Time between the onset of cardiorespiratory arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a key prognostic factor, with survival rates decreasing by 5% to 10% for each minute of delay.1 In out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA), immediate CPR usually depends on bystander action.2

Law enforcement agencies (LEA) have more units and are more geographically dispersed than emergency medical services. In addition, during workdays they are usually ready to act when on patrol. Consequently, they are frequently first responders in emergencies. In the United States, police or firefighters initiated CPR in 31.8% of OHCA.3 In Spain, only 24.1% of Local Police and 11.2% of Civil Guard officers had ever performed CPR in real-life situations.4 However, although CPR training is included in the training plan for LEAs in Spain, there are no regulations for periodic refresher courses. Conversely, in most high-income countries, LEAs are integrated within emergency systems and dual mobilization is encouraged. Studies have found favorable results in survival and neurological outcomes when CPR was initiated by properly trained LEA officers.3

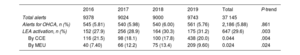

Considering these data, we were interested in determining the time trend for the rates of LEA intervention in OHCA and in estimating officers’ knowledge of this procedure and willingness to act as first responders. To achieve these objectives, we first conducted a retrospective study of activations and LEA interventions in emergencies involving OHCA from 2016 to 2019, with the permission of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Asturias (Spain). Cases of OHCA were identified using registers from the Coordinating Center for Emergencies of Asturias (Spain) and were later linked to medical records of the emergency department to determine whether LEA were simultaneously dispatched. We also classified LEA interventions according to activator. Nevertheless, limitations of the study were that the records did not allow us to determine the specific LEA activated (National Police, Local Police or Civil Guard) or identify situations where LEA officers were the first activated emergency medical units to arrive.

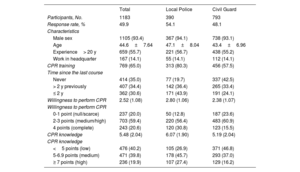

Second, we performed a cross-sectional study among Local Police and Civil Guard officers of Asturias to describe training, knowledge of CPR, and willingness to perform this procedure (2017 to 2019). All participants provided informed consent and the study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Asturias (Spain). The Local Police cover mainly urban areas whereas the Civil Guard cover rural settings. The National Police Agency was also invited as their agents are potentially first responder in urban areas, but refused to participate, which constituted another limitation. Finally, the study involved 1183 officers (67.0% from the Civil Guard). Officers were surveyed using a questionnaire that included CPR training intervals (never,> 2 years, ≤ 2 years since the last course); willingness to act in OHCA, based on responses to 4 questions (responses were summed to obtain a 4-point scale, with higher values indicating higher willingness); and knowledge of CPR, which was summarized in 9 questions based on the 2015 international recommendations for adults (responses were translated to a 10-point scale, with 10 representing highest knowledge). The questionnaire was designed by a mixed panel of experts in out-of-hospital emergencies and psychometric evaluation.4

The frequency of LEA activation in emergencies involving OHCA is shown in table 1. Although the number of OHCA alerts remained stable during the study period, there was an increasing trend in the activation of LEA agents (P trend=.003). This increase was due to increased demand from mobile emergency units, which requested support from LEAs in 5.10% of OHCAs in 2016 and 13.4% in 2019. In contrast, 35% of the LEAs had never received training and only 30.6% had been trained within the 2 years prior to the survey (table 2), which is considered the cutoff point for the minimum training intervals. In addition, the percentage of LEA officers fully willing to act as first responders and with considerable knowledge of CPR was around 20%. All indicators were worse among Civil Guard officers compared with the Local Police.

Trend in LEA intervention in emergencies with OHCA

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total | P-trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total alerts | 9378 | 9024 | 9000 | 9743 | 37 145 | |

| Alerts for OHCA, n (%) | 545 (5.81) | 540 (5.98) | 540 (6.00) | 561 (5.76) | 2,186 (5.88) | .861 |

| LEA activation, n (%) | 152 (27.9) | 256 (28.9) | 164 (30.3) | 175 (31.2) | 647 (29.6) | .003 |

| By CCE | 116 (21.5) | 98 (18.1) | 100 (17.8) | 438 (20.0) | 0.044 | .004 |

| By MEU | 40 (7.40) | 66 (12.2) | 75 (13.4) | 209 (9.60) | 0.024 | .024 |

CCE, Coordinating Center for Emergencies; LEA, low enforcement agencies; MEU, mobile emergency unit; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Training, knowledge of CPR and willingness to act among law enforcement officers

| Total | Local Police | Civil Guard | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, No. | 1183 | 390 | 793 |

| Response rate, % | 49.9 | 54.1 | 48.1 |

| Characteristics | |||

| Male sex | 1105 (93.4) | 367 (94.1) | 738 (93.1) |

| Age | 44.6±7.64 | 47.1±8.04 | 43.4±6.96 |

| Experience> 20 y | 659 (55.7) | 221 (56.7) | 438 (55.2) |

| Work in headquarter | 167 (14.1) | 55 (14.1) | 112 (14.1) |

| CPR training | 769 (65.0) | 313 (80.3) | 456 (57.5) |

| Time since the last course | |||

| Never | 414 (35.0) | 77 (19.7) | 337 (42.5) |

| > 2 y previously | 407 (34.4) | 142 (36.4) | 265 (33.4) |

| ≤ 2 y | 362 (30.6) | 171 (43.9) | 191 (24.1) |

| Willingness to perform CPR | 2.52 (1.08) | 2.80 (1.06) | 2.38 (1.07) |

| Willingness to perform CPR | |||

| 0-1 point (null/scarce) | 237 (20.0) | 50 (12.8) | 187 (23.6) |

| 2-3 points (medium/high) | 703 (59.4) | 220 (56.4) | 483 (60.9) |

| 4 points (complete) | 243 (20.6) | 120 (30.8) | 123 (15.5) |

| CPR knowledge | 5.48 (2.04) | 6.07 (1.90) | 5.19 (2.04) |

| CPR knowledge | |||

| <5 points (low) | 476 (40.2) | 105 (26.9) | 371 (46.8) |

| 5-6.9 points (medium) | 471 (39.8) | 178 (45.7) | 293 (37.0) |

| ≥ 7 points (high) | 236 (19.9) | 107 (27.4) | 129 (16.2) |

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Unless otherwise indicated, the data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

To improve survival rates, the CARES Surveillance Group has called for greater deployment of police officers as first responders. The group has also proposed investigating the potential for increasing their intervention in OHCA and identifying the factors that may impede or facilitate this implementation.3 A first step to increase the supply and use of LEA in emergencies is to increase the demand. In our time series, demand from mobile emergency unit physicians significantly increased, suggesting that the activation of officers is perceived by health care providers as an opportunity to achieve better outcomes, both for patient survival and for safety. The main strength of this proposal is related to response time, because, when LEA officers are dual dispatched, they arrive before the mobile emergency units in 30% of cases.5 Moreover, evidence from a systematic review and other subsequent primary studies suggest that time to defibrillation decreases and survival from OHCA increases when LEA officers are adequately trained in CPR and resourced.3,6 Among the most important barriers is the lack of self-efficacy of LEA officers to perform CPR, hindering their support to the medical response in OHCA. Improving self-efficacy, ie, the perceived capability that CPR skills can be performed in real situations, involves strengthening training. Consequently, officers should not only receive training in CPR at baseline when they enter the police academy, but should also undergo periodic refresher courses and, if possible, carry out joint courses with mobile emergency units to improve coordinated action. According to our previous research conducted in Spain, only the group of LEA officers who had been trained within the previous 2 years were willing to perform CPR and had adequate knowlege of the procedure.4

In summary, LEA activations in OHCA cases could be on the increase in Spain. However, there is a need to improve willingness to act and knowledge of CPR. Therefore, proper training and periodic CPR refresher courses for LEA agents is an urgent requirement. Moreover, given that in practice there is a trend toward dual dispatching of officers and health care workers, combined performance training could benefit both groups of professionals and the public at large.

FUNDINGThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll authors have made substantial contributions to the manuscript. I. Pérez-Regueiro, P. Menéndez-Angulo and A. Lana conceived and designed the study. I. Pérez-Regueiro, L. Carcedo-Argüelles, R. Guinea-Rivera and P. Menéndez-Angulo collected the data. L. Carcedo-Argüelles and A. Lana conducted the statistical analyses. I. Pérez-Regueiro and A. Lana drafted the original manuscript. L. Carcedo-Argüelles, P. Menéndez-Angulo and R. Guinea-Rivera revised the article for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version submitted to the journal. A. Lana is guarantor.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflict of interest.