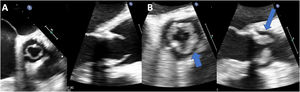

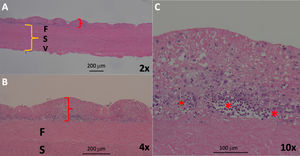

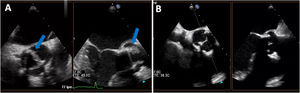

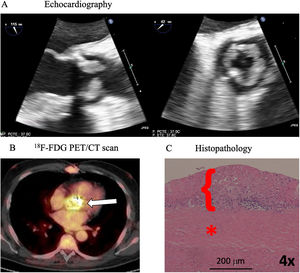

Diffuse homogeneous hypoechoic leaflet thickening, with a wavy leaflet motion documented by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), has been described in some cases of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) involving aortic bioprosthesis (AoBio-PVE). This echocardiographic finding has been termed valvulitis. We aimed to estimate the prevalence of valvulitis, precisely describe its echocardiographic characteristics, and determine their clinical significance in patients with AoBio-PVE.

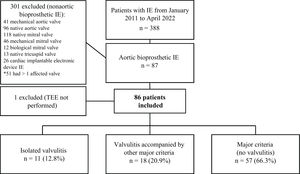

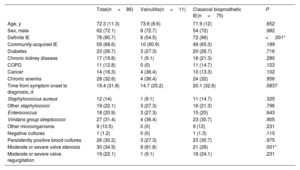

MethodsFrom 2011 to 2022, 388 consecutive patients with infective endocarditis (IE) admitted to a tertiary care hospital were prospectively included in a multipurpose database. For this study, all patients with AoBio-PVE (n=86) were selected, and their TEE images were thoroughly evaluated by 3 independent cardiologists to identify all cases of valvulitis.

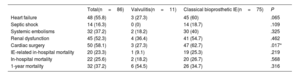

ResultsThe prevalence of isolated valvulitis was 12.8%, and 20.9% of patients had valvulitis accompanied by other classic echocardiographic findings of IE. A total of 9 out of 11 patients with isolated valvulitis had significant valve stenosis, whereas significant aortic valve regurgitation was documented in only 1 patient. Compared with the other patients with AoBio-PVE, cardiac surgery was less frequently performed in patients with isolated valvulitis (27.3% vs 62.7%, P=.017). In 4 out of 5 patients with valve stenosis who did not undergo surgery but underwent follow-up TEE, valve gradients significantly improved with appropriate antibiotic therapy.

ConclusionsValvulitis can be the only echocardiographic finding in infected AoBio and needs to be identified by imaging specialists for early diagnosis. However, this entity is a diagnostic challenge and additional imaging techniques might be required to confirm the diagnosis. Larger series are needed.

Keywords

Identify yourself

Not yet a subscriber to the journal?

Purchase access to the article

By purchasing the article, the PDF of the same can be downloaded

Price: 19,34 €

Phone for incidents

Monday to Friday from 9am to 6pm (GMT+1) except for the months of July and August, which will be from 9am to 3pm