Acute heart failure describes the rapid deterioration, over minutes, days or hours, of symptoms and signs of heart failure. Its management is an interdisciplinary challenge that requires the cooperation of various specialists. While emergency providers, (interventional) cardiologists, heart surgeons, and intensive care specialists collaborate in the initial stabilization of acute heart failure patients, the involvement of nurses, discharge managers, and general practitioners in the heart failure team may facilitate the transition from inpatient care to the outpatient setting and improve acute heart failure readmission rates. This review highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to acute heart failure with particular focus on the chain-of-care delivered by the various services within the healthcare system.

Keywords

Acute heart failure (AHF) describes the rapid onset or worsening of symptoms and signs of heart failure (HF),1 usually leading to hospitalization. It is a life-threatening condition and the most common diagnosis among patients suffering from acute respiratory distress.2,3 The term AHF is also often extended to patients with more gradual deterioration, with increasing exertional dyspnea and worsening peripheral edema and for this reason some people have coined the term “hospitalized HF” as a more accurate reflection of the clinical problem.4 Although worsening peripheral edema may appear less alarming than pulmonary edema, it may carry a worse prognosis, perhaps because it reflects biventricular rather than only left ventricular failure.5

Heart failure is common6 and there has been a steady rise in AHF admissions over the last decade.7–9 An aging population and improved survival after the onset of cardiovascular disease is expected to further increase HF incidence and prevalence.10 Most people who die of cardiovascular diseases will first develop HF.11 The management of HF is an interdisciplinary challenge that requires the cooperation of various specialists (Figure).

EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICESPatients suffering from AHF may contact emergency medical services (EMS) because of acute symptoms such as dyspnoea, syncope, palpitations, or thoracic pain. An analysis of 4083 consecutive EMS contacts in Denmark found HF to be the primary discharge diagnosis in 3.1% of these patients.12 However, AHF may also be present in patients with other primary diagnoses such as acute coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, or valvular disease. Based on physical signs and symptoms alone, the prehospital diagnosis of AHF can be challenging.13–15 Studies on the accuracy of EMS diagnosis and treatment of AHF found rates of error ranging from 9%14 to 23%.15 While EMS treatment overall seems to improve the survival of AHF patients,13,16 erroneous diagnosis and treatment may on the other hand result in increased mortality rates.16 The organization and structure of EMS vary amongst geographical regions and may include paramedics, technicians, nurses, and physicians. Therefore, studies on the performance of EMS treatment in AHF are difficult to compare. However, the interdisciplinary cooperation of EMS teams as well as a structured handover to the hospital physician is likely to be important in the emergency care of AHF. Further research is warranted to improve the prehospital management of AHF patients.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENTSEmergency providers play an important role in the management of patients with AHF, as patients commonly present to the emergency departments of local hospitals (either self-directed or via EMS). Indeed, most cases of HF are first diagnosed in hospital rather than in primary care.17 More than 80% of emergency department patients with AHF are admitted to hospital, a proportion that has remained largely unchanged over the past 5 years.8 It is crucial that emergency providers recognize the clinical presentation of AHF, as correct diagnosis is a prerequisite for successful treatment.1 Studies show that therapeutic and management decisions made by emergency providers have a direct impact on morbidity, mortality, and hospital length of stay, all of which affect health care costs.18–20 The accuracy of the diagnosis of AHF in emergency departments is reported to vary between 71%21 and 95%.22 Patients with AHF seen in high-volume emergency departments seem to have better outcomes than patients who present to low-volume emergency departments.18 On the other hand, patients with AHF may also present after admission to any hospital ward, either as a consequence of another cardiovascular problem (eg, acute coronary syndrome/arrhythmia) or because they have cardiac disease complicating a noncardiac problem (eg, patients with hip fractures are often elderly and have hypertension and/or coronary disease) or as an iatrogenic complication (eg, excessive fluid replacement on surgical wards).

HOSPITAL CARDIOLOGISTSHeart failure outcomes are better for patients when they are admitted under specialist cardiology medical staff or have specialist HF input into their care.23–26 The first days following hospital admission are a high-risk period for the patient, when the diagnosis must be clarified or revisited, reversible factors addressed, evidence-based therapies started, comorbidities treated, and the post-discharge management planned. The European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association Standards for delivering HF care guideline therefore advises that all tertiary/teaching/university hospital referral centers should have an individual with a specific interest and expertise in HF among their cardiology staff/faculty. Ideally, 25% of the cardiology staff in tertiary/teaching/university hospital referral centers should have a HF remit.27

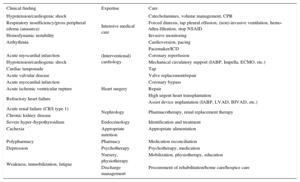

OTHER SPECIALISTSDepending on the clinical presentation of the patient and the cause for AHF, a variety of in-hospital specialists may be involved in the comprehensive care of the patient (Table).

In-hospital Specialists Involved in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Heart Failure

| Clinical finding | Expertise | Care |

|---|---|---|

| Hypotension/cardiogenic shock | Intensive medical care | Catecholamines, volume management, CPR |

| Respiratory insufficiency/gross peripheral edema (anasarca) | Forced diuresis, tap pleural effusion, (non)-invasive ventilation, hemo-/ultra-filtration, stop NSAID | |

| Hemodynamic instability | Invasive monitoring | |

| Arrhythmia | Cardioversion, pacing | |

| (Interventional) cardiology | Pacemaker/ICD | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | Coronary reperfusion | |

| Hypotension/cardiogenic shock | Mechanical circulatory support (IABP, Impella, ECMO, etc.) | |

| Cardiac tamponade | Tap | |

| Acute valvular disease | Valve replacement/repair | |

| Heart surgery | ||

| Acute myocardial infarction | Coronary bypass | |

| Acute ischemic ventricular rupture | Repair | |

| Refractory heart failure | High urgent heart transplantation | |

| Assist device implantation (IABP, LVAD, BIVAD, etc.) | ||

| Acute renal failure (CRS type 1) | Nephrology | Pharmacotherapy, renal replacement therapy |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||

| Severe hyper-/hypothyroidism | Endocrinology | Identification and treatment |

| Cachexia | Appropriate nutrition | Appropriate alimentation |

| Polypharmacy | Pharmacy | Medication reconciliation |

| Depression | Psychotherapy | Psychotherapy, medication |

| Weakness, immobilization, fatigue | Nursery, physiotherapy | Mobilization, physiotherapy, education |

| Discharge management | Procurement of rehabilitation/home care/hospice care |

BIVAD, biventricular assist device; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CRS, cardiorenal syndrome; ECMO, extracorporal membrane oxygenation; IABP, intra-aortal balloon pump; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Several transitions of care, such as emergency department to intensive care unit, intensive care unit to ward, and ward to home, often occur subsequent to discharge. These transitions are often associated with changes in the patient's medication: guideline-mandated treatments may be stopped or initiated and/or their doses or their mode of administration may be changed.28 Any breakdown in communication during these in-hospital transitions commonly reflects on medication regimens and may adversely impact patient care.29,30 Cessation or dose-reduction of guideline-indicated treatments is often intended only as a temporary measure but poor organization of care may fail to reinstate life-saving therapies after the acute problem has been solved. Transitioning between intravenous and oral diuretics also requires considerable experience. Prospective studies found that more than 50% of patients admitted to hospital had at least 1 unintended discrepancy between their chronic outpatient medication and their admission regimen.29,31 Then again, medication reconciliation performed by clinical pharmacists may improve medication adherence.32 In-hospital transitions contribute to longer lengths of stay and miscommunication. Care pathways should try to minimize the need for them. When in-hospital transitions occur, all staff involved need to communicate professionally to avoid unintentional erroneous treatment.

DISCHARGE MANAGEMENTOnce hospitalized for HF, the 30-day readmission rate approaches 25% to 50%.33 Studies investigating the determinants of HF rehospitalizations have identified comorbidities and markers of HF severity as risk factors for HF readmissions.34–36 In addition, patients with limited education and those with a foreign mother language are more likely to have poorer understanding of their condition and higher rates of 30-day readmissions.37 Hospital-based disease management programs as well as nurse-led discharge planning reduce rehospitalization rates in HF patients. Unfortunately, interventions based primarily on patient education have been shown not to reduce readmission or mortality rates.33,38–41 The National Heart Failure Audit for England and Wales enrolled more than 75 000 patients with a primary discharge diagnosis of HF. About half of patients were followed-up by a HF specialist team, which was associated with a substantially better outcome; 3-year mortality was 70% in those who did not receive specialist follow-up but only 50% in those who did.42 An analysis of the Get With The Guidelines® program including 57 969 patients hospitalized with HF between 2005 and 2010 found that referral to a HF disease management program occurred in less than one-fifth of hospitalized HF patients. Paradoxically, patients with a worse prognosis were less likely to be referred.43

Thus, increasing the availability of HF disease management programs and optimizing selection for these programs might improve the quality and effectiveness of care. A well-orchestrated team of cardiologists, general practitioners, nurses, and ancillary support staff seems important for an integrated and seamless transition from inpatient care to the outpatient setting.44

NURSING STAFFThe role of the HF specialist nurse varies depending on the regional organization of medical care. It may involve home visits, telephone contact, facilitating telemonitoring, running nurse-led clinics, participating in cardiologist-led clinics, or a combination of these, as well as providing education for health professionals involved in the management of the patient.45 The HF nursing service should function as a key link between secondary and primary care. Although the COACH study46—one of the largest randomized trials that compared disease management by a specialized HF nurse with standard follow-up by a cardiologist—did not show a reduction in the combined endpoints of death and HF hospitalization, other studies suggest that a HF nursing service may reduce morbidity and mortality.47 In 2012, a systematic review performed by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that there is good evidence that case management-type interventions led by a HF specialist nurse reduce HF-related 12-months readmissions, all-cause readmissions, and all-cause mortality in patients recently discharged after a hospital admission for HF.47

Geographical considerations and/or the needs of the patient population being cared for may make telephone-assisted management or telemonitoring a useful method to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the nursing team.27 Although outcome data for remote monitoring are conflicting, the bulk of evidence points toward a benefit of home telemonitoring on mortality and a modest effect on hospitalization in patients with a recent HF hospitalization.48,49 In contrast, well managed, stable chronic HF patients may not benefit from telemonitoring.50–52 Another large randomized trial, the BEAT-HF study,53 is ongoing. Its results may help to clarify the role of home telemonitoring in HF patients.

CARDIAC REHABILITATIONBed-rest is appropriate for the patient with pulmonary or severe peripheral edema as it conserves blood flow to essential organs, reduces cardiac work, and improves diuresis. Once the patient has been stabilized, European guidelines advise early mobilization through an individualized exercise program after hospitalization for an exacerbation of HF to prevent further disability and lay good foundations for the formal exercise training plan.54,55 In this early phase after decompensation, cardiac rehabilitation may include respiratory training, small muscle strength exercise, or simply increasing activities of daily living such as walking.54,55 Cardiac rehabilitation may also include self-care counselling that targets improved education and skill development (eg, medication compliance, monitoring/management of body weight). When clinical stabilization is achieved, exercise-based rehabilitation reduces the risk of hospital admissions and confers important improvements in health-related quality of life.56,57 As a universal agreement on exercise prescription in HF does not exist, an individualized approach is recommended, with careful clinical evaluation, including behavioral characteristics, personal goals, and preferences.54

PRIMARY CAREA robust HF management program must include the primary care physician as an important member of the multiprofessional team. Primary care physicians are often the first port of call for patients who have new or worsening symptoms/signs potentially due to HF. They play an essential role in titrating and monitoring guideline-indicated therapy and a key role in terminal care at home.27 In some countries, office-based cardiologists may also be involved in the HF team. The comanagement of HF patients by a primary care physician and a cardiologist has been shown to reduce both all-cause mortality and hospitalizations for AHF when compared with HF patients managed solely by primary care physicians.58,59 This may be explained by more effective implementation of target doses of medication and timely device implantation.60,61 Patients cared for by physicians that see only a few patients with HF may have worse outcomes,62 although this might be partly explained by differences in the sorts of patients managed by general physicians rather than cardiologists.63

PALLIATIVE CAREHeart failure guidelines indicate that palliative care should be integrated into the overall provision of care for patients with HF.1 The American Center to Advance Palliative Care defines subspecialty palliative care as follows64: “Specialized medical care for people with serious illnesses. This type of care is focused on providing patients with relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness–whatever the diagnosis or prognosis. The goal is to improve quality of life for both the patient and the family. Palliative care is delivered by a team of doctors, nurses, and other specialists who work with the patient's doctors to provide an extra layer of support”. Thus, palliative care is appropriate at any stage in a serious illness and can be provided together with curative treatment.65 Although studies show that palliative care improves quality of life and morbidity of HF patients,66–68 few patients with HF receive care from palliative care specialists.69–71 A recently published study explored barriers to palliative care referrals in HF from cardiology and primary care providers.72 Identified barriers included lack of knowledge about the field of palliative care, lack of appropriate triggers for referral, and discomfort with the term palliative care. Future work should seek to develop provider–and patient–centred interventions to reduce actionable barriers to palliative care uptake in HF.

HOSPICE CAREA hospice uses an interdisciplinary approach to deliver medical, social, physical, emotional, and spiritual services through the use of a broad spectrum of caregivers within a defined time frame at the end of life.73 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services definition of hospice is: “Care that allows the terminally ill patient to remain at home as long as possible by providing support to the patient and family and keeping the patient as comfortable as possible while maintaining his or her dignity and quality of life”.73 While hospice care was initially geared only towards the care of patients with cancer, any terminal illness with less than 6-month predicted survival currently qualifies for its institution.

Although heart disease is the leading cause of death in Western countries, there is a lingering disparity between the use of hospice and palliative services in patients with advanced HF compared with cancer. Of 58330 patients aged ≥ 65 years participating in the Get With The Guidelines® HF program, only 2.5% were discharged to a hospice.74 In 2012, only 11.4% of United States hospice patients had a primary diagnosis of heart disease.75 In addition, it was estimated that only between 11% and 39% of patients who died of advanced HF were enrolled in hospice programs.76–78 Heart failure patients entering hospice care have multiple symptoms requiring management, many of which cause considerable distress.79 Noteworthy is the finding that symptoms with the greatest reported severity were not necessarily those causing the greatest distress, as well as the relationship between symptom distress and depressive symptoms.79 Clinicians in hospices may consider specifically focusing part of their assessment and management by first addressing symptom severity and distress.

PATIENTSTreatment of HF is complex, requiring attention to diet, lifestyle, complex therapeutic regimens, and device therapy. In daily clinical life, many patients have difficulties adopting complex care regimens and adherence to evidence-based regimens remains low. Therefore, facilitating a more active role for patients in self-management of long-term medical conditions is an essential component of good clinical care. Patients may be considered the largest health care workforce available.80 There is, however, conflicting evidence as to the potential benefits of patient education and self-management on hospitalization rates and mortality.80–83 In the HART study,82 self-management counselling plus HF education did not reduce the primary endpoint of death or HF hospitalization compared with HF education alone in 902 patients with mild to moderate HF. In contrast, formal education and support intervention was shown by others81,83 to reduce adverse clinical outcomes and costs for patients with HF, while it had positive effects on quality of life, exercise capacity, and plasma concentrations of cardiac peptides.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACHCurrent HF guidelines recommend that HF patients are enrolled in a multidisciplinary-care management program to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization.1 A multidisciplinary approach to HF may reduce costs,84 decrease length of stay,85–88 curtail readmissions,86–95 improve compliance,90,96,97 and reduce mortality.91,92,94,96,98 An important limitation, however, is the substantial heterogeneity in both the terms of the models of care and the interventions offered, including: clinic or community-based systems of care, remote management, and enhanced patient self-care.27

A meta-analysis of 30 trials (7532 patients) on multidisciplinary interventions in HF found that all-cause hospital admission rates, HF admission rates and all-cause mortality were reduced by 14%, 30%, and 20%, respectively.92 The positive effects, however, varied with respect to the intervention applied: provision of home visits reduced all-cause admissions but not all-cause mortality, whereas telephone follow-up did not influence hospital admissions but reduced all-cause mortality. Hospital/clinic interventions, in contrast, had no impact on either all-cause hospitalization or all-cause mortality. Another review of 29 randomized trials (5039 patients) on multiprofessional strategies for the management of HF patients reported that follow-up by a specialized multidisciplinary team (either in a clinic or a nonclinic setting) reduced mortality, HF hospitalizations, and all-cause hospitalizations, while programs that focused on enhancing patient self-care activities reduced HF hospitalizations and all-cause hospitalizations but had no effect on mortality.94 Strategies that employed telephone contact and advised patients to attend their primary care physician in the event of deterioration reduced HF hospitalizations but not mortality or all-cause hospitalizations.

Thus, there remains considerable uncertainty about which components of multidisciplinary HF care are most important. For example, are beneficial effects mediated through more aggressive medication titration (as proposed by Mao et al91), or through enhanced surveillance? Conventional trials that randomize individual patients may not be the best way to test the effect of a service; novel approaches, such as the cluster randomized controlled trial, may be superior.49

It is unlikely that any one approach is optimal. The best form of care might seek to compensate for the weaknesses of each approach by exploiting their strengths. A strong HF cardiology lead, supported by primary care physicians, nurse specialists, and pharmacists in the hospital and community with the ability to offer patients remote support might offer the best service.

Key to the success of multidisciplinary HF programs may be the coordination of care along the spectrum of severity of HF and throughout the chain-of-care delivered by the various services within the healthcare system.1 Further research is warranted to identify the most efficacious multidisciplinary approaches to AHF.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTJ.G.F. Cleland reports research support from Amgen, Novartis, and Servier. L. Frankenstein reports research support from Roche, Novartis, and Servier.