In recent years, ventricular support devices have emerged as a rescue option for patients with cardiac arrest or refractory cardiogenic shock.1 Ventricular support with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) enables a less invasive percutaneous approach, biventricular support, and better tissue oxygenation; hence, it can be used as a bridge to decision for patients with severe multiorgan failure in whom a complete assessment cannot be carried out.2 The published experience with adults in Spain is scant3,4 and most of the reported cases are patients who have undergone cardiotomy.5 The lack of randomized studies, small sample sizes, and heterogeneity of the published series (most with elevated mortality2) make it difficult to precisely define the profile of the ideal patient for VA-ECMO.

Our objective was to analyze the baseline characteristics, indications, and duration of VA-ECMO in patients undergoing this procedure in our coronary unit, as well as the management and evolution of these patients during hospitalization and follow-up.

Between December 2009 and October 2012, 16 patients underwent VA-ECMO in our center. A Quadrox-D oxygenator system (Maquet; Wayne, New Jersey, United States) and a Jostra RotaFlow centrifugal pump (Maquet) were used in all patients, except for one case in which a CentriMag centrifugal pump (Thoratec; Pleasanton, California, United States) was used.

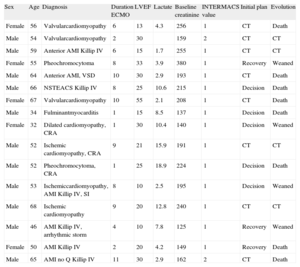

The characteristics of the patients are shown in the Table. Mean age was 54.6 years and 11 of the 16 patients (68.7%) were men. The main indication was cardiogenic shock, secondary to dilated cardiomyopathy (7/16, 43.7%), followed by myocardial infarction (6/16, 37.5%) and myocarditis (3/16, 18.7%). Four patients had experienced prolonged cardiorespiratory arrest previously.

Baseline Characteristics, Hemodynamic Status, Indications for Ventricular Support With Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, and Clinical Evolution

| Sex | Age | Diagnosis | Duration ECMO | LVEF | Lactate | Baseline creatinine | INTERMACS value | Initial plan | Evolution |

| Female | 56 | Valvularcardiomyopathy | 6 | 13 | 4.3 | 256 | 1 | CT | Death |

| Male | 54 | Valvularcardiomyopathy | 2 | 30 | 159 | 2 | CT | CT | |

| Male | 59 | Anterior AMI Killip IV | 6 | 15 | 1.7 | 255 | 1 | CT | CT |

| Female | 55 | Pheochromocytoma | 8 | 33 | 3.9 | 380 | 1 | Recovery | Weaned |

| Male | 64 | Anterior AMI, VSD | 10 | 30 | 2.9 | 193 | 1 | CT | Death |

| Male | 66 | NSTEACS Killip IV | 8 | 25 | 10.6 | 215 | 1 | Decision | Death |

| Female | 67 | Valvularcardiomyopathy | 10 | 55 | 2.1 | 208 | 1 | CT | Death |

| Male | 34 | Fulminantmyocarditis | 1 | 15 | 8.5 | 137 | 1 | Decision | Death |

| Female | 32 | Dilated cardiomyopathy, CRA | 1 | 30 | 10.4 | 140 | 1 | Decision | Weaned |

| Male | 52 | Ischemic cardiomyopathy, CRA | 9 | 21 | 15.9 | 191 | 1 | CT | CT |

| Male | 52 | Pheochromocytoma, CRA | 1 | 25 | 18.9 | 224 | 1 | Decision | Death |

| Male | 53 | Ischemiccardiomyopathy, AMI Killip IV, SI | 8 | 10 | 2.5 | 195 | 1 | Decision | Weaned |

| Male | 68 | Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 9 | 20 | 12.8 | 240 | 1 | CT | CT |

| Male | 46 | AMI Killip IV, arrhythmic storm | 4 | 10 | 7.8 | 125 | 1 | Recovery | Weaned |

| Female | 50 | AMI Killip IV | 2 | 20 | 4.2 | 149 | 1 | Recovery | Death |

| Male | 65 | AMI no Q Killip IV | 11 | 30 | 2.9 | 162 | 2 | CT | Death |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CRA, cardiorespiratory arrest; CT, cardiac transplant; ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEACS, non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome; SI, surgical intervention; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

Most of the patients (14/16, 87.5%) were in catastrophic hemodynamic collapse when admitted (INTERMACS6 category 1), despite maximum inotropic and vasoconstrictor treatment.

Half the cases were referred from third-level centers that did not have a cardiac transplantation unit. All patients required invasive mechanical ventilation. A Swan-Ganz catheter was used in 68.8% of the patients, intra-aortic counterpulsation in 75%, and renal replacement therapy in 31%.

In 50% of cases, a bridge to cardiac transplantation was initially contemplated, in 18.7%, a bridge to possible recovery, and in the remaining 31.3% a bridge to decision, pending the clinical evolution.

Nine of the 16 patients presented clinically relevant hemorrhage (hemodynamic deterioration, intervention required, or life-threatening) and 9 patients developed infections that required intravenous antibiotic therapy.

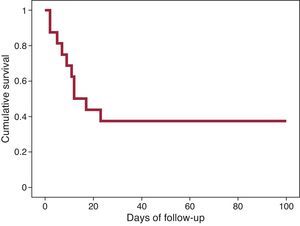

Successful weaning from VA-ECMO was achieved in 4 (25%) cases, and heart transplantation was performed in 4 others (25%). The remaining 8 patients died during VA-ECMO support. In 2 patients who achieved a degree of stability, VA-ECMO was changed to a CentriMag central biventricular assist device of medium-term duration (“bridge-to-bridge” strategy). One transplant recipient died of infection, and one patient moved to medium-term assistance died while receiving this support. In-hospital mortality was 62.5%. The progression of mortality is shown in the Figure. The main cause of death was sepsis (5/10, 50%), followed by hemorrhage (4/10, 40%) and refractory lactic acidosis, secondary to prolonged arrest in the remaining case. The 6 patients surviving hospitalization were alive at the last follow-up (mean, 441 days).

Our results show elevated mortality, which is in keeping with the rates reported in most published series.2 In light of the extreme severity of the patients’ condition and the fact that this was our initial experience, the results can be considered reasonable. The documented requirement for invasive procedures and complication rates make proper case selection especially important. It is recommended to reserve this technique for potential heart transplant candidates or cases of potentially reversible acute heart disease in patients younger than 70 years.

The main limitation of this study is that it is a single-center registry with a small number of patients. We would like to highlight the importance of creating a systematic multicenter registry of cases in the future, which would provide a larger sample size and more effective use of the data.

In conclusion, the use of VA-ECMO led to rescue of 38% of patients in catastrophic hemodynamic collapse without other therapeutic options. We believe that the introduction of VA-ECMO in coronary units with a sufficient volume of highly complex patients would be a notable step ahead in the management of critically ill patients with advanced heart failure.Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Nicolás Manito for his valuable supervision and critical review of the article.

.