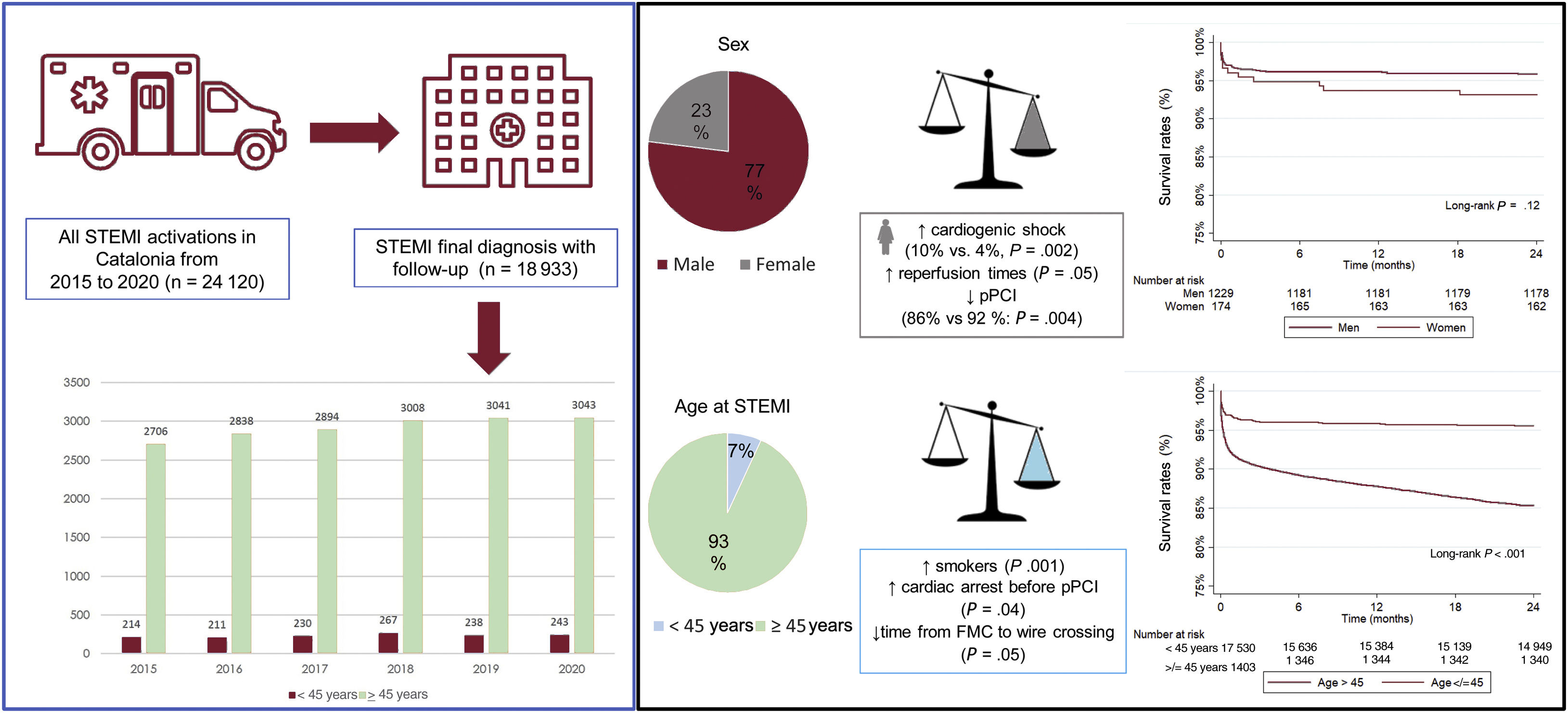

Data on the clinical profile and outcomes of younger patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is scarce. This study compared clinical characteristics and outcomes between patients aged<45 years and those aged ≥ 45 years with STEMI managed by the acute myocardial infarction code (AMI Code) network. Sex-based differences in the younger cohort were also analyzed.

MethodsThis multicenter study collected individual data from the Catalonian AMI Code network. Between 2015 and 2020, we enrolled patients with an admission diagnosis of STEMI. Primary endpoints were all-cause mortality within 30 days, 1 year, and 2 years.

ResultsOverall, 18 933 patients (23% female) were enrolled. Of them, 1403 participants (7.4%) were aged<45 years. Younger patients with STEMI were more frequently smokers (P<.001) and presented with cardiac arrest and TIMI flow 0 before pPCI (P<.05), but the time from first medical contact to wire crossing was shorter than in the older group (P<.05). All-cause mortality rates were lower in patients aged<45 years (P<.001). Among younger patients, cardiogenic shock was most prevalent in women than in their male counterparts (P=.002), with the time from symptom onset to reperfusion being longer (P<.05). Compared with men aged<45 years, younger women were less likely to undergo pPCI (P=.004).

ConclusionsDespite showing high-risk features on admission, young patients exhibit better outcomes than older patients. Differences in ischemia times and treatment were observed between men and women.

Keywords

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common cause of death worldwide. Although the overall incidence of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) has decreased in developed countries in the last decade, data from several registries have shown that this trend is not equal for all age subgroups, with a stable, even increasing, incidence of ACS being observed in younger patients.1 So far, there has been no standard definition of “young” age in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Several cutoff points appear throughout the literature, with the age of ≤ 45 years being the most consistent.2–4 Moreover, it has been reported that 4% to 10% of AMIs occur before the age of 45 years, while the incidence declines if the age limit is lower.4

Cardiovascular risk factors and clinical presentation differ in older compared with younger patients. The most frequent initial manifestation in the latter is ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).5 Sex differences and predictors of mortality have been described in small cohorts of young patients with ACS.6 The young population with ACS, especially women, has been underrepresented in many clinical trials due to their lower incidence of ACS.7 Considering the above, it is essential to have more data on younger patients presenting with STEMI. Clinical STEMI guidelines recommend regional STEMI networks to organize all key stakeholders so that patients can receive optimal and timely reperfusion treatment (primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI), fibrinolysis, or a combination of both).8

Using the database from the Catalonia AMI Code network registry (Codi IAM), this study aimed to analyze and compare clinical characteristics, in-hospital and 2-year outcomes between patients aged<45 years and those aged ≥ 45 years. Given the relevance of a sex bias in diagnosis and the prognostic implications after an ACS in women, we also analyzed sex-based differences in patient characteristics and prognosis.

METHODSPatient selection and follow-upThis observational multicenter retrospective study included all consecutive patients from the registry of the AMI Code diagnosed with STEMI between 2015 and 2020. We excluded patients with a diagnosis different than STEMI (for example, pericarditis, myopericarditis, etc). The flowchart of the study is presented in .

The AMI Code network was launched in 2010 in a region of 7.6 million inhabitants. Ten pPCI hospitals are open 24hours a day, 7 days a week. Updated operating details of the network have been recently published.9 An emergency medical service (EMS) is responsible for coordinating the detection of patients with STEMI and transfer to pPCI hospitals (via EMS ambulances and helicopters). The AMI Code registry includes demographic, clinical, therapeutic, and discharge data collected electronically from patients with STEMI within the previous 12hours. Patient mortality data were obtained from the National Mortality Registry. The quality of the data included in the registry are periodically verified by external audits. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of all participating centers and complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study endpoints and definitionsStandardized definitions of all patient-related variables, clinical diagnoses, and hospital complications and outcomes were used. All patients admitted with an ACS were classified as STEMI according to current clinical practice guidelines10 and the fourth definition of AMI.11 Epicardial coronary flow in the STEMI culprit artery was graded according to the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade,12 and reperfusion was considered optimal when TIMI 3 flow was obtained at the culprit lesion in less than 120minutes from the first medical contact.

The primary assessment endpoints were all-cause mortality within 30 days, 1 year, and 2 years.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages), assessing the differences by the chi-square test (or Fisher test when necessary). Continuous variables are presented as mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to ensure normal distribution. Continuous variables were compared using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or the Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. Survival curves using all available follow-up data were constructed for the time-to-event variables using the Kaplan-Meier method. For all analyses, a 2-tailed P value<.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance. Follow-up was considered to terminate at the date of the last follow-up. Analyses were performed using STATA software (V 14.0, StataCorp LP, United States).

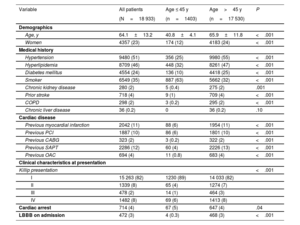

RESULTSRegistry populationA total of 18 933 patients (23% female) with an admission diagnosis of STEMI were enrolled in the AMI Code registry between January 2015 and December 2020. Of them, 1403 participants (7.4%) were aged<45 years. The proportion of women was higher in the older age group (P<.001). The main baseline characteristics and clinical presentation of the 2 groups are summarized in table 1. A higher proportion of patients younger than 45 years were smokers (P<.001). In contrast, patients>45 years had a higher prevalence of the other common risk factors (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes) and other comorbidities (chronic kidney disease, previous cardiovascular events, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic liver disease).

Clinical characteristics

| Variable | All patients | Age ≤ 45 y | Age>45 y | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=18 933) | (n=1403) | (n=17 530) | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 64.1±13.2 | 40.8±4.1 | 65.9±11.8 | <.001 |

| Women | 4357 (23) | 174 (12) | 4183 (24) | <.001 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 9480 (51) | 356 (25) | 9980 (55) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8709 (46) | 448 (32) | 8261 (47) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4554 (24) | 136 (10) | 4418 (25) | <.001 |

| Smoker | 6549 (35) | 887 (63) | 5662 (32) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 280 (2) | 5 (0.4) | 275 (2) | .001 |

| Prior stroke | 718 (4) | 9 (1) | 709 (4) | <.001 |

| COPD | 298 (2) | 3 (0.2) | 295 (2) | <.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 36 (0.2) | 0 | 36 (0.2) | .10 |

| Cardiac disease | ||||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 2042 (11) | 88 (6) | 1954 (11) | <.001 |

| Previous PCI | 1887 (10) | 86 (6) | 1801 (10) | <.001 |

| Previous CABG | 323 (2) | 3 (0.2) | 322 (2) | <.001 |

| Previous SAPT | 2286 (12) | 60 (4) | 2226 (13) | <.001 |

| Previous OAC | 694 (4) | 11 (0.8) | 683 (4) | <.001 |

| Clinical characteristics at presentation | ||||

| Killip presentation | <.001 | |||

| I | 15 263 (82) | 1230 (89) | 14 033 (82) | |

| II | 1339 (8) | 65 (4) | 1274 (7) | |

| III | 478 (2) | 14 (1) | 464 (3) | |

| IV | 1482 (8) | 69 (6) | 1413 (8) | |

| Cardiac arrest | 714 (4) | 67 (5) | 647 (4) | .04 |

| LBBB on admission | 472 (3) | 4 (0.3) | 468 (3) | <.001 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LBBB, left brunch bundle block; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; OAC, oral anticoagulation; SAPT, single antiplatelet therapy.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

In the cohort of patients aged<45 years, 111 patients were aged<35 years. The proportion of smokers in this group was even higher. The specific baseline characteristics and clinical presentation of patients aged<35 years are shown in .

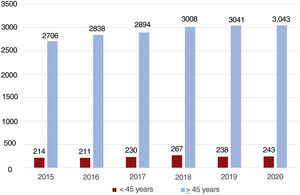

Younger patients were more frequently in Killip class I than older patients (P<.001). In contrast, cardiac arrest on presentation was more frequent in participants aged<45 years than in older patients (P=.04). The number of STEMI patients during these 6 years (2015-2020) remained stable even in 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic occurred (figure 1).

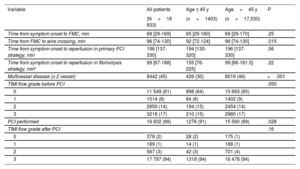

There were no significant differences between symptom onset and first medical contact (FMC) between both groups, but pPCI was more frequently performed in younger patients (P=.028). Compared with older patients, younger patients tended to have a higher rate of TIMI flow 0 before PCI (P=.05), but the time from FMC to wire crossing was shorter in younger patients [92 (72-124) vs 96 (74-130); P=.015]. The postprocedural TIMI flow 3-grade rate was similar in the 2 groups. Table 2 summarizes the times of intervention and procedural characteristics of both groups.

Time of intervention and procedural characteristics

| Variable | All patients | Age ≤ 45 y | Age>45 y | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=18 933) | (n=1403) | (n=17,530) | ||

| Time from symptom onset to FMC, min | 69 [29-169] | 65 [29-160] | 69 [29-170] | .25 |

| Time from FMC to wire crossing, min | 96 [74-130] | 92 [72-124] | 96 [74-130] | .015 |

| Time from symptom onset to reperfusion in primary PCI strategy, min | 196 [137-330] | 194 [130-320] | 196 [137-330] | .06 |

| Time from symptom onset to reperfusion in fibrinolysis strategy, min* | 99 [67-188] | 155 [76-225] | 99 [66-181.5] | .22 |

| Multivessel disease (≥ 2 vessel) | 8442 (45) | 426 (30) | 8016 (46) | <.001 |

| TIMI flow grade before PCI | .050 | |||

| 0 | 11 549 (61) | 898 (64) | 10 693 (60) | |

| 1 | 1514 (8) | 84 (6) | 1402 (9) | |

| 2 | 2650 (14) | 194 (15) | 2454 (14) | |

| 3 | 3218 (17) | 210 (15) | 2980 (17) | |

| PCI performed | 16 832 (89) | 1276 (91) | 15 560 (89) | .028 |

| TIMI flow grade after PCI | .16 | |||

| 0 | 378 (2) | 28 (2) | 175 (1) | |

| 1 | 189 (1) | 14 (1) | 168 (1) | |

| 2 | 567 (3) | 42 (3) | 701 (4) | |

| 3 | 17 797 (94) | 1318 (94) | 16 478 (94) |

FMC, first medical contact; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range].

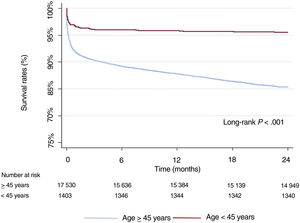

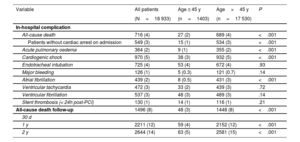

At the 2-year follow-up, 2644 patients had died (14%). Compared with older patients, younger patients showed lower rates of all-cause mortality, both in-hospital and at 1 and 2 years (P<.001). Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in figure 2. Younger patients also had fewer complications after hospital admission, such as heart failure, cardiogenic shock, and atrial fibrillation. As inpatients, no differences were observed in bleeding complications, ventricular arrhythmias, or acute stent thrombosis. A comparison of clinical outcomes between younger and older patients is presented in table 3.

Clinical outcomes

| Variable | All patients | Age ≤ 45 y | Age>45 y | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=18 933) | (n=1403) | (n=17 530) | ||

| In-hospital complication | ||||

| All-cause death | 716 (4) | 27 (2) | 689 (4) | <.001 |

| Patients without cardiac arrest on admission | 549 (3) | 15 (1) | 534 (3) | <.001 |

| Acute pulmonary oedema | 364 (2) | 9 (1) | 355 (2) | <.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 970 (5) | 38 (3) | 932 (5) | <.001 |

| Endotracheal intubation | 725 (4) | 53 (4) | 672 (4) | .93 |

| Major bleeding | 126 (1) | 5 (0.3) | 121 (0.7) | .14 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 439 (2) | 8 (0.5) | 431 (3) | <.001 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 472 (3) | 33 (2) | 439 (3) | .72 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 537 (3) | 48 (3) | 489 (3) | .14 |

| Stent thrombosis (< 24h post-PCI) | 130 (1) | 14 (1) | 116 (1) | .21 |

| All-cause death follow-up | 1496 (8) | 48 (3) | 1448 (8) | <.001 |

| 30 d | ||||

| 1 y | 2211 (12) | 59 (4) | 2152 (12) | <.001 |

| 2 y | 2644 (14) | 63 (5) | 2581 (15) | <.001 |

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

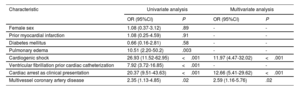

After multivariate analysis, Killip grade IV, cardiac arrest at admission, and multivessel CAD were independent predictors of in-hospital death in patients aged<45 years. Table 4 shows the independent predictors of in-hospital mortality among younger patients.

Predictors of in-hospital death according to characteristics at admission in younger patients

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Female sex | 1.08 (0.37-3.12) | .89 | - | - |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1.08 (0.25-4.59) | .91 | - | - |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.66 (0.16-2.81) | .58 | - | - |

| Pulmonary edema | 10.51 (2.20-50.2) | .003 | - | - |

| Cardiogenic shock | 26.93 (11.52-62.95) | <.001 | 11.97 (4.47-32.02) | <.001 |

| Ventricular fibrillation prior cardiac catheterization | 7.92 (3.72-16.85) | <.001 | - | - |

| Cardiac arrest as clinical presentation | 20.37 (9.51-43.63) | <.001 | 12.66 (5.41-29.62) | <.001 |

| Multivessel coronary artery disease | 2.35 (1.13-4.85) | .02 | 2.59 (1.16-5.76) | .02 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Of the 1403 patients aged<45, a total of 174 (12%) were women. Compared with their male counterparts, younger women were less likely to be current smokers (56% vs 64%; P=.02). Among patients aged<45 years, no significant differences in the prevalence of modifiable cardiovascular risks factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes were found between men and women. The baseline characteristics of younger patients stratified by sex are presented in table 5.

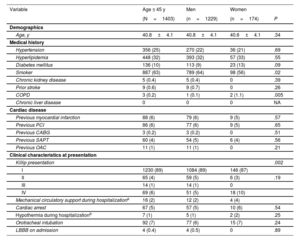

Baseline characteristics of younger patients stratified by sex

| Variable | Age ≤ 45 y | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=1403) | (n=1229) | (n=174) | P | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 40.8±4.1 | 40.8±4.1 | 40.6±4.1 | .34 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 356 (25) | 270 (22) | 36 (21) | .69 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 448 (32) | 393 (32) | 57 (33) | .55 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 136 (10) | 113 (9) | 23 (13) | .09 |

| Smoker | 887 (63) | 789 (64) | 98 (56) | .02 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (0.4) | 5 (0.4) | 0 | .39 |

| Prior stroke | 9 (0.6) | 9 (0.7) | 0 | .26 |

| COPD | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (1.1) | .005 |

| Chronic liver disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Cardiac disease | ||||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 88 (6) | 79 (6) | 9 (5) | .57 |

| Previous PCI | 86 (6) | 77 (6) | 9 (5) | .65 |

| Previous CABG | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 | .51 |

| Previous SAPT | 60 (4) | 54 (5) | 6 (4) | .56 |

| Previous OAC | 11 (1) | 11 (1) | 0 | .21 |

| Clinical characteristics at presentation | ||||

| Killip presentation | .002 | |||

| I | 1230 (89) | 1084 (89) | 146 (87) | |

| II | 65 (4) | 59 (5) | 6 (3) | .19 |

| III | 14 (1) | 14 (1) | 0 | |

| IV | 69 (6) | 51 (5) | 18 (10) | |

| Mechanical circulatory support during hospitalizationa | 16 (2) | 12 (2) | 4 (4) | |

| Cardiac arrest | 67 (5) | 57 (5) | 10 (6) | .54 |

| Hypothermia during hospitalizationb | 7 (1) | 5 (1) | 2 (2) | .25 |

| Orotracheal intubation | 92 (7) | 77 (6) | 15 (7) | .24 |

| LBBB on admission | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 0 | .89 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NA, not applicable; OAC, oral anticoagulation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SAPT, single antiplatelet therapy.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

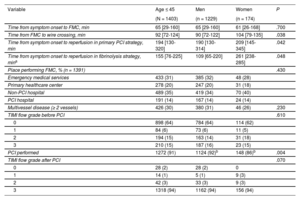

The rate of cardiogenic shock as a complication of STEMI at initial presentation was most prevalent in younger women than in men (10% vs 5%; P=.002). Although there were no significant differences in the time from symptom onset to FMC in either group, the time from symptom onset to myocardial reperfusion, independently of the therapeutic strategy used, was longer in younger women than in their male counterparts (209 [145-345] minutes vs 190 [130-314] minutes; P=.042 in pPCI; and 261 [238-285] minutes vs 109 [65-220] minutes; P=.048 in fibrinolysis strategy, respectively]. Compared with men aged<45 years, younger women were less likely to undergo pPCI (86% vs 92%; P=.004). In addition, women had higher rates of endotracheal intubation during hospital admission than men (7% vs 3%; P=.006). Table 6 shows the intervention times and procedural characteristics of men and women younger than 45 years.

Time of intervention and procedural characteristics between men and women aged ≤ 45 years

| Variable | Age ≤ 45 | Men | Women | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 1403) | (n = 1229) | (n = 174) | ||

| Time from symptom onset to FMC, min | 65 [29-160] | 65 [29-160] | 61 [26-168] | .700 |

| Time from FMC to wire crossing, min | 92 [72-124] | 90 [72-122] | 104 [79-135] | .038 |

| Time from symptom onset to reperfusion in primary PCI strategy, min | 194 [130-320] | 190 [130-314] | 209 [145-345] | .042 |

| Time from symptom onset to reperfusion in fibrinolysis strategy, mina | 155 [76-225] | 109 [65-220] | 261 [238-285] | .048 |

| Place performing FMC, % (n = 1391) | .430 | |||

| Emergency medical services | 433 (31) | 385 (32) | 48 (28) | |

| Primary healthcare center | 278 (20) | 247 (20) | 31 (18) | |

| Non-PCI hospital | 489 (35) | 419 (34) | 70 (40) | |

| PCI hospital | 191 (14) | 167 (14) | 24 (14) | |

| Multivessel disease (≥ 2 vessels) | 426 (30) | 380 (31) | 46 (26) | .230 |

| TIMI flow grade before PCI | .610 | |||

| 0 | 898 (64) | 784 (64) | 114 (62) | |

| 1 | 84 (6) | 73 (6) | 11 (5) | |

| 2 | 194 (15) | 163 (14) | 31 (18) | |

| 3 | 210 (15) | 187 (16) | 23 (15) | |

| PCI performed | 1272 (91) | 1124 (92)b | 148 (86)b | .004 |

| TIMI flow grade after PCI | .070 | |||

| 0 | 28 (2) | 28 (2) | 0 | |

| 1 | 14 (1) | 5 (1) | 9 (3) | |

| 2 | 42 (3) | 33 (3) | 9 (3) | |

| 3 | 1318 (94) | 1162 (94) | 156 (94) |

FMC, first medical contact; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SCAD, spontaneous coronary artery dissection; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range].

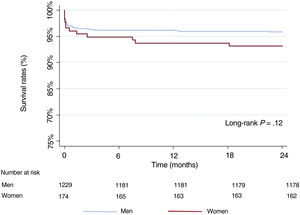

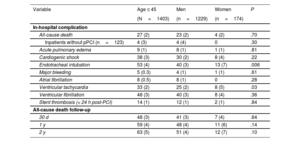

Sex-stratified clinical outcomes in the younger cohort are presented in table 7. At the 2-year follow-up, 63 patients<45 years had died (5%). Overall mortality rates in men and women were similar both in-hospital and at the 2-year follow-up (2% vs 2%; P=.70 and 4% vs 7%; P=.10, respectively). Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in figure 3.

Clinical outcomes stratified by sex in younger patients

| Variable | Age ≤ 45 | Men | Women | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=1403) | (n=1229) | (n=174) | ||

| In-hospital complication | ||||

| All-cause death | 27 (2) | 23 (2) | 4 (2) | .70 |

| Inpatients without pPCI (n=123) | 4 (3) | 4 (4) | 0 | .30 |

| Acute pulmonary edema | 9 (1) | 8 (1) | 1 (1) | .81 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 38 (3) | 30 (2) | 8 (4) | .22 |

| Endotracheal intubation | 53 (4) | 40 (3) | 13 (7) | .006 |

| Major bleeding | 5 (0.3) | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | .61 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 8 (0.5) | 8 (1) | 0 | .28 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 33 (2) | 25 (2) | 8 (5) | .03 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 48 (3) | 40 (3) | 8 (4) | .36 |

| Stent thrombosis (< 24 h post-PCI) | 14 (1) | 12 (1) | 2 (1) | .84 |

| All-cause death follow-up | ||||

| 30 d | 48 (3) | 41 (3) | 7 (4) | .64 |

| 1 y | 59 (4) | 48 (4) | 11 (6) | .14 |

| 2 y | 63 (5) | 51 (4) | 12 (7) | .10 |

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Values are expressed as No. (%).

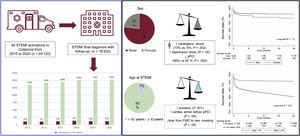

The key findings of the present study, comparing clinical characteristics, in-hospital and 1- and 2-year outcomes between patients aged<45 and ≥ 45 years, were as follows: a) younger patients with STEMI were more frequently smokers but had a lower disease burden than older patients; b) younger patients with STEMI were more likely to present with cardiac arrest, but the time frame from FMC to wire crossing was shorter than that in the older group; c) all-cause mortality rates, both in-hospital and at 2 years, were lower in patients aged<45 years; and d) despite recent advancements in STEMI treatments, a significant sex gap was noted in this study. Among patients aged<45 years, the time from symptom onset to reperfusion was longer in younger women than in their male counterparts, and they also received less primary PCI. Additionally, the rate of cardiogenic shock as a complication of STEMI at the initial presentation was more prevalent in younger women than in their male counterparts. The main findings are summarized in figure 4.

Central Illustration. Summary of the main findings of this study. Clinical profile and prognosis of young patients vs older patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction managed by the emergency-intervention AMI Code Network from 2015 to 2020 in Catalonia, Spain. Despite having high-risk features on admission, patients aged<45 years with STEMI had better outcomes than those aged>45 years. Regarding sex differences among younger patients, women had a higher prevalence of cardiogenic shock, significantly longer times from symptom onset to reperfusion, and were less likely to undergo pPCI than men. FMC, first medical contact; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

In keeping with the findings of others, at least 1 modifiable cardiovascular risk factor, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, or smoking, was identified in our cohort of patients with premature MI.13,14 In the cohort aged between 35 and 45 years, 1 in 2 patients was an active smoker, increasing to 2 in 3 patients in those aged<35 years. Many studies have analyzed the effect of different cardiovascular risk factors on the pattern and severity of CAD. Of these, the most important was smoking.15–17 Additionally, an association has been established between active and passive smoking and the development of premature CAD.18,19 Smoking accelerates atherosclerosis by increasing the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein and damaging coronary endothelial vasodilation.20 These deleterious changes result in a larger MI size, poor recovery from myocardial injury, and persistent inflammation triggering coronary recurrences, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality.21 Furthermore, inadequate control of cardiovascular risk factors is associated with decreased life expectancy and productivity costs, especially in the younger population.22 Primary and secondary prevention strategies are needed that include education targeting active smoking and lifestyle modification, especially in patients aged<45 years. Evidence demonstrates that smoking cessation is the single most effective intervention for improving long-term outcomes in younger patients, reducing all-cause and cardiovascular mortality by>50%.5 Additionally, a public health policy that embraces zero tolerance of childhood passive tobacco exposure should be pursued as there is sufficient evidence to date demonstrating the detrimental cardiovascular consequences in this group.18

In our cohort, younger patients with STEMI were more likely to have a cardiac arrest on presentation than older patients. Most ventricular fibrillation (VF) and sudden cardiac arrest are thought to occur in asymptomatic individuals without a pre-existing structural cardiac disease and represent the first manifestation of CAD. The GEVAMI study compared the first STEMI with and without VF and identified several independent risk factors for VF, including younger age.23 This finding could also be related to a higher thrombus burden in this cohort with TIMI flow 0 before pPCI. A possible explanation for this result is likely related to plaque rupture, increased blood coagulability, and greater platelet reactivity with a high propensity for thrombus formation rather than a gradual process, such as atherosclerosis in younger smokers.24 In addition, cocaine and other illicit drug use has been reported in 10% of younger patients with an AMI and associated with cardiac arrest at presentation.25

Current and previous studies have shown that young patients had a better prognosis with lower in-hospital and long-term all-cause death rates than older patients.26,27 In several studies, in-hospital mortality in younger patients with MI ranged from 0% to 4%.28–30 We observed a similar rate of all-cause mortality during hospitalization in our study. This could partially be explained by the fact that younger patients more frequently underwent pPCI and had fewer complications during hospital admission than older patients. In addition, in the present registry, there were no significant differences in major bleeding rates between older and younger patients. This absence of statistical significance could be related to a meager rate of major bleeding in the younger.

In the present study, younger patients also had better long-term outcomes after MI, with a low rate (5%) of all-cause mortality at the 2-year follow-up. This finding highlights the relevance of prompt coronary reperfusion and adequate in-hospital treatment in this group. Although there were no significant differences in the time from symptom onset to myocardial reperfusion, independently of the therapeutic strategy undertaken in younger and older patients, the time from symptom onset to reperfusion with the fibrinolysis strategy was numerically longer in the younger group. This discrepancy could be attributed to the preliminary care received in a rural outpatient clinic and the need to transfer the patient to a health care facility to administer thrombolysis. Additionally, time to diagnosis in young patients was more delayed due to diagnostic doubts in more remote primary care areas, which are less accustomed to diagnosing MI.

We found a significant sex gap regarding symptom onset to reperfusion strategy. Among patients aged<45 years, women underwent fewer pPCI than their male counterparts and had higher rates of cardiogenic shock as a complication of STEMI in the initial presentation. This has been extensively analyzed in previous studies and is attributable to many clinical, social, and economic factors. Among them is a misperception that young women are protected against cardiovascular disease, and misinterpretation of clinical symptoms leads to underestimation of cardiac disease risk with critical prognostic implications31 and reduced or delayed access to invasive treatment strategies. Given the lower proportion of women with STEMI, they are also underrepresented in clinical trials.32 Although many women will experience obstructive CAD, other diseases, such as nonobstructive coronary artery disease, spontaneous coronary artery dissection, and coronary vasospasm, are more frequent in women than in men.33 Spontaneous coronary artery dissection is an increasingly recognized cause of AMI, especially in young and middle-aged women. A conservative treatment strategy is recommended in such cases, leading to lower revascularization rates, particularly among younger women.33,34 In our cohort, 11 patients ≤ 45 years were diagnosed with spontaneous coronary artery dissection and did not receive pPCI, which could partially explain the lower revascularization rates primarily seen in younger women.

Despite growing efforts to study cardiovascular disease in women and improve educational and public awareness, a sex disparity in cardiovascular care persists across all age ranges.35,36 Measures to improve the sex gap in AMI diagnosis and access to treatments in women, especially younger women, should be emphasized and improved.

LimitationsThis registry did not collect information on family history of CAD, use of illicit drugs, lipid profile values at admission and follow-up, treatment administered during admission or upon discharge, and nonobstructive CAD (for example, vasospasm). Additionally, the registry recently incorporated details related to therapeutic hypothermia and mechanical support in 2018.

Clinical implicationsEmpowering younger patients to learn and be more actively involved in cardiovascular risk factor prevention, like smoking cessation and awareness of cardiovascular diseases, including ACS, is imperative to prevent and improve clinical outcomes. Additionally, health providers must be competent to mitigate sex disparities and provide accurate diagnosis and treatment in younger women presenting with cardiovascular disease.

CONCLUSIONSDespite showing high-risk features on admission, younger (< 45 years) patients with STEMI have better outcomes than their older counterparts. Differences in ischemia times due to the health system and treatment have been observed between men and women.

- -

The incidence of ACS is a stable, or even increasing, in younger patients (≤ 45 years).

- -

Data on the clinical profile and outcomes of younger patients with STEMI is scarce.

- -

Despite having high-risk features on admission, young (< 45 years) patients with STEMI had better outcomes than their older counterparts.

- -

Ischemia times and treatment differed between men and women. Health providers must be competent to mitigate sex disparities and provide accurate diagnosis and treatment in younger women presenting with cardiovascular disease.

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONM. Roqué and E. Flores-Umanzor conceived and designed the analysis. E. Flores-Umanzor and P.L. Cepas-Guillen performed the analysis. X. Freixa, A. Regueiro, S. Brugaletta, M. Calvo, I. Forado, M. Sabaté, M. Masotti, H. Tizón-Marcos, A. Ariza, X. Carrillo, S. Rojas, J. Muñoz, J. García, R.M. Lidón and M. Roqué reviewed and edited the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2023.03.008