The definition of cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) has changed in recent years. At present, CTRCD is classified as mild when troponin is elevated or when there is> 15% change in global longitudinal strain (GLS) from baseline with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 50%, moderate when LVEF drops 10 points and is 40% to 49%, and severe when LVEF drops below 40%.1 The recently published Guidelines on Cardio-Oncology2 recommend starting beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) in cases of mild CTRCD to prevent progression to moderate-to-severe CTRCD, as a class IIa recommendation with level of evidence B.2

In this study, the incidence of CTRCD was measured in a cohort of patients with early HER2-positive breast cancer (eHER2-bc). Likewise, the study investigated the predictive value of high-sensitivity troponin I (hsTnI) and GLS for the appearance of moderate-to-severe CTRCD, as well as their potential as tools to aid in the decision to start cardioprotective treatment.

Between May 2018 and May 2021, 95 consecutive patients with eHER2-bc were enrolled in the study at a tertiary medical center. The exclusion criteria were baseline LVEF <50%, the presence of heart disease possibly leading to impaired LVEF during follow-up, and prior chemotherapy. Clinical and echocardiographic follow-up were performed at baseline and every 3 months until treatment completion. The biplanar Simpson method was used to analyze LVEF, and mean regional GLS was obtained by 2-, 3-, and 4-chamber analyses. Additionally, hsTnI was measured during each treatment cycle and was considered positive when above the laboratory's reference threshold (> 40 ng/L). If CTRCD was present, then cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) was also performed. Native T1- and T2-weighted values were obtained from the average value of the 16 short-axis segments in the T1- and T2-weighted mapping sequences. Extracellular volume was calculated based on the T1-weighted mapping sequences before and after contrast administration. As per protocol, treatment was started with ACEIs or beta-blockers only in cases of moderate-to-severe CTRCD.

Table 1 lists the patients’ baseline characteristics. Sequential treatment was given with anthracyclines and anti-HER2 therapy to 48.4% of patients, while anti-HER2 therapy without anthracyclines was given to the other 51.6%. During follow-up (mean, 13.6 months), symptomatic CTRCD did not appear in any patients. Nevertheless, the incidence of asymptomatic CTRCD was 60%: mild in 53 patients (55.8%), moderate in 3 (3.2%), and severe in 1 (1.1%). The mean time to CTRCD diagnosis was 162.1 days. In all, 3 patients experienced cancer progression, and 1 patient died from a noncardiovascular cause. In the bivariate analysis, cardiovascular risk factors and the use of dual anti-HER2 blockade with pertuzumab were not associated with the development of CTRCD. In the multivariate models adjusted for age, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and use of pertuzumab, the only factor associated with CTRCD was the use of anthracyclines (odds ratio=7.78; 95% confidence interval, 2.55-27.08; P <.001).

Differential characteristics of patients with eHER2-bc according to the development of CTRCD and the cancer therapy received

| Total sample (n=95) | Patients with anthracycline-based treatment (n=46) | Patients on non-anthracycline-based treatment (n=49) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CTRCD, n=38 | CTRCD, n=57 | P | No CTRCD, n=7 | CTRCD, n=39 | P | No CTRCD, n=31 | CTRCD, n=18 | P | |

| Baseline characteristics | |||||||||

| Age, y | 55.2±14.1 | 51.6±11 | .28 | 51.5±11.7 | 49.5±11.1 | .92 | 56±14.6 | 56.1±9.7 | .87 |

| Smoking | 11 (29) | 15 (26.3) | .87 | 3 (42.9) | 13 (33.3) | .75 | 8 (25.8) | 2 (11.1) | .38 |

| BMI | 25.5±5.5 | 25.7±5 | .58 | 27.1±6.5 | 24.8±3.6 | .38 | 25.2±5.3 | 27.7±6.7 | .18 |

| Hypertension | 11 (29) | 7 (12.3) | .05 | 2 (28.6) | 3 (7.7) | .15 | 9 (29) | 4 (22.2) | .75 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (13.2) | 4 (7) | .48 | 2 (28.6) | 1 (2.6) | .06 | 3 (9.7) | 3 (16.7) | .66 |

| Dyslipidemia | 9 (23.7) | 10 (17.5) | .61 | 2 (28.6) | 5 (12.8) | .57 | 7 (22.6) | 5 (27.8) | .74 |

| Baseline therapy | |||||||||

| ACEIs or ARBs | 2 (5.3) | 2 (3.5) | 1 | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 1 | 2 (6.5) | 1 (5.6) | 1 |

| Beta-blockers | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.8) | 1 | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 1 | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 1 |

| Statins | 1 (2.6) | 2 (3.5) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (3.2) | 2 (11.1) | .71 |

| Baseline echocardiographic data | |||||||||

| LV end-diastolic diameter | 42.3±4.8 | 42.9±4.6 | .52 | 42.3±3.7 | 42.1±4.9 | .98 | 42.3±5 | 44.6±3.5 | .11 |

| LV end-systolic diameter | 28.3±3.8 | 27.7±3.8 | .34 | 29.1±3.9 | 27.4±3.9 | .29 | 28.1±3.9 | 28.4±3.7 | .91 |

| Left atrium, cm2 | 16.3±3.6 | 16.5±3.3 | .82 | 16.9±2.8 | 15.9±3.2 | .34 | 15.8±3.9 | 17.7±3.1 | .18 |

| TAPSE, mm | 21.2±3.5 | 21.9±3.4 | .39 | 22.3±2.7 | 22±3.4 | .62 | 21±3.7 | 21.6±3.4 | .52 |

| Mean baseline GLS | –21.4±2.2 | –22.1±2.4 | .21 | –21.2±1.1 | –22±2.3 | .36 | –21.5±2.4 | –22.3±2.6 | .02 |

| Baseline E/e’ | 7±2.6 | 7±1.8 | .78 | 7±1.9 | 7.1±1.7 | .85 | 7±2.7 | 6.9±2.1 | .98 |

| E/e’> 15 | 1 (2.6) | 2 (3.5) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 2 (11.1) | .55 | |

| Baseline LVEF, % | 61.4±3.3 | 62.1±4 | .47 | 58.7±1.4 | 62.2±3.6 | .02 | 62±3.2 | 61.9±4.8 | .61 |

| Baseline biomarkers | |||||||||

| High-sensitivity troponin I, ng/L | 3.4±0.8 | 4.8±3.8 | .16 | 3±0 | 5±4.3 | .10 | 3.5±0.9 | 4.2±2 | .54 |

| Oncologic variables | |||||||||

| Tumor stage | .34 | .24 | .31 | ||||||

| I | 10 (26.3) | 5 (8.8) | 0 | 2 (5.1) | 10 (9.7) | 3 (16.7) | |||

| II A | 16 (42.1) | 30 (52.6) | 2 (28.6) | 21 (53.8) | 14 (29) | 9 (50) | |||

| II B | 8 (21.1) | 13 (22.8) | 1 (14.3) | 9 (23.1) | 7 (12.9) | 4 (22.2) | |||

| III A | 1 (2.6) | 4 (7) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (7.7) | 0 | 1 (5.6) | |||

| III B | 1 (2.6) | 2 (3.5) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (5.1) | 0 | 0 | |||

| III C | 2 (5.3) | 3 (5.3) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (5.1) | 0 | 1 (5.6) | |||

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||

| Anthracyclines | 7 (18.4) | 39 (68.4) | <.001 | 7 (100) | 39 (100) | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Doxorubicin | 4 (10.5) | 19 (33.3) | .02 | 4 (57.1) | 19 (48.7) | 1 | |||

| Liposomal doxorubicin | 1 (2.6) | 2 (3.5) | 1 | 1 (14.3) | 2 (5.1) | .39 | |||

| Adriamycin | 2 (5.3) | 20 (35.1) | .001 | 2 (28.6) | 20 (51.3) | .42 | |||

| Cyclophosphamide | 7 (18.4) | 39 (68.4) | <.001 | 7 (100) | 39 (100) | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Taxanes | |||||||||

| Docetaxel | 14 (36.8) | 14 (24.6) | .25 | 0 | 3 (7.7) | 1 | 14 (45.2) | 11 (61.1) | .36 |

| Paclitaxel | 24 (63.2) | 44 (77.2) | .16 | 7 (100) | 37 (94.9) | 1 | 17 (54.8) | 7 (38.9) | .37 |

| Carboplatin | 14 (36.8) | 11 (19.3) | .1 | 0 | 0 | 14 (45.2) | 11 (61.1) | .38 | |

| Pertuzumab | 26 (68.4) | 51 (89.5) | .01 | 7 (100) | 37 (94.9) | 1 | 19 (61.3) | 14 (77.8) | .35 |

| Radiotherapy | |||||||||

| Mean cardiac dose | 1.94±1.8 | 1.97±1.8 | .91 | 1.55±1 | 1.98±1.7 | .68 | 2±1.9 | 1.9±2 | .76 |

| Follow-up: biomarkers and echocardiogram | |||||||||

| High-sensitivity troponin I elevation | 0 | 37 (37.6) | 0 | 35 (89.7) | 0 | 2 (11.1) | |||

| High-sensitivity troponin I peak | 10.2±10.7 | 123.8±179.1 | <.001 | 27.3±14.7 | 139.9±132.7 | .001 | 6.5±4.5 | 84.6±261.7 | .17 |

| > 15%change in GLS | 0 | 36 (63.2) | 0 | 20 (51.3) | 0 | 16 (88.9) | |||

| Worse GLS | –20±2 | –18.7±2.1 | .002 | –20.2±1.5 | –19±1.9 | .08 | –20±2.1 | –18±2.5 | .01 |

| LVEF <50% | 0 | 4 (7) | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 3 (16.7) | |||

| Worse LVEF, % | 59.5±2.9 | 57.1±5.5 | .02 | 58.1±3.3 | 57.6±3.6 | .76 | 59.7±2.8 | 55.9±8.2 | .18 |

ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; CTRCD, cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

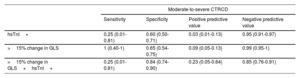

A total of 37 (38.9%) patients exhibited hsTnI elevation and 36 (37.9%) had> 15% change in GLS; 16 patients had both abnormalities. However, only 4 (4.2%) patients had moderate-to-severe CTRCD. Table 1 shows the distribution of the TnI, GLS, and LVEF abnormalities based on whether or not anthracyclines had been given. Table 2 lists the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of hsTnI and> 15% change in GLS in predicting the appearance of moderate-to-severe CTRCD. While the sensitivity, specificity, and PPV were poor for hsTnI and GLS, the NPV was 95.1% and 99%, respectively. In contrast, only 1 of 4 patients with moderate-to-severe CTRCD had hsTnI elevation, and although all also exhibited> 15% change in GLS, this change was not documented until moderate-to-severe CTRCD was diagnosed.

Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value of hsTnI and GLS for the development of moderate-to-severe CTRCD

| Moderate-to-severe CTRCD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | |

| hsTnI+ | 0.25 (0.01-0.81) | 0.60 (0.50-0.71) | 0.03 (0.01-0.13) | 0.95 (0.91-0.97) |

| >15% change in GLS | 1 (0.40-1) | 0.65 (0.54-0.75) | 0.09 (0.05-0.13) | 0.99 (0.95-1) |

| >15% change in GLS+hsTnI+ | 0.25 (0.01-0.81) | 0.84 (0.74-0.90) | 0.23 (0.05-0.64) | 0.85 (0.76-0.91) |

CTRCD, cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction; GLS, global longitudinal strain; hsTnI, high-sensitivity troponin I.

In keeping with the results of the Cardiotox registry,3 our eHER2-bc cohort also showed a high incidence of mild CTRCD in the form of increased hsTnI and abnormal GLS, whereas the incidence of moderate-to-severe CTRCD was low (4.2%). As in other series,4 the added value of hsTnI and GLS came mainly from their high NPV for predicting moderate-to-severe CTRCD, whereas the value of sensitivity, specificity, and PPV was slight. Although we consider that the presence of mild CTRCD warrants close cardiologic follow-up,5 none of the 53 patients in our series who had mild CTRCD progressed to moderate-to-severe CTRCD during follow-up despite not starting ACEI or beta-blocker therapy. On the other hand, only 1 of 4 patients with moderate-to-severe CTRCD had previously had mild CTRCD and, therefore, the other 3 would have had no indication for this treatment. Last, 38.2% of cMRIs performed on patients with mild CTRCD were entirely normal, and no abnormalities were observed in the mapping parameters of T1- or T2-weighted sequences or in extracellular volume. Although these results are limited by the small sample size, they indicate that the risk of progression to moderate-to-severe CTRCD in these patients with normal cMRI is likely low, even without cardioprotective therapy. Consequently, cMRI could be useful as an additional marker when deciding whether or not to start cardioprotective therapy in patients with mild CTRCD.

FUNDINGThis study received funding through a grant from the Spanish Society of Cardiology in 2017 and from a FIS project of the ISC-III in 2017 PI17/510.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSG. Oristrell and I. Ferreira-González have contributed to the text of the article and the statistical analyses. M. Arumí and S. Escrivá-de-Romaní have contributed in the inclusion of patients in the study. F. Valente and G. Burcet have contributed to the performance of echocardiograms and cMRIs on patients included in the study.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests regarding this project.

.