurysm in 1, suicide in 3, unknown origin in 3). A total of 4 patients experienced recurrent stroke events (0.8%) during the follow-up period, with no significant differences between groups (2.2% and 0.5% in the older and younger patient groups, respectively; HR, 5.08; 95%CI, 0.71-36.2; P=.105). All strokes were considered as non-PFO mediated (1 stroke 5 years post-PFO closure was considered as atherothrombotic in a patient with up to 4 cardiovascular risk factors; another patient had a stroke due to vertebral dissection; 1 stroke was related to a bioprosthetic aortic valve thrombosis; 1 patient had recurrent strokes without clear etiology). TIA events occurred in 12 patients (2.5%), with no differences between groups (3.3% vs 2.3% in the older and younger patient groups, respectively; HR, 1.71; 95%CI; 0.46-6.39; P=.424). In the univariate analysis, the combined endpoint of stroke or TIA tended to be higher in the older patient group (5.5% vs 2.6%; HR, 2.62; 95%CI, 0.89-7.75; P=.081), but this trend did not remain after adjustment (HR, 1.97; 95%CI, 0.59-6.56; P=.269). AF and myocardial infarction events were more likely to occur in the older group, but differences did not persist after adjustment. The Kaplan-Meier curves for the main clinical events after adjustment up to 12-year follow-up are shown in figure 1.

Long-term clinical outcomes following patent foramen ovale closure, according to patients’ age

| > 60 years(n=90) | ≤ 60 years(n=385) | HR (95%CI) | P | Adjusted HR | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 7 (7.8) | 10 (2.6) | 4.12 (1.56-10.89) | 0.004 | 4.58 (1.61-13.1) | .005 |

| Stroke | 2 (2.2) | 2 (0.5) | 5.08 (0.71-36.2) | 0.105 | 1.36 (0.14-13.4) | .791 |

| TIA | 3 (3.3) | 9 (2.3) | 1.71 (0.46-6.39) | 0.424 | 1.65 (0.40-6.91) | .495 |

| Composite of stroke and TIA | 5 (5.5) | 10 (2.6) | 2.62 (0.89-7.75) | 0.081 | 1.97 (0.59-6.56) | .269 |

| DVT/pulmonary embolism | 2 (2.2) | 6 (1.5) | 1.88 (0.37-9.39) | 0.444 | 1.26 (0.20-8.11) | .801 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 (5.5) | 7 (1.8) | 4.09 (1.28-13.16) | 0.018 | 2.26 (0.60-8.50) | .225 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (3.3) | 3 (0.8) | 5.34 (1.08-26.5) | 0.04 | 3.27 (0.55-19.7) | .195 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; HR, hazard ratio; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Values are reported as No. (%).

Kaplan-Meier estimates for clinical events at 12-year follow-up after adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics between groups. Kaplan-Meier plots showing: cumulative mortality (A), stroke (B), TIA (C), and stroke and TIA (D) at a 12-year follow-up according to age (≤ 60 years or > 60 years). 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

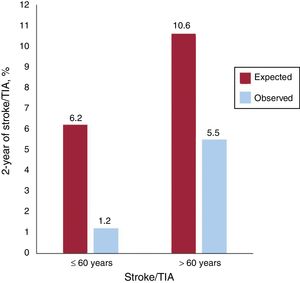

To put these results into perspective, the stroke/TIA event rate in our study population was compared with that expected according to the RoPE score20 (figure 2). According to this score, the rate of stroke/TIA at the 2-year follow-up would have been of 6.2% and 10.6% under medical therapy only, vs the observed rate of 1.2% and 5.5% in younger and older PFO closure groups, respectively (P=.001 for both).

DISCUSSIONThe main results of our study can be summarized as follows: a) older patients with cryptogenic embolism and PFO exhibited a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors; b) PFO closure was safe in older patients, with no differences in periprocedural complications compared with younger patients; c) at long-term (median of 8 years) follow-up post-PFO closure, the global mortality rate was higher among older patients, but differences were driven by noncardiovascular mortality (mainly cancer), and d) the rate of recurrent stroke/TIA was low (much lower than that predicted by the RoPE score), but there was a tendency toward a higher incidence of recurrent stroke/TIA among older patients, which appeared to be partially related to cardiovascular risk factor burden (no differences in recurrent ischemic event rate were observed after adjustment for baseline differences in cardiovascular risk factors between groups).

Several studies have shown that transcatheter PFO closure is a safe procedure in young (< 60 years) patients. However, scarce and controversial data exist on periprocedural complications in older patients. Merkler et al.21 showed a higher risk of in-hospital complications among older patients undergoing PFO closure, with a periprocedural complication rate double that observed in patients aged <60 years. In contrast, similar to the results of our study, Wahl et al.15 showed the absence of an increased periprocedural risk in older patients undergoing PFO closure. These data are reassuring and important, particularly considering the lack of randomized data and specific guideline recommendations on PFO closure in older patients.7,8

Our study is the first to provide long-term data following PFO closure in patients older than 60 years. A mean difference in age of approximately 20 years was observed between younger (< 60 years) and older patients and, not surprisingly, the long-term mortality rate among older patients was much higher than that observed in the younger population. Of note, all deaths following PFO closure were of noncardiovascular origin (with cancer as the most frequent cause of death), and the death rate observed in older patients was similar to that reported by the Institut de la Statistique du Québec for the Quebec Canadian population of the same age and sex (6.6% probability of death in the 5 years following the 65th birthday in men and 4.4% for women).22 Thus, the mortality difference observed between younger and older patients in this study seems to be driven by the higher risk of dying in older people.

The rate of recurrent thromboembolic events at long-term follow-up post-PFO closure in older patients was low, with only 2 strokes and 3 TIA episodes occurring during the follow-up period. This represents a rate of 0.3 strokes per 100 person-years and 0.8 stroke/TIA per 100 person-years, which is much lower than the incidence estimated by the RoPE score, suggesting that the beneficial effects of PFO closure may extend beyond the limit of 60 years. Previous studies have shown a low incidence of ischemic events at 1 to 3 years following PFO closure in older patients13–15 and the results of our study extend these positive findings to the long-term (> 5 years) follow-up of these patients. However, we observed a tendency toward a higher incidence of cerebrovascular events (stroke/TIA) in older (vs younger) patients. The fact that this tendency disappeared after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors suggests a potential role of atherosclerotic burden in some of the ischemic events observed in older patients.

It is well-known that the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors (particularly hypertension and diabetes) steadily increases with age, and the prevalence observed in our population of older patients is similar to that reported in the Canadian population of the same age range.23 However, the prevalence of risk factors such as dyslipidemia (35.6%), hypertension (48.9%) or diabetes (10%) was much higher than that observed in younger patients. In addition, Alsheikh-Ali et al.24 reported that in patients with cryptogenic stroke, 20% (16% to 25%) and 48% (34% to 66%) of PFOs are likely to be incidental in younger and older patients, respectively. Interestingly, these rates decrease to 9% (4% to 18%) in younger patients and to 26% (12% to 56%) in older patients when a concomitant atrial septal aneurysm is detected. This highlights the need for careful patient evaluation by an interdisciplinary team including neurologists, cardiologists, and the patient's own point of view, as described in recent guidelines.7,8 In addition, a higher incidence of AF episodes was observed among older patients in the years following PFO closure, further stressing the importance of AF screening in these patients before PFO closure. Moreover, these data raise the question about the use of longer term cardiac monitoring or even consideration of insertable cardiac monitors in some of these patients.25

The limitations of this study include those inherent to retrospective studies. Although the number of patients lost to follow-up was very low (particularly considering the long-term follow-up), we cannot completely exclude the possibility of missing some adverse events. However, this would be highly unlikely with regard to major events and those requiring rehospitalization. Also, medical records were reviewed to obtain data on patient hospitalizations over time. Finally, the referral cardiologist/neurologist, family physicians and pharmacists were also contacted if there were doubts regarding events and/or medication. The echo data were site reported and not analyzed in a central echocardiographic laboratory.

CONCLUSIONSThis study shows that PFO closure in patients older than 60 years is safe and associated with a low event rate at long-term follow-up. These results emphasize the need for the design of future randomized trials involving older patients with PFO and cryptogenic embolism. Meanwhile, this study suggests that PFO closure may be considered in older patients with cryptogenic embolism. However, the presence and number of cardiovascular risk factors favoring the atherothrombotic origin of cerebrovascular events should be taken into account in the clinical decision-making process in such patients. In addition, careful screening for arrhythmic events (particularly FA) should be undertaken in the workup before PFO closure.

FUNDINGJ. Rodés-Cabau holds the Research Chair Fondation Famille Jacques Larivière for the Development of Structural Heart Disease Interventions. J. Wintzer-Wehekind was supported by a grant from the Association de Recherche Cardio-vasculaire des Alpes”. A. Alperi and D. del Val were supported by a grant from the Fundación Alfonso Martín Escudero, Madrid, Spain.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

- –

Up to 4 recent randomized studies have established the superiority of PFO closure vs medical therapy for preventing recurrent ischemic events in patients younger than 60 years with cryptogenic stroke and PFO.

- –

Even older patients with cryptogenic stroke exhibit a much higher prevalence of PFO compared with patients with stroke of known cause.

- –

Mostly due to the lack of data, recent guidelines have excluded or failed to make strong recommendations for PFO closure in patients older than 60 years.

- –

Among patients older than 60 years, closure of PFO was safe and associated with a low rate of stroke/TIA events.

- –

Patients older than 60 years had a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors, which could lead to a higher rate of ischemic cerebral recurrences.

- –

Patients with cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale should not be excluded from PFO closure simply because of their age.